In 1989, Communist China massacred thousands of its own people in the center of Beijing. The effects of that massacre last to this day

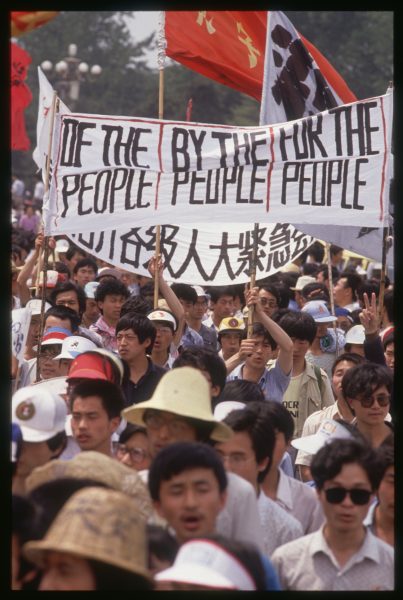

More than three decades ago, there was a brief moment when the Chinese people found the opportunity to govern themselves — and nearly succeeded.

For about three weeks in May 1989, millions of people across Beijing, following the example of students and teachers from schools around the capital, stood out to oppose the widespread corruption of Communist Party officials and to back growing calls for political reform.

From May 13 to the end of the month, as the Party leadership took in the situation and formulated their reaction, residents of Beijing enjoyed an open atmosphere, one that remained orderly and peaceful despite the effective disappearance of state administration.

The protesters converged on Tiananmen Square, which sits before the ancient Forbidden City palace complex and to the east of Zhongnanhai, headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Traffic police left their posts, with many joining in the events, eyewitness Chen Gang, then a college student, remembered. Yet their places were simply filled by volunteers. Locals brought supplies to those demonstrating in the square; despite the size of the crowd, the supplies were distributed fairly and without bickering.

“It was an emotional moment: I had never expected that the communist slogan of ‘Assign the abundant material goods to the people according to their need’ would be first realized there at Tiananmen Square—freed of the Party organization,” Chen recounted in a documentary piece published by The Epoch Times in 2016.

The massive demonstrations would eventually end in the Tiananmen Massacre of June 4, followed up by a merciless wave of repression against those deemed to have played a role in the movement. The “June Fourth incident” remains one of the most heavily censored topics in China, and is seen by many as representing a fateful watershed in the country’s history — when the Party determined to follow the path of Marxist-Leninist authoritarianism, no matter the cost.

However, at the time, there was still much reason for the Chinese — from ordinary citizens to reformers in the leadership — to harbor hope.

The spirit of reform

In the late 1980s, China was a very different place from how it would develop in the decades to come. CCP leader Deng Xiaoping had instituted the “reform and opening up” policy, turning the country away from strict planned economics. As part of this push, Deng allowed liberal-minded officials to rise to the highest ranks of the Communist Party.

Hu Yaobang assumed the post of Party Chairman, then General Secretary. Together with Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang, the two men were praised by Deng as his “left and right hands” in the effort to modernize and liberalize China.

Under Deng — who remained de facto in charge despite not formally assuming leadership — Hu, and Zhao, China saw the dawn of its explosive economic growth. Ordinary Chinese could now start up businesses, a privilege once reserved for state companies. Contacts with the outside world increased as students and entrepreneurs went abroad. A boom in popular culture and intellectual expression materialized.

In a country where communist ideology was written into the constitution and provided the mandate for the CCP’s violent authoritarian rule, economic and social reforms inevitably stirred controversy. However, even the Party leaders were unafraid to push boundaries.

Zhao Ziyang drafted serious plans to separate Chinese government administration from the authority of the CCP, something unthinkable today. Hu Yaobang, for his part, when queried on which aspects of founding communist leader Mao Zedong’s theory were desirable for modern China, he replied that there were none.

And on the ground, the relaxed environment was leading to dissent even before the events of 1989. From the “Democracy Wall” and various attempts to institute local elections in the late 1970s and early 1980s, this dissent grew and led to greater protests for Western-style reforms.

While the Tiananmen Square protests are often remembered for their advocacy of democracy and political modernization, for many ordinary participants, their demands were simpler: reduce the widespread corruption of the Party officialdom, and hold them accountable to the public.

Such demands, whether for greater political representation or practical fairness, alarmed the Communist Party, especially those who already had reservations about straying from the classical Marxist path. In 1987, believing that Hu had gone too far, Deng Xiaoping and other officials forced the general secretary’s resignation, replacing him with Zhao Ziyang. Though Zhao was the architect of Deng’s economic restructuring and an advocate of reform, for millions, the removal of Hu Yaobang was an ominous and unwelcome signal.

A historical tragedy

To many, Hu had personified the hope that China could shift from authoritarianism to democracy. Two years after his forced retirement, Hu’s death on April 15, 1989 sparked an outpouring of national grief.

