In addition to finding a prominent scapegoat for the embattled Chinese real estate sector, the Sept. 28 news of the arrest of Evergrande CEO Xu Jiayin probably had a deeper political dimension, according to long-term observers of factionalism in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Late in September, the embattled Chinese real estate sector saw another shake-up when Evergrande, one of the country’s largest developers, announced that the “relevant authorities” had arrested its CEO Xu Jiayin on “suspicion of illegal acts.”

Per Bloomberg News, Xu, who hails from north-central China but is also known by his Cantonese name Hui Ka Yan, was taken away by Chinese police earlier in September and placed under the dreaded “residential surveillance at a designated location.”

Xu’s downfall was accompanied by the apprehension of many other Evergrande executives in recent weeks, including former top managers associated with the company and its subsidiaries.

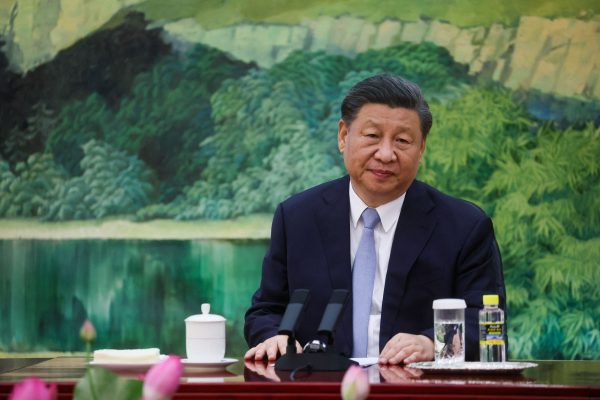

According to observers of factionalism in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the property developer’s arrest and investigation probably had a deeper political dimension, one involving struggles between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and his long-term rivals in the regime establishment.

When the axe falls

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

As described in an Oct. 1 report by the Wall Street Journal, the CCP authorities were proving Xu Jiayin over his effort to transfer assets offshore while Evergrande was struggling to complete unfinished projects, according to individuals familiar with Beijing’s decision-making.

But according to risk consultancy SinoInsider, the economic aspect is insufficient explanation for why the Party decided to move against Xu at the time it did, given that he had already been “constantly moving assets abroad, including before and during the Evergrande crisis.”

Rather than suddenly losing patience with Xu’s transgressions over the years, the SinoInsider analysts believe that Beijing had decided to take down the Evergrande head for political as well as economic decisions, particularly since the Xi Jinping leadership “appears to no longer harbor such illusions” about preventing a “hard landing” for the troubled Chinese real estate market.

In addition to the economic ravages of the three years of “zero-COVID” lockdowns as well as the likely demographic impact they had on China, the country has also entered into a “balance-sheet recession,” further depressing incomes and hence demand for housing.

While the CCP has attempted to resuscitate the real estate market in the post-pandemic era, its latest efforts have fallen flat.

This July, the Politburo announced that it would “adjust and optimize real estate policies in a timely manner,” while local governments took steps to roll back or even completely erase restrictions for purchase in the months that followed.

But Oct. 1 data from the China Index Academy indicated that transaction volumes of new commercial housing in China’s largest and richest cities fell sharply in September, in some cases by between 30 and 60 percent as compared with the same period in 2022, when the “zero-COVID” regime was still in effect.

And during the “Golden Week” holiday period from Oct. 2 to Oct. 8, normally a peak transaction period for China, commercial housing sales failed to pick up, slumping 30 percent year-on-year and were down 70 percent from the previous week, according to China Index Academy.

SinoInsider noted that the desperate measures taken by China’s regional governments to raise sales could have unforeseen negative consequences.

“Some local governments have been removing price floors in late August to early September to drive up sales. But the scrapping of price floors also affects property value,” the analysts wrote in an Oct. 13 piece.

As described by ANZ in a September report, a 30 percent drop in property values could see 12 percent of China’s $5.3 trillion mortgage book become negative equity, while a drop of property prices by half would see negative equity rise to 19.8 trillion yuan, or about 51 percent of China’s total mortgage portfolio.

“Instead of increasing sales, the removal of price floors could end up tanking property asset value and discouraging people from buying homes,” SinoInsider wrote.

