Ancient Chinese copper coins were circular in shape with a square hole in the middle. For the ancients, the round shape symbolized the eternity of heaven, and the square hole in the middle symbolized the stability of the earth. The markings were: Heads for yang representing heaven, innate wisdom, and the basis of running a business and tails for yin representing the earth, relating to an individual’s character and integrity, and the foundation of establishing oneself.

The copper coins were very durable and signified longevity. Compared with silver and gold pieces used in ancient times, copper coins were in abundant supply. Being everywhere, just like heaven and earth the coins symbolized the ubiquitous influence of proper conduct necessary in sustaining life, business, and everything.

In Chinese culture, a water fountain can be understood to represent “money.” If a person cultivates wisdom and good character, “money” will flow to his business like a fountain.

1. Running a business with goodwill and preserving dignity

A long time ago a businessman named Qiao Zhiyong, lived in northern China, during the Qing dynasty. He found sponsors to start a tea business in the south during the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom period and he endeavored to restore the interrupted tea route. Qiao organized people in the south to transport the tea up north. He sent the tea to those who funded the operation. One day the tea store owner said to his employees, “Weigh the packages to make sure we weren’t cheated.” They weighed the packages and said happily, “Boss, each package weighs one catty (a traditional Chineseweight of around 600 grams) two taels (a traditional weight of 50 grams.)” Qiao had given two taels extra per catty. Delighted, the owner replied, “Great, hurry up and repack it into one-catty packages!” An old man who witnessed the operation said, “This is it. From now on, all the tea business will be now be called Qiaos!”

One year, there was a famine. Some people could not afford food, so they had to beg or receive handouts. It didn’t bother poor people to beg for food, but those who had some education or social status felt it was not dignified to do so. The Qiao family thoughtfully provided relief in the form of constructing a building. Anyone who helped move one brick got a meal. That way, it did not count as begging. They earned their food by helping with the construction. Qiao showed kindness in helping people preserve their dignity.

2. The golden rule in business–give a little extra

The ancient Chinese used a scale of sixteen taels. The first six taels represented the six stars of the southern Dipper, followed by the seven stars of the Northern Dipper. The Southern and Northern Dipper governed life and death respectively, implying that measuring weight is a matter of life and death. The last three taels represented the three deities of Fortune Wealth and Longevity.

These three were believed to be deities that monitored merchants. In measuring goods, if merchants withheld one tael, the deities would reduce their blessings. For two taels withheld, the three deities would reduce their wealth, and if the merchant shorted a person three taels, the deities would shorten his life. It thus became a practice for merchants in ancient China to give their customers something extra when weighing.

There is an ancient Chinese phrase “無尖