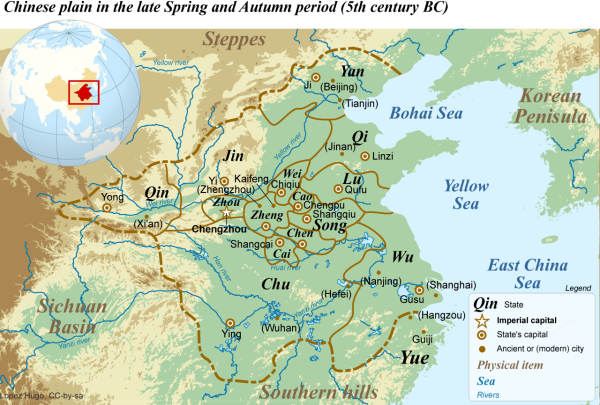

The Spring and Autumn era (770–475 B.C.) was one of the great episodes that shaped Chinese history and culture. It was the time when thinkers like Confucius and Lao Zi articulated and spread their teachings, but also an era of disunity, when the leaders of China’s feudal states vied for influence over the weak royal court.

During this era, the patchwork of large and small vassals that made up the Eastern Zhou Dynasty saw the rise and fall of several political powers, known to history as the Five Hegemons (五霸).

There are different opinions about which rulers deserve a place on the list of Hegemons. But all agree that the first among them was Duke Huan of Qi State, and that the man who made his achievements possible was the storied lawmaker, strategist, and philosopher: Prime Minister Guan Zhong (管仲).

A friendship for the ages

Guan Zhong’s talents — and thus the rise of Qi — may never have had a chance were it not for his lifelong friendship with Bao Shuya (鮑叔牙), who was the son of a wealthy family but did not look down on Guan Zhong for coming from an impoverished background.

When describing his bond with Bao, Guan famously commented: “My parents gave birth to me, but it is Bao who knows me best.”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The extent of Bao’s support and loyalty to his friend is described in the Shiji, one of China’s oldest and most detailed historical records.

When they did business together, Guan Zhong would take more than his share of the profits. But Bao Shuya did not think him greedy, for he knew that Guan was poor and needed the money more than he did. Sometimes Guan Zhong would come up with business plans that lost money. Bao did not think he was dim-witted, but accepted that a man will have successes and failures no matter how intelligent or hard-working he is.

Bao Shuya also served with Guan as comrades in war. Guan Zhong fled from battle three times, but Bao did not see him as a coward, as he understood that Guan had an ailing mother he had to care for.

Their friendship was so unshakable that it later became a set phrase in Chinese,”the friendship of Guan and Bao” (管鮑之交).

Wherever Guan Zhong went, Bao was there to support him, as he believed in his abilities and potential. To Bao Shuya, Guan would owe his career and his life.

Starting a political career in chains

Qi State was located on China’s eastern coast, in what is today’s Shandong Province. Its ancestral founder was the legendary minister Jiang Ziya, but by Guan Zhong’s time, the leadership had fallen into disarray.

During a succession crisis, two of Qi’s ducal heirs struggled with each other for control. When the stronger of the two prevailed, the loser escaped to Lu, a neighboring state.

As fate would have it, not only had Guan Zhong been employed by the unsuccessful challenger, but during the political struggle, he had even tried to assassinate his boss’s rival, who was now on the throne as Duke Huan of Qi.

Just about the first thing Duke Huan did after securing power was to demand that Lu State put the escaped rival heir to death. Fearing invasion, Lu’s government complied.

Then there was the matter of the man who had tried to assassinate Duke Huan. Guan Zhong was extradited back to Qi as a dangerous criminal. He was kept in chains and delivered across the border in a cage.

Guan Zhong thought he was done for. But instead of being sent to prison or executed, he was brought before the duke himself, who received Guan Zhong with the respect due a teacher or an elder.

It turned out that Bao Shuya was in the service of Duke Huan all along. At first, the duke was furious and demanded Guan Zhong’s head. But Bao, as ever, pleaded Guan Zhong’s case and the duke listened. More importantly, Bao Shuya was so confident in his friend’s ability that he told the ambitious duke the following words:

“If you want to govern just one state, then I, Bao Shuya, am capable enough. But if you wish to rule the world, then you must employ Guan Zhong.”

