Jeff Harper, a former Iowa Wesleyan College basketball player, was detained in a special form of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) prison for eight months before being released in September of 2020 without ever being formally charged with a crime. The American’s nightmarish ordeal highlights the appalling conditions of the Party’s so-called “residential surveillance in a designated location” system.

“They completely separate their justice system from ours,” said Harper in a June 22 Wall Street Journal article. “I’m not a fan of it.”

The 33-year-old baller was in Shenzhen for a five-day tournament in early 2020. While in the city, the 6-foot-9 Harper, a black man from Tennessee, allegedly intervened in a violent fight between a couple. In the woman’s defence, Harper shoved the man, who later fled. Harper was arrested by the Communist Party’s public security apparatus and taken to an undisclosed location.

Several months into his detention, Harper was told the man he had pushed fell into a coma and later died. However, he was neither charged with a crime nor appeared in court during his eight months in prison.

Harper said his detention facility was not a normal prison, however. Instead, he was left in a room resembling an apartment, which had only a rancid mattress and a plastic chair. The man said that although he wasn’t physically abused, he was mentally and emotionally tormented by the uncertainty of not knowing what the authorities were going to do to him.

‘Separation is one of the hardest things for the human mind’

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

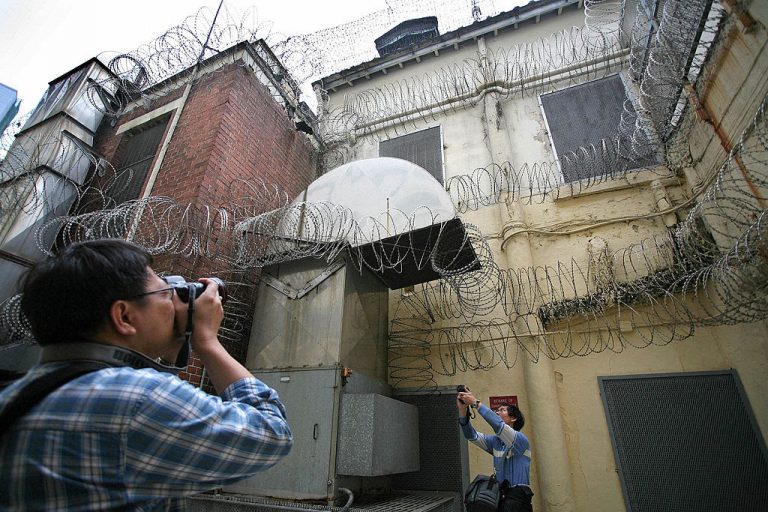

“Residential surveillance” is simply a palatable word for being detailed under something similar to house arrest, except one is not confined to one’s own home but in a facility designated by the communist regime. The facilities are often referred to by detainees as dark dens or black jails. Once held within, one is isolated from the outside world, friends, family, and even defense lawyers.

According to WSJ, investigations by various human rights groups led by Safeguard Defenders, a Madrid-based nonprofit team focusing on human rights in China, revealed that in 2020 alone, 5,810 cases utilizing the residential surveillance tactic were filed in the Chinese court legal databases.

It is unknown how many undocumented detainees in the system there are.

The group, who have been tracking the residential surveillance practice, say the number has doubled in the last year, not counting the ones that are hidden. Peter Dahlin, Director of Safeguard Defenders, is personally a survivor of CCP detention after he ran a legal aid non-profit before being deported in 2016, said residential surveillance “Is used extensively.”

Dahlin was criticised and accused by Party media of endangering state security by providing financial support to human rights lawyers. Safeguard Defenders was established by Dahlin after he left China.

Human rights bodies at the United Nations were presented with findings from Dahlin’s organization and criticized the practice. Most of the people suffering under residential surveillance are none other than Chinese citizens.

