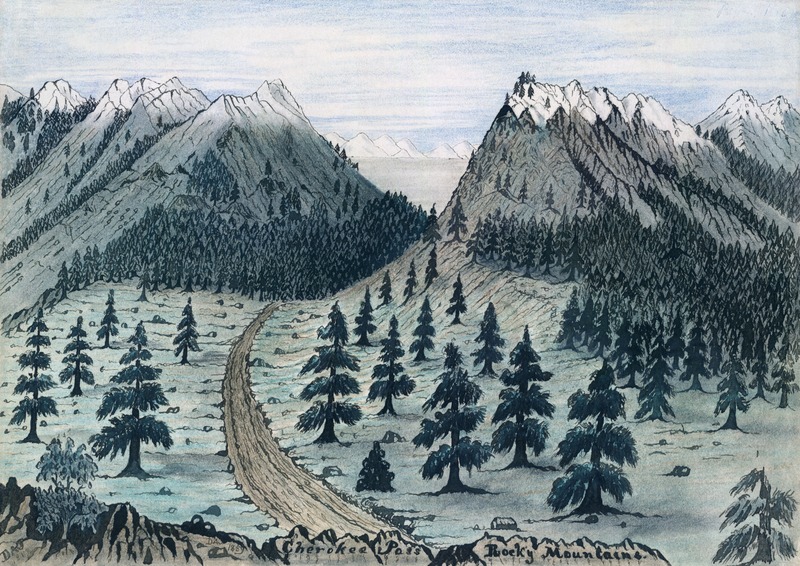

Lamar Marshall, land surveyor, electrical engineer, and anti-logging campaigner, is a world-renowned expert on historic Cherokee footpaths. Marshall has mapped approximately 1000 miles of Cherokee trails in Appalachia.

When the Cherokee Nation governed the southern Appalachians 300 years ago, a network of foot pathways linked over fifty villages and settlements, and many of these paths became Cherokee turnpike routes. Marshall’s largely solo endeavor took over a decade to complete and involved scouring archives around the country for references to secret Indian trails to add to his vast database of historical annotations and Cherokee place names.

Following the CherokeeTrails

In his customary camouflage jacket and pants, a waist-pack loaded with surveying equipment, waterproof boots, a pistol, and map in hand the then-68-year-old surveyed landscapes and old Indian routes. He frequently encountered extreme conditions such as wasp swarms, ticks, chest-high nettles, rainstorms, and hypothermia, which explains why early Europeans avoided many steep trails.

The Cherokees generally traveled on foot in soft-soled moccasins, and although horses were introduced to the tribe in the 18th century, they were seldom used. Legend has it that certain Indian tribes also had a common ritual of marching one after the other such that each man trod in the footsteps of the one before him, with the last in line erasing the imprints, so many Indian roads may have vanished.

Marshall speaks of a time when he explored the Alabama woods clothed in a loincloth and moccasins.“It was just kind of a fun thing to project myself back into time. I always admired the native lifestyle. I love the trails. I love walking on the trails, camping next to the trails. And feeling like right now: what did the first white people see when they came up here?”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

An ardent environmentalist, a formidable activist, and Republican, Marshall says. “Wilderness to me is the ultimate expression of freedom.”

His initiatives have mainly assisted present Cherokees. Marshall created interactive maps using historical timelines and pictures with an archeologist’s help. “This is about trails, but also about the ecology and geology of trails.”

WCU Cherokee language researcher Tom Belt describes the project’s impact on the tribe as “exceptional.” Landscapes are as crucial to the Cherokees’ historical identity, as they are to other indigenous peoples.

“It may be a town or a gas station to the United States or the state of North Carolina,” Belt says, “but at one time underneath it might have existed a very extensive culturally-based community that doesn’t exist now. That’s the kind of stuff we wanna know. What was the name of that place? If you can, even on paper, reverse that process so that you make it clear that there was a Cherokee landscape here, it gives Cherokee people conceptual ownership that in many cases they are currently lacking. We didn’t come into a blank howling wilderness,” he added. “We took over this place,” he said.