Duke Huan was willing to give it a shot. After coming to power in the year 685 B.C. he promoted Guan Zhong to the equivalent of prime minister.

A rich nation and strong army

The duke and his new minister got to work immediately. Duke Huan was eager to stabilize his country after years of political turmoil. To do this, however, he would need the support of the people.

Guan Zhong recommended starting with enriching the nation.

“When the people are rich, they will be easy to govern. It is often the case that a peaceful country is wealthy while a chaotic country is impoverished. This is a self-evident truth,” he observed.

“But with the people fat and happy, how will we recruit soldiers for our armies?” the duke asked.

“We should value our troops’ quality over their numbers,” Guan Zhong said. “With high morale and good training, we need not worry about them lacking ability in combat.”

Guan Zhong believed that through keeping the country rich and the military strong, it would be possible to gain great power.

The duke was excited by the prospect of dominating all China, but Guan warned him against rash action.

“Our biggest priority now is to improve the lives of our people and enrich the nation. If we can’t even do that it’s useless to think about dominion over anything.”

‘Managing the mountains and seas’ through moral law

Guan Zhong was determined to run Qi State like a giant business venture. But at the same time, he understood the core importance of morality in building a peaceful and stable society.

Many generations before Confucius was born, Guan Zhong advocated similar social principles of upright behavior, which are known to the Chinese as li yi lian chi (禮義廉恥), or “rituals, justice, modesty, and honor.”

These moral codes underpinned the system of laws that Guan Zhong used to set the country in order. At the time, most countries had a simple and oftentimes arbitrary form of government, with kings, nobles, and officials merely giving orders to their subjects. “Legality” was a novel concept.

While Guan and the duke encouraged the growth of business and trade to bring in wealth, they also boosted government administration in their effort to “manage the mountains and seas” (管山海), implementing regulations that not only accounted for profit, but which also fit with the geographical conditions, natural resources, and national security of Qi State.

The capital was divided into districts, which were mainly of two types: mercantile districts, responsible for producing the state’s commercial revenues, and attendant districts intended to provide manpower for the state army. Administrators were appointed at all levels across the nation to ensure effective communication between the people and the central government.

Strengthening the state without burdening the people

Aiming to improve government revenues without affecting the nation’s families by increasing taxes, Guan carried out the monopolization of natural resources to manage market prices. Under his policy, the companies that extracted iron from the mountains and salt from the seawater would sell their outputs to the government, which would resell the refined products to the households at a slightly higher price.

Guan also changed the tax laws, charging these fees based on individual families rather than the association of houses. In addition, land throughout the nation was to be taxed according to its productivity, thus abandoning the century-old well-field system, which relied mostly on privately managed fields.

His ideas were particularly effective in revitalizing Qi’s economy. Guan ordered that wagons arriving empty at state-run markets, as well as individuals carrying goods on foot, were not subject to tolls, thus encouraging trade. Under his leadership, food prices were also regulated, allowing certain products to be available on the market even during lean years.

In addition, Guan created four social categories based on people’s talents: scholar-officials, peasants, workers, and merchants, which became the four traditional occupations of ancient China (士農工商). These classes, which were not hierarchical nor hereditary, laid the foundations for an effective method of selecting talented people for government positions. In this way, Qi administration shifted from the traditional hereditary aristocracy to a professional bureaucracy as the new method of appointing officials.

Qi State also became one of the first countries in the world to organize and keep track of its citizens for administrative purposes. Villages and communities were tallied and registered so that in times of war or crisis, people could be easily mobilized. The moral values and national culture that Guan Zhong emphasized also helped foster a sense of unity among the entire people.

‘Honor the king, expel the barbarians’

In the same way that Bao is remembered for his loyalty to friends, Guan was praised for his loyalty to the country, and gave his all to raise its status among the feudal states of China, creating the famous Hegemony of Qi.

Hundreds of years before Guan Zhong was born, China was united under the Zhou royal dynasty. But the Zhou kings became weak and ruled as mere figureheads. The dukes of the feudal states governed like kings of their own. Meanwhile, foreign tribes often invaded China and sometimes even threatened the continuation of its civilization.

