By Natalie Nesbitt, Vision Times UK Staff

Thursday, Dec. 22, is the Chinese winter solstice known as Dongzhi (冬至), which means “Winter’s Arrival.” It is celebrated when the night is the longest and the day is the shortest. The origins of Dongzhi date back 2,000 years ago, during the Han Dynasty, which is made up of the Western Han (202 BC–9 AD) and the Eastern Han (25—220 AD).

A wise man named Zhou Fang calculated the winter solstice using a sundial, essential in the agricultural society of ancient China. The projecting piece on a sundial shows the time by the position of its shadow, which, alongside the lunar calendar, was an important part of everyday life as people relied on a deep understanding of the seasons to survive.

The festival’s tradition is based on the ancient philosophy of yin and yang, which represent universal harmony and balance. In the dark winter solstice, negative yin energy peaks. From this point on, it starts to give way to the positive yang energy, which grows as spring approaches and there are longer light days.

Based on a belief that when days are short, there is limited yang energy, according to Chinese medicinal cuisine, during such times, it is good to eat food with high yang energy, such as warming and spicy foods like jiaozi (餃子), fatty dumplings containing meat and high yang warming herbs, such as ginger and garlic.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

In addition, Quinoa, mustard greens, cherries, strawberries, shrimp, chicken, and lamb are good to balance yang. The basic ideas of Chinese food therapy concerning yin/yang balance, health and well-being can be found in the Huangdi Neijing (The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine).

During the Han, Dongzhi became an imperially recognised traditional festival. The arrival of winter, or Dongzhi, has always been an important day in the ancient Chinese calendar because it was the day that the emperor conducted the most sacred ceremony at the Temple of Heaven in Beijing.

The emperor would refrain from eating meat and drinking alcohol for three days. At sunrise of the morning of Dongzhi, he performed a sacred ritual at the Altar of Heaven, including prayers. Then, wearing his best imperial attire, he climbed the three-tiered white marble platform at the Temple of Heaven and knelt to pray for auspiciousness in the coming year.

Traditionally Chinese people celebrate Dongzhi Festival primarily by worshipping heaven and ancestors. Such worship of heaven on Dongzhi has existed since the Han Dynasty.

Many temples were built, including the famous Temple of Heaven in Beijing, structurally based on heaven being round and earth being square. It was believed that heaven worship would bring a great harvest and good health for the coming year.

To worship, people set up incense burners in front of their ancestors’ tablets and some food such as dumplings, steamed chicken, or cooked pork as a symbolic offering to their family ancestors. In some eastern parts of China, people take food and incense to their ancestors’ tombs, sweep the graves and remember their ancestors during the winter solstice festival.

‘The Nines of Winter’

During wintertime in Northern China, there is 数九 (Shǔ jiǔ), literally “counting nine”, marking nine periods of nine days starting from Winter Solstice (冬至) day (usually 21 or 22 December) 81 days forward when the farmers begin to work on the lands. While Chinese New Year is called Spring Festival, for some, real spring starts only after the ‘Nine Nines of Winter’ have passed.

‘Chart to Pass the Cold’

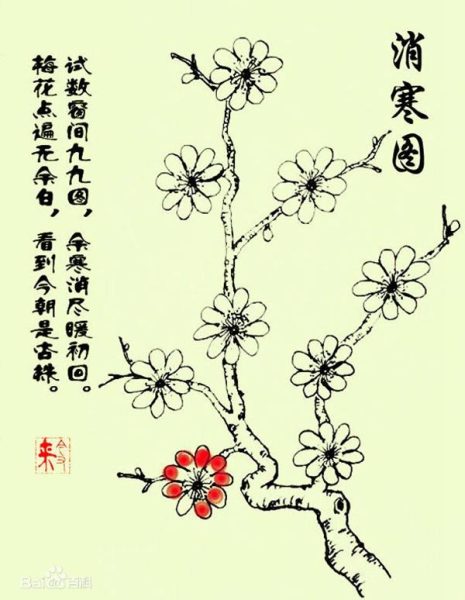

Similar to the Western advent calendar, in which one has to open up a little window each day, leading up to Christmas, the Chinese have a kind of chart known as the 九九消寒圖 , the “Chart to Pass the Cold.”

This chart, which has a time span of 81 days (9×9, a significant number), starts to be crossed off on the day of the winter solstice. Chinese people believe that spring will come after nine periods of nine days starting from the Winter Solstice. When the 81 days have passed, it is well into March, at the beginning of spring.

Nine is considered the largest number in Chinese culture, symbolising the maximum, fullest extent or eternity. The “counting nine” tradition started in the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589 AD).

The elite class had an elegant way of counting down winter. They carefully selected a line of a poem which contained nine characters, with each character composed of nine strokes. They then wrote one stroke each day. By the time the poem was complete, spring had arrived.

This kind of calligraphy or painting is also called a “chart to pass the cold.” Another artistic way to calculate the coming of spring was by painting a plum tree with nine blossoms with nine uncoloured petals. The real spring flowers will bloom when each petal has received a colour. Using the cold-passing chart, the ancients got through winter by counting the days until spring.