Congress approved the Indian Removal Act on May 28, 1830. It authorized the relocation of Native Americans residing east of the Mississippi to the land west of the Mississippi. However, the Cherokee Nation – a grouping of linked communities from Kentucky to Alabama – refused to leave. The Americans and Cherokees had been at odds for nearly a century, and the federal government became powerful enough to simply remove them.

During the deportation in 1838-39, about 4,000 Cherokees died. The road they took west is now known as the Trail of Tears. Many died on route. In Oklahoma and western North Carolina, there are three quasi-autonomous Cherokee districts. They were wiped away but not obliterated. What’s left are mere traces of smudged-out, penciled-over people: cemeteries, clay mounds, dwellings, and tree engravings.

Thousands of kilometers of walkways traversed over the ages connect all of these ancient sites. Cherokee land shrank with each treaty; the younger the map, the less Cherokee area is indicated as theirs. When Marshall relocated to Cowee, Georgia, from Alabama, he kept these old maps in his home office.

Old Maps

The maps improve as they become more defined. The US army developed most of these maps. In addition to taking notes, GPS highlights landmarks. Marshall compares findings to those on the maps, which he carries with him on every expedition. The data gets fed into a computer with GIS software to create digital representations. After one is finished, it’s on to the next one.

During his boyhood in Birmingham, he developed an interest in the Cherokees. (“I hated the concrete, the development.”) Survivalist literature was the first to introduce him to them.“They didn’t have to go to school. They didn’t have to get a job in corporate America. They lived off the land. They were totally free.”

“I have gathered good hops in the woods opposite Nuquose, where our troops were repelled by the Cheera-kee, in the year 1760. There is not a more healthful region under the sun, than this country; for the air is commonly open and clear, and plenty of wholesome and pleasant water . . . almost as transparent as glass.”

James Adair, History of the American Indians

Employed as an electrical engineer and land surveyor, Marshall built a 3,000-square-foot farmhouse in Blountsville, Alabama with his wife and children. They farmed, fished, and lived off the land. However, after the death of their only son, they relocated to a home in Alabama’s Bankhead National Forest.

Marshall got a close-up glimpse of Alabama’s poorly regulated logging sector, which “nauseated” the longtime nature enthusiast. He investigated further and found the Alabama Forest Service’s management plan was “designed in cooperation with the wood industry.” He was furious when loggers destroyed a Cherokee sacred spot known as Indian Tomb Hollow. Marshall and others protested against the Forest Service.

Marshall first founded the conservation group Wild Alabama, which supports conservation and sharing information of plants, wildlife, land, and water in the state of Alabama. Later he founded WildSouth.org, which produced petitions, held rallies, filed lawsuits, gave public speeches, and satirized Forest Service officials in local newspapers for almost a decade. This was his “guerilla warfare” against corporate “tree racists.”

Marshall portrays this period of his life as if he were a combat veteran recalling his service. “I envisioned a band of eco-warriors fighting for the last wild places of Alabama. Native American descendants rose up, and we kicked ass for over a decade.” The “descendants” are the numerous tribal groups who often partnered with Wild Alabama. Marshall himself claims 3% Native American heritage.

There is an earthen mound in a large open field which is an old Cherokee structure. Birdsong resounds over the landscape, and in the distance, there are rounded sloping mountains, powdered white with snow. “This is where the council-house used to be,” Marshall says from atop the mound. He points down to the grass below. “Over here is a depression that they say was formerly a fire pit.”

From up here, it is not hard to envision an earlier Appalachia: savannas with buffalo galore, lush groves of chestnut trees, and the brilliant red-black flash of an ivory-billed woodpecker. The majority of these species are extinct or limited to other states. The broad green plains are gone. Towns are being built upon each other. Words are lost. A new country is on the horizon.

Clutching an old map in his hand, a melancholy expression on his face Marshall sighs and says, ‘The mountains haven’t changed.’