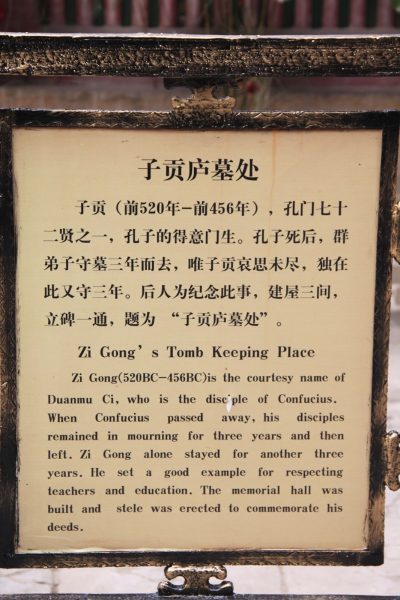

Zi Gong, born in 520 BC, a native of the state of Wei, was one of Confucius’s ten most outstanding disciples. He was well rounded, a well-educated Confucian scholar, an outstanding politician, a diplomat who traveled across the land, and a successful businessman who was rich as a king. As the first Confucian merchant in Chinese history, he and is known as the ancestor of Confucian business practice.

Zi Gong served as minister in the states of both Lu and Wei. When he interacted with the rulers of states, both as a Confucian and a businessman, he rode in a luxurious carriage with four horses and brought generous gifts to the noble Lords. Everywhere he went, he was treated with great respect. The heads of the states followed the rituals of a host and a guest, rather than the rituals of a ruler and a subject.

Zi Gong’s business talent

Zi Gong was one of the best students of Confucius. He was cheerful, animated, well-spoken, witty, perceptive, and well-traveled. He was gifted in business and enjoyed family heritage.

Zi Gong’s hometown was Chaoge, which was the accompanying capital of the Shang Dynasty for four generations and had a robust business atmosphere. Zi Gong was born into a family of merchants and had a great talent for business. He believed that if one had a beautiful jade in the cabinet, one should sell it when the price was right instead of storing it forever. He put forward the theory that “things are precious with scarcity,” believing that the price of a commodity depended on supply and demand.

Conducting business in his travels with Confucius

Zi Gong is said to have started studying under Confucius at the age of seventeen and inherited the family business in his twenties. While he traveled around the world with Confucius, he was also practicing his business skills. He paid attention to each state’s domestic and diplomatic affairs, local customs, and market conditions and profited well by trading based on seasonal conditions and changes in market supply and demand.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

For example, one winter, Zi Gong learned that the state of Wu was planning an expedition to attack the state of Qi. He predicted that the King of Wu would collect cotton and wool for the army against the cold, which would lead to a shortage of cotton and wool for the general public. He quickly arranged to buy cotton and wool from the state of Lu, and then shipped it to the state of Wu. As expected, the people of Wu were dressed in thin clothes and suffering in the cold. When Zi Gong’s cotton and wool arrived, it was immediately snapped up, and Zi Gong made a fortune.

Confucius said of Zi Gong, “he did not wish to serve in the government but rather to engage in business, and he could accurately predict the market situation every time.”

It was recorded in Records of the Grand Historian – Biographies Of Merchants (94 BC) that Zi Gong studied with Confucius, then left to become an official in the state of Wei, and after that he did business between the states of Cao and Lu.

What principles did Confucius teach Zi Gong?

If Zi Gong had not studied under Confucius, he would have still been a fine businessman, given his talent, but he might not have accomplished so much. What truths did he learn from Confucius that made him so outstanding and successful?

Most of the dialogues recorded between Confucius and his disciples in Analects of Confucius were with Zi Gong. He was a ready learner and asked a lot of questions. Starting with one question he then moved deeper, prompting Confucius to give explanations on multiple levels. The brilliant exchanges between the two men are shining with wisdom throughout, benefiting future generations.

Zi Gong once asked Confucius how to govern the country. Confucius replied, “Adequate food, adequate armaments, and winning the trust of the people, that’s all.”

Zi Gong asked, “If one item has to go, which of the three can be dropped?”

Confucius replied, “Remove the armament.”

Zi Gong asked, “If another item has to be removed, which of the remaining two can be dropped?”

Confucius replied, “Remove the food, for people have died anyway since ancient times. But if there is no trust of the people, the state will not stand.”

As the key to good governance of a state, Zi Gong recognized trust to be the essential thing in business too,

Confucius said, “The superior man values righteousness, the lesser man values profit.” He advocated, “A superior man values his wealth and acquires it through proper means.”

Zi Gong had many strengths, but he also had weaknesses. He “liked to praise the strengths of others, but could not bear their faults.” Confucius reminded him three times in the Analects to “forgive.”

Zi Gong considered Confucianism to be a philosophy of life to be kept in one’s heart and used to guide one’s actions. Zi Gong treated people with respect, kept his word, valued his reputation, never harmed others to benefit himself, provided reliable goods and made moderate profits. He made friends everywhere under the motto of “harmony is precious.”

Wealth and morality

Zi Gong became immensely rich and likely recognized the influence of money on people. He asked Confucius another critical question, “What do you think if a man is poor but not sycophantic, or rich but not arrogant?” Meaning, is it enough for a poor man to avoid sycophancy, and a rich man to refrain from arrogance?

Confucius raised his expectations, saying, “It is okay, but it is better to be poor and happy, or rich yet still humble.”

Zi Gong was inspired and followed up with the question, “Is it just like the constant polishing of jade, in that a superior man must also constantly improve his moral state?” Seeing that he had such good enlightenment quality, Confucius was pleased and replied, “In that case, I can talk to you about the Classic of Poetry (compiled by Confucius, 1100-600 BC)!”

Some people hold that Zi Gong was very successful in academics, politics, and business; a model among Confucius’ disciples in applying what he had learned. As “actions speak louder than words,” Zi Gong’s success is a testimony to Confucianism’s practice of “benevolence” being practical guidance to all aspects of life, such as being human, ruling a country, and doing business.

Actually, if one can understand and practice the five constants of Confucianism, “benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and integrity,” and keep improving the moral state just like polishing jade, how could one not be respected, trusted, and successful in business, or any other endeavor? In later generations, business people who have looked up to Zi Gong and embraced his legacy have been celebrated for their integrity.