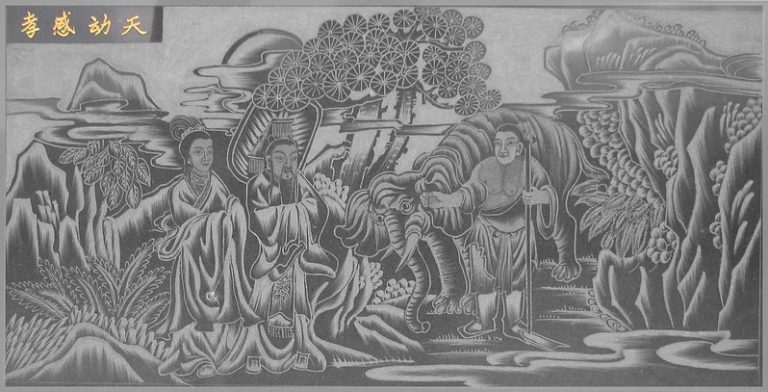

Many tales, myths, and rich traditions have been passed down from ancient China. This well known tale involves filial piety. In ancient Chinese culture, filial piety is considered the fundamental principle of Confucian ethics. It is recognised as the source of all virtue.

These traditional moral principles were largely degraded when the Cultural Revolution reshaped China’s values. The Chinese Communist Party demands allegiance to central authority and condemns traditional values as feudal relics to be eradicated. One is expected to be loyal to the Party, rather than one’s family.

Near the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 – 220 A.D.) a baby boy named Wang Xiang (185–269) was born to Wang Rong and Lady Xue. This was a chaotic period when many warlords were vying for control of the country’s resources.

Lady Xue died when the boy was young, and Wang Rong married Lady Zhu who bore him a son called Wang Lan. Lady Zhu was envious of Wang Xiang. Instead of giving him the sympathy he needed, she resented him and treated him dishonorably. She thrashed him and blamed him for minor matters. His father Wang Rong was swayed by her to participate in abusing him.

Wang Xiang was truly alone.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Yet, over the course of 20 years Wang Xiang stayed with his family, and although he received many an invitation to serve as an official in the local commandery office, he turned them down.

Lady Zhu continued to treat Wang Xiang badly. He was forced to sweep the cow shed every day, and had to shoulder all of the arduous household duties. Wang Xiang always complied with his stepmother’s instructions without raising a voice of dissatisfaction. Everything he accomplished was done with attention and sincerity. His filial devotion for both of his parents was shown despite his terrible treatment.

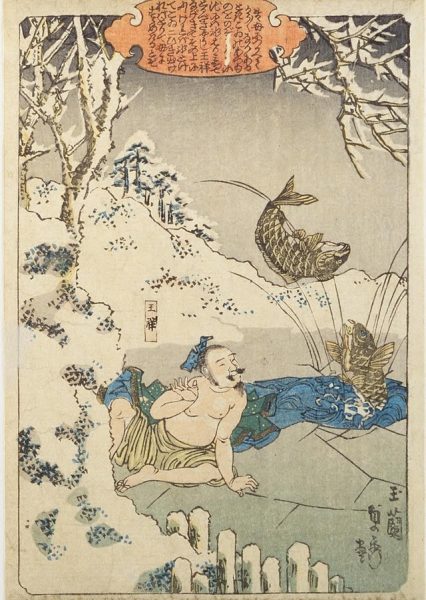

One time, Lady Zhu became so ill that she was bedridden, yet she wanted carp for dinner. Since it was winter, all the rivers were frozen. Wang Xiang thought hard about how he could obtain the desired fish.

He walked down to the river, took off his clothes and lay on the ice so that his body heat would melt the ice. Blue and shivering with cold, Wang Xiang called out to the gods to assist him in fulfilling his wish of filial duty. After a while, the ice underneath him suddenly thawed, and from its frosty depths, out sprang a carp!

Wang’s dedication in the face of unusually cruel abuse became well-known and is encapsulated in the Chinese idiom “Lying on Ice for Carp.”

As Wang Xiang grew, the Han Dynasty was eventually ripped apart by uprisings and civil war. Wang Rong died, and the younger Wang took his stepmother and step-brother, fleeing a long distance from their city. He stayed with them for 30 years.

A local governor was so deeply moved by Wang Xiang’s devotion that he appointed him as a state official. His effective initiatives gained him much respect and admiration from the public. He also became a ceremony minister and advisor to the young Emperor Cao Mao.

Wang died in 269 at the age of 85, having served many decades as a loyal statesman. He was awarded the posthumous title “Duke Yuan.” Wang Xiang is cherished as a perfect model of the highest of all virtues, filial piety. His legacy is widely celebrated and it is still passed down today.