Guan Zhong’s great achievement was to restore the honor of the Zhou king and create common ground among the Chinese states so that they could resist the barbarian invasions, known by the Chinese saying “honor the king, expel the barbarians” (尊王攘夷). To do this, he relied on securing the trust of both the king and other states.

A relatively major example is recorded in the Guanzi (管子), a work detailing the philosophy of Guan Zhong that was compiled after his death.

Early on in Duke Huan’s rule, the duke hosted a banquet with an entourage from Qi’s neighbor, Lu. During the feast, a Lu official drew a dagger and held it to Duke Huan’s throat, demanding that a piece of land that had been seized by Qi be returned to Lu. Faced with the choice of his life or Qi’s honor, the duke promised to give back the land, and the Lu official let him go.

Furious and humiliated, Duke Huan wanted to renege on his promise. But Guan Zhong stopped him. If Qi went back on its word, it would destroy its credibility with other states.

Guan Zhong also insisted that, as a matter of proper ritual, Duke Huan show respect to the Zhou king at all times, even though the king had little real power. As a result, Qi State’s respect for the royal court earned it fame around China and other feudal states were willing to cooperate with Qi. All in all, Qi State managed to arrange nine alliance meetings of the feudal rulers. Though not all their disagreements could be resolved, doing so in the absence of a central government was no small feat.

Even in 651 BC, when Qi’s status in China was unparalleled and Duke Huan was of advanced age, Guan Zhong still required him to kneel before the Zhou monarch. Doing so was a sign of respect for the whole Chinese nation and an example for posterity.

Guan Zhong’s legacy

Guan Zhong is commonly credited with writing the Guanzi, one of the longest philosophical and economic texts in ancient China. Covering a wide variety of subjects such as monetary systems, banking, taxation and trade; this book provides the first-ever description of the quantity theory of money as well as a clear articulation of what would be known centuries later as the law of supply and demand.

What makes this book even more unique is its combination of Confucian and Daoist ideas as a necessity for any political leader. In its chapter on “Inner Enterprise/Training,” meaningful advice is given to the reader:

When you enlarge your mind and let go of it,

When you relax your [qi 氣] vital breath and expand it,

When your body is calm and unmoving:

And you can maintain the One and discard the myriad disturbances.

You will see profit and not be enticed by it,

You will see harm and not be frightened by it.

Relaxed and unwound, yet acutely sensitive,

In solitude you delight in your own person.

This is called “revolving the vital breath”:

Your thoughts and deeds seem heavenly. (24, tr. Roth 1999:92)

Yet for all of his keen laws and moral exhortations, the success of Guan Zhong would have been impossible without his strong personal character and legendary friendship with Bao Shuya.

Furthermore, the tolerance and magnanimity of Duke Huan himself was also instrumental to securing his and Guan Zhong’s places in history.

Unfortunately, things did not continue this way after Guan Zhong and Bao Shuya died. The duke was unable to find a suitable replacement for his loyal and capable prime minister. Traitors stole into government and usurped power in 643 B.C., locking the duke within his own palace walls until he starved to death. Qi State was weakened by the chaos and would never regain the place it had under Duke Huan’s hegemony.

Nevertheless, Guan Zhong stands out as a unique figure in China’s early history. While his moral views could be described as similar to those of the later Confucius, he was sometimes criticized for relying on laws and government control to achieve results. Some scholars also called him a hypocrite for switching sides at the beginning of his career rather than being loyal to — and dying with — his first liege.

However, Confucius himself would later praise Guan Zhong as a man who could swallow humiliation and hardship for the sake of a higher goal, saying that his honor was “not like the honor of a common man or woman who might commit suicide in a ditch without anyone knowing.”

Guan, Confucius said, saved China from collapse by being a hero who put the honor and survival of his country above his own personal reputation.

Meanwhile, Guan knew that he was not a perfect gentleman, and reserved that description for his loyal friend Bao Shuya. If Guan was a model for an effective and upright official, Bao was a paragon of honesty, trust, and uncompromising will. In the years following his death, Bao established himself in Chinese culture as a model of loyalty among friends.