Woodblock printing has made significant contributions to the dissemination of information, insight, and creative inspiration. It is the simplest, and slowest of all textile printing methods; yet, it is able to produce fine artistic results, some of which are otherwise impossible. A renewed interest in woodblock printing may help revive this ancient art form.

More than two thousand years before Europeans invented the printing press, the Chinese perfected a method of printing that relied on hand-carved wooden blocks. These very early blocks were used to set ink on silk and later on paper. The oldest woodblock printed pieces that have survived are of silk that has been printed with flowers in three colors and dates back to the Eastern Han (25–220 CE) era.

The use of circular “cylinders” to attach objects to clay tablets goes back to the earliest civilization of Mesopotamia before 3000 BCE when they were a masterpiece of surviving art, and they included intricate and beautiful images. The earliest recorded papermaking technique in China was discovered during the Han era, by the court official Cai Lun. Early paper was made from hemp, bark fibers, linen, and even fishing nets.

A completely functional writing system had been established in late Shang-dynasty China as early as 1300 BC.

In both China and Egypt, the use of small stamps began before the use of large blocks. In Egypt, Europe, and India, textile printing certainly preceded the printing of paper or papyrus. Advances in carved seal-making and the discovery of paper enabled block printing techniques to flourish. In the 7th century, Buddhist monks required numerous copies of their sacred sutras. The demand for information outpaced their ability to manually copy. Thus, the four elements of written communication were born: Text (writing), a substance (clay and various forerunners of paper,) a medium (ink) for making text or symbols visible, and a technique (the seal) for transferring ink to the tablet.

Block Printing

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The answer to printing en masse was block printing. A monk would write the words in ink on paper. He would carefully transfer the written side to a woodblock covered in rice paste, so that the inked letters clung to the block, but the paper didn’t. The ink-free areas were meticulously carved away, with a knife or chisel, leaving the inverted text in relief. Woodblock printing is strenuous. To carve the wood, the artist must be still. If he makes a mistake, he must redo the block.

When the block was finished, the printer would cover it with paper. By rubbing the paper with a brush, the text was imprinted on the paper. Because the effort left a heavy impression on the paper, only one side was printed. Aside from the tedious carving of the woodblock, this new mode of text transmission was a major breakthrough. In weeks rather than months or years, a single book could reach hundreds or thousands of monks. By 1000 they had printed all their writings in 12 years, using 130,000 woodblocks.