However, what began as a commemoration for the deceased reformer soon escalated into fresh demands for democratic change. Outside Beijing, protests cropped up in dozens of Chinese cities in a movement encompassing tens of millions.

The 1989 protests occurred in the backdrop of similar popular movements that were in the process of bringing down the Soviet-backed communist regimes in Eastern Europe. But unlike in places like Poland and East Germany, where millions marched to bring down communism outright, many of the Chinese protesters were convinced of the CCP’s ability to change for the better.

Given Zhao Ziyang’s position, he could have, and did, take steps to help the democracy movement. Unfortunately, he was absent for critical executive meetings that shaped the Party’s reaction; in one episode, he was on a state visit to North Korea. Further, hardliners in the CCP saw in the unrest an opening, with Beijing mayor Chen Xitong and Premier Li Peng conspiring to paint the protests in the most alarming manner before Deng.

Already on April 26, after siding with these hardliner opinions, Deng Xiaoping had publicly labelled the protests a “riot.”

The charge clashed with the experience of the college student Chen Gang, that the atmosphere among the protesters was peaceful to the point that “even thieves renounced stealing.”

In particular, a desire to prove that the democracy movement was not violent or anti-CCP was partially responsible for the scenes of order that Chen Gang saw at the time:

“The capital was simply out of the Communist Party’s domain,” he recalled. “Not wanting to give the authorities any excuse to suppress the demonstrations, the students cooperated to institute a meticulous regime of social law and order, starting with directing traffic.”

On and following May 20, when Deng Xiaoping declared martial law and sent troops to clear the protesters, the masses put up nonviolent resistance to the People’s Liberation Army columns entering the city.

The standstill persisted and worsened over the next two weeks. Finally, hardened formations were sent in, wiping out the thousands of protesters who remained at Tiananmen Square in the night between June 3 and June 4.

In the final days before the imposition of martial Zhao Ziyang, his power waning, made a visit to the students at the square: “We came too late. We are sorry. You talk about us, criticize us. It is all necessary.”

In the wake of the massacre, Zhao was removed from his post and placed under house arrest. His successor, Jiang Zemin, had been CCP secretary of Shanghai. He had been chosen for the position because of his proactive stance in shutting down a liberal publication in Shanghai when it refused to self-censor its pro-demonstration coverage.

‘Killing 200,000 in exchange for 20 years of stability’

In the West, the photo of the lone “Tank Man” standing down a column of advancing PLA tanks on the streets is a well-recognized symbol of resistance. But for most Chinese today, living 30 years after the bloodshed that occured in the center of their nation’s capital, the legacy of Tiananmen is a phantom episode of history, torn between activist voices, regime propaganda, and fading memories.

Until recently, with the banning of activities to mourn the victims of Tiananmen in Hong Kong, people in the former British colony would dutifully organize memorial gatherings every year. In mainland China, the events of June 4, 1989 are subject to an Orwellian exercise of reality control and historical revisionism on the mainland.

Apart from censoring all available information regarding the protests, CCP-paid internet trolls, known as wumao, further muddle the waters by offering false or misleading accounts of the protests. And what cannot be denied is simply brushed off as irrelevant in the great flow of China’s supposed rise.

In the years after the Tiananmen Massacre, Deng Xiaoping resumed his reforms, though the political content was now a third rail: in an infamous speech, Deng claimed that it was worth it to “kill 200,000 people in exchange for 20 years of stability.” To be sure, this was an exaggerated figure, based on the Chinese convention of counting large numbers by the tens of thousands. But the point was clear: making money was okay, as long as it didn’t interfere with the rule of the Communist Party.

Deng’s logic has been acted out at a dramatic scale and with mind-boggling intensity. Starting in the 1990s, under the leadership of CCP leader Jiang Zemin, Party officials were officially permitted to get involved with business, marrying the authoritarianism of the Communist Party to full-on commercialism. Jiang called upon cadres to “keep quiet and make huge fortunes,” something they did at any cost.

Under the blanket of China’s economic rise — from having a GDP comparable in size to that of Tokyo in the 1990s to being the second in place behind the United States — the CCP only reinforced its totalitarian means. Jiang Zemin’s persecution of the popular Falun Gong spiritual practice opened up the door to repressions of other politically undesirable groups, and the influx of money gave Beijing access to a wide range of upgrades for its modern authoritarian state. The list goes from Western-sourced computer chips used in the Huawei-built mass surveillance systems, to immunosuppressant drugs for transplants of organs harvested from prisoners of conscience.

The consequences of Tiananmen and the bloody end of political reform are apparent. Like advanced western democracies, China has become an increasingly materialistic society, with endlessly rising levels of consumption and veneration of socioeconomic status. The Communist Party no longer claims to represent the people on account of Marxist merit, but in accordance with how rich it can make them.