“More ominous signs for the real estate sector emerged after the ‘Golden Week.’ On Oct. 9, a group of investors holding over $6 billion of Evergrande’s bonds in notional terms issued a statement urging the developer to get regulators to approve its scrapped restructuring deal. The investors note that Evergrande is on course to be wound up at a hearing on Oct. 30 without the deal, and ‘this will likely lead to the uncontrolled collapse of the group.’ A day later, Country Garden, which replaced Evergrande as the leading property company in China, warned in a filing with the Hong Kong stock exchange that it could default on some of its offshore bonds.”

According to SinoInsider, if the Xi leadership has judged that there is no avoiding a hard landing for the Chiense property sector, it would not fear the potential impact on consumer confidence that arresting Xu Jiayin would bring.

“Rather, Beijing now has a convenient scapegoat to blame for China’s property sector woes and could later issue propaganda casting the CCP authorities as the “savior” for moving against the culprits responsible for the crisis,” the analysts say.

Factional connection

As the economy continues to deteriorate, the case against Xu and other drastic moves by Beijing could also reflect an escalation in the intra-CCP struggle between Xi Jinping and rival forces in the regime.

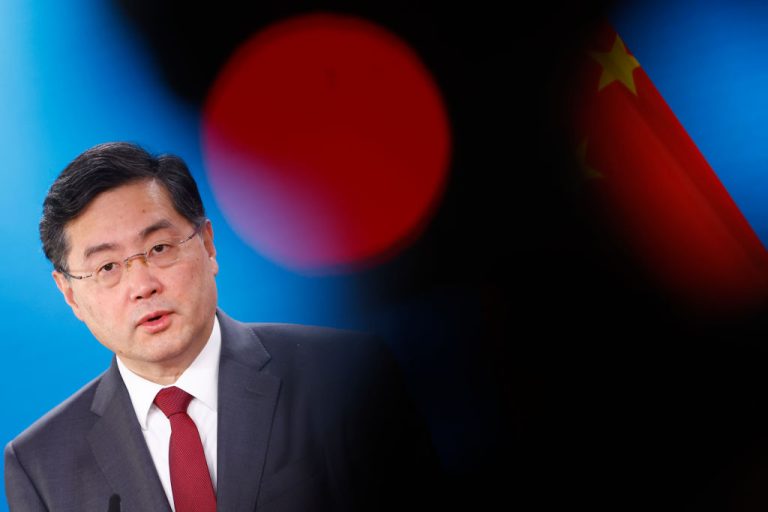

In particular, Xu Jiayin is “known to have close associations with Zeng Qinghong, the de facto head of the Jiang Zemin faction,” SinoInsider wrote.

Jiang, the former CCP leader, dominated Chinese politics from the late 1990s to 2012, when Xi Jinping took power and began sweeping purges of the Party-state establishment.

Evergrande saw great expansion in the southern province of Guangdong at a time when Jiang factionalist Zhang Dejiang was provincial CCP head. “Without the powerful political backing of Zhang, Zeng, and the Jiang faction, it seems unlikely that Evergrande would have been able to expand nationally in the 2000s and eventually make the Fortune 500 list in 2016.”

In analyzing recent purges in the Chinese foreign ministry and military, SinoInsider also believes the high-profile moves against Xu and Evergrande could be motivated by Xi’s desire to keep Zeng Qinghong in check.

Xi could suspect that “Zeng and others in the domestic ‘anti-Xi’ crowd were behind the developments that forced Xi to sideline his political allies like foreign minister Qin Gang and defense minister Li Shangfu,” which happened this summer and in September.

By taking down Xu and mounting corruption probes into Evergrande, the Xi leadership could be trying to pave the way for purging Zeng, reining in the remnant Jiang faction, and eventually denounce Jiang Zemin.

While such an outcome would be potentially destabilizing for the entire CCP given Jiang’s status as a former regime leader, Xi could take that risk if he finds himself and the Party unable to overcome the many crises plaguing China today.

“The probe of Hui Ka Yan and other Evergrande executives suggests that Beijing could allow Evergrande to declare bankruptcy and enter into liquidation. State-owned enterprises could be tasked to take over some of Evergrande’s more valuable assets and land, as well as handle the company’s unfinished projects,” SinoInsider wrote.

Meanwhile, “Evergrande and [Xu]’s downfall will almost certainly worsen China’s property sector crisis and the spread of financial contagion at a time when the CCP and Xi Jinping face crises on all fronts.”