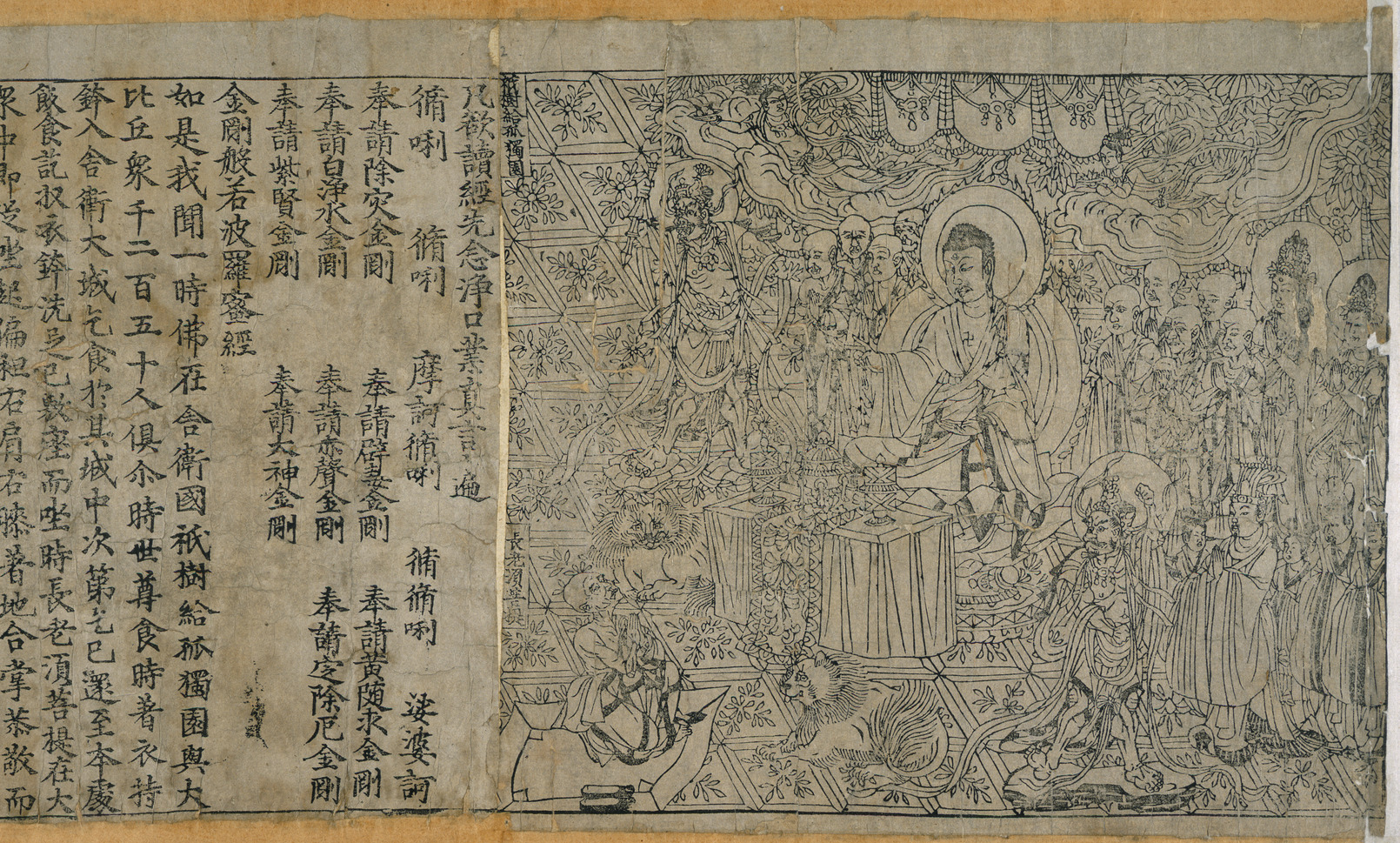

The prints expanded quickly across the Buddhist world as a result of the “new” technology. It was during the Zhenguan years (627-649 AD) that a Chinese writer called Fenzhi first stated in his book Yuan Xian San Ji, written during the Tang Dynasty, that the woodblock was used to print Buddhist texts. The Diamond Sutra scroll measures about sixteen feet long and is the world’s oldest (868 AD) printed book. It was discovered in 1907 by Sir Marc Aurel Stein in Dunhuang’s Mogao Caves and is currently in the British Museum. The book’s design and layout are mature, indicating a strong woodblock printing heritage. It was produced by printing reversed panels of hand-carved woodblocks.

The standardized edition of the Twelve Classics was produced from 932-955, along with other histories, philosophical writings, encyclopedias, and medical literature. In 971, Chengdu finished the Tripitaka Buddhist Canon (Kaibao zangshu, 開寶藏書)). The text took 10 years and 130,000 blocks to print. The Sichuan edition of the Kaibao Canon, known as Kaibao Tripitaka, was printed in 983.

In 1045, a blacksmith and alchemist named Bi Sheng ((毕昇 ) developed a movable type of press. Because of Pi Sheng, printers no longer had to carve out a new block of wood every time they wanted to print something; they could utilize prefabricated pieces of type and arrange them as needed. Pi Sheng used baked clay type on an iron frame covered with hot wax. After cooling the wax, he utilized the tray of letters to print pages onto the surface using his movable press.

Afterward, Tsai-Tung (fl. 1390) ordered Korean engravers to make a printing press from bronze, which was even more durable than clay.

However, Because the Chinese language has a character set that numbers in the thousands, rather than a 26 or so letter alphabet, woodblock printing is preferable to moveable type printing because characters only need to be produced when they appear in the text rather than at regular intervals.

During the Ming era (1368-1644), printed artworks could attain full color. Color printing involves the use of several blocks, each of which represents a single color, with overprinting resulting in the appearance of additional (blended) colors on the print. By keying the paper to a frame, it is possible to print in several colors. The variety of prints available on the market had increased the popularity of woodblock printing. With Lunar New Year prints and other paper offerings, the woodblock prints told stories about people and places, spreading knowledge and insights.

The Printed Products

There were also printed artworks to enjoy and appreciate like printed chess boards, Chinese opera prints, and lantern prints. Among the most renowned were the popular chess board game called “Rising to High Places,” as well as The Journey to the West and Tales of the Three Kingdoms. Traditional stories, mythological and historical figures, flowers, and birds are among the most common themes for lantern prints.

Chinese New Year prints are usually utilized as decorations. People clean their houses and decorate for the New Year. Flowers and fish are among the recurring motifs in the designs. The aim is to conjure peace and harmony for the New Year.

Western Europe lagged much behind the East during this period of growth and did not even have paper until the 14th century.

In a tremendous historical irony, the West soon surpassed the East. The advent of paper in the fourteenth century triggered a minor information revolution. The movable-type press would transform society for generations to come. This innovation hastened the spread of reading, sparking the Reformation and other movements that altered Europe’s cultural fabric.

In contrast, East Asian printers relied on and improved on the block printing method developed by Chinese Buddhist monks in the seventh century.

Introduction of Lithography to China

In the late-19th-century Western lithography was brought to China. The mechanical technique enabled mass manufacturing, and the printing results were stunning. Publishing books, journals, newspapers, and promotional materials became popular using lithography.

Sadly, the Cultural Revolution destroyed many of the country’s traditional workshops, causing a decline in woodblock production.

Many ornamental items such as textiles and wallpaper have been block printed. This is simplest with repeating patterns consisting of one or a few tiny to medium-sized motifs (due to the difficulty of carving and handling larger blocks). For a multicolor design, each color element is carved, inked, and applied separately. Only a few traditionalist companies still employ block printing to produce wallpaper. It is still used to make fabric, especially in artisanal settings.

Chinese woodblock printing is a tradition that is now in the process of dying out. There aren’t many individuals who practice the skill of woodblock printing these days since it is not a lucrative career and society is more concerned with accumulating wealth and improving one’s social standing. The art of ukiyo-e woodblock prints is very rare, with only a few masters remaining in the world. Once this tradition is lost, it will be very difficult to revive this art.