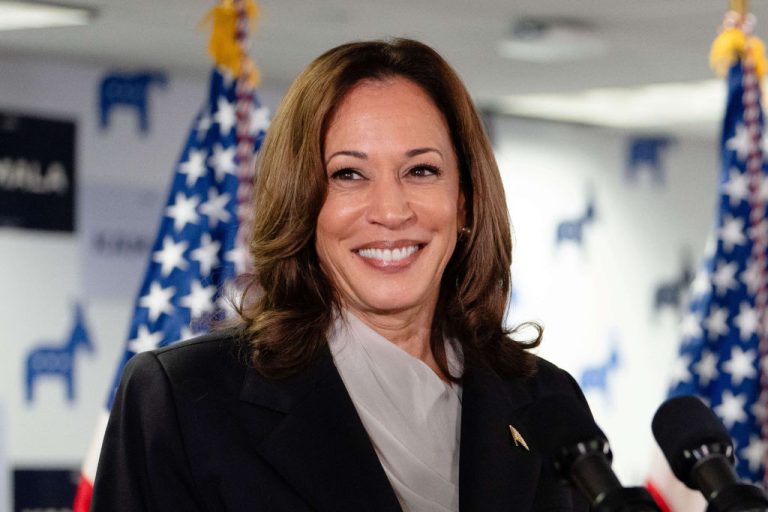

The CCP’s exploitation of its citizens recently received international attention when G7 leaders, along with President Biden, made public statements about some of China’s human rights abuses at this year’s Summit, pledging to be proactive in counteracting matters such as the Uyghur genocide and annihilation of Hong Kong’s democracy.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Zhao Lijian, hit back at the U.S. in a typically Communist Party hawkish rhetorical style during a briefing on Tuesday, “The U.S. is sick, and it’s very sick,” said Zhao. “The G-7 should check America’s pulse and prescribe drugs for it.”

Although some subjects detained under residential surveillance are freed and all charges dropped, as in the case of Harper, the process may often take years before being resolved. The overwhelming majority of cases that do go to trial in China’s faux legal system are determined as a conviction before they even begin.

For Uyghurs and other minorities who are held in labor camps, which the CCP claims are so-called “vocational schools,” they are monitored day and night under constant technocratic surveillance, and their exact whereabouts are not known to the outside world. Often, only a note from the authorities to the next of kin is left, unceremoniously stating that the person in question is now part of an investigation at an undisclosed location.

Harsh isolation

Harper said what kept his hope alive was prayer, exercise, and a dream that one day he would get out of his jail and board one of the planes he had heard or seen flying in the sky above. He told WSJ that he didn’t even know where he was or that there was a pandemic. Fortunately, his girlfriend tracked his phone and he was eventually allowed to meet with a lawyer and U.S. consular officers.

“Isolation is one of the hardest things for the human mind,” he said.

Although China’s 2016 “Human Rights Action Plan,” claims to curb residential surveillance and improve conditions and shorten duration, there are still many of China’s people, ordinary and famous alike, who have been subject to the practice.

For example, literary professor Liu Xiaobo, 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, died in custody in 2017 at the age of 61. Ai Weiwei was also subjected to residential surveillance for 81 days. After release, Ai created artwork depicting the treatment he suffered at the hands of the CCP, which helped expose the practice to the public.

Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor were also subjected to residential surveillance for a small period of time when they were detained in December of 2018 by CCP authorities in a retaliation move after Canada arrested Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver on an extradition warrant from the Trump administration.

The Two Michaels have been detained ceaselessly ever since without access to consular services, and are now awaiting trial.

There are also many ordinary detainees including lawyers and journalists who are isolated to be convicted. Some prisoners have vanished for years such as members of the spiritual group Falun Gong, Christians, and Hong Kong dissidents.

Safeguard Defenders also presented examples of the kind of places where prisoners were held and the conditions under which they were being kept. They said suspects are often tortured, abused, and interrogated with “tiger chairs,” a method where the person’s arms and legs are tied to a small stool and then kicked.

Harper said he lost 40 pounds in custody after a daily meal of just rice that was at times infested with worms.

Safeguard Defenders were also given documents from former detainees in which the English-language pamphlet laid out rules for those under residential surveillance.

“Sleep on your back and always place both hands on top of the blanket,” it instructs.

Another document requires a pledge which specifies that no details about living conditions are allowed to be revealed, especially to overseas media, as a term of release.