Current carbon cycle models may underestimate the amount of carbon dioxide released from the soil during rainy seasons in temperate forests like those found in the northeast United States, according to Penn State researchers. Tree roots and microbes use oxygen to convert organic carbon in the soil to carbon dioxide (CO2) for energy through a process called aerobic respiration.

This release of CO2 from soils to the atmosphere represents the largest flux of carbon from terrestrial ecosystems, making it a key component of the global carbon budget. Aerobic respiration is the dominant process contributing to this flux, but the researchers found that under wet conditions, anaerobic respiration — or respiration without oxygen — also significantly contributes to the flux. Caitlin Hodges, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, said:

“In current models, amounts of carbon dioxide and oxygen are controlled by the consumption of oxygen and the production of carbon dioxide through aerobic respiration.

“It’s usually a one-to-one relationship of consumption and production. But we found that, especially in summer, there was a significant signal of anaerobic respiration caused by the roots having a higher demand for oxygen and outcompeting the microbes. The microbes then have to switch over to using anaerobic respiration.”

One benchmark for interpreting soil processes affected by soil carbon dioxide and oxygen is to calculate the apparent respiratory quotient (ARQ), which combines carbon dioxide and oxygen concentrations into one value. Hodges added:

“If ARQ equals one, that means that aerobic respiration is the controlling process. If there is a significant deviation from one, then that tells us something else is controlling the soil gas concentrations.”

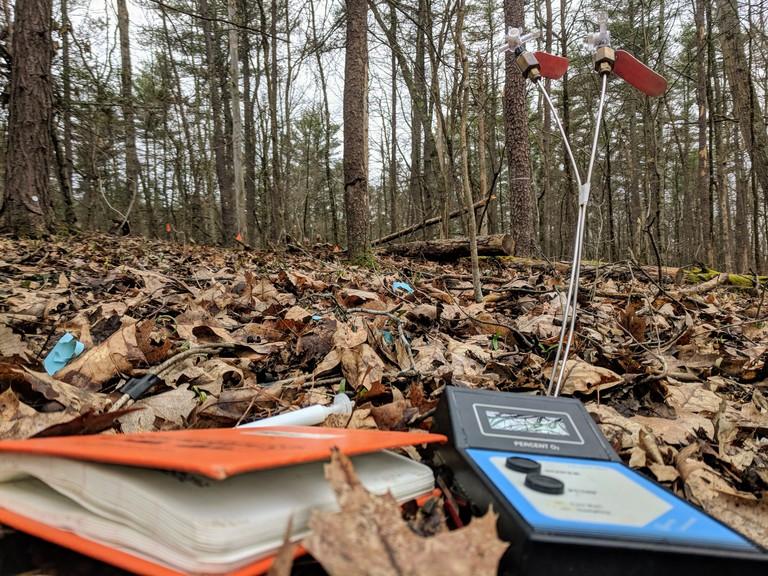

The scientists studied soil respiration in a shale watershed and a sandstone watershed in the National Science Foundation-funded Susquehanna Shale Hills Critical Zone Observatory.

They measured soil carbon dioxide and oxygen levels about 8 and 16 inches below ground and just above the bedrock layer where the soil ends. Susan Brantley, distinguished professor of geosciences and director of the Earth and Environmental Systems Institute (EESI) at Penn State, said:

“Caitlin interpreted gas sampled from soil somewhat like a policeman interprets the breathalyzer test of a tipsy driver. The chemistry of the gas stuck in the soil yields a picture of what the bacteria are doing.”

The team found that ARQ sometimes signaled significant anaerobic respiration by the microbes. During anaerobic respiration, the microbes shifted from using oxygen to oxidized metals, like iron and manganese, for growth. Jason Kaye, professor of soil biogeochemistry, said:

“When we see large numbers in the ARQ, it means we have more carbon dioxide than the oxygen levels would suggest.

“How can that happen? It can happen because CO2 is being produced without oxygen consumption, and that’s exactly what an anaerobic process is. That’s what these large numbers mean. You’re seeing more carbon dioxide than you would expect from aerobic respiration.”

Carbon Dioxide is released during anaerobic respiration

The Penn State team’s research, reported in the Soil Science Society of America Journal, is the first to use ARQ to find evidence of a seasonal pattern of anaerobic respiration in temperate forests. The researchers also calculated the total amount of carbon dioxide — 36 grams per square meter — that leaves the soil system every year due to anaerobic respiration.

They said the conservative estimate constitutes 10 percent of all respiration done by soil microbes at their research sites, which is a large number since scientists don’t think of these humid temperate forests as posting much anaerobic respiration. Hodges said:

“It’s expected that the northeastern United States will have increased rainfall with climate change. We expect that this anaerobic respiration will become a more dominant process in these forest systems, and our soil carbon models don’t yet take this into account.”

Brantley said novel approaches like soil gas sampling are needed to understand how soils will respond to changing climate.

Provided by: Francisco Tutella, Pennsylvania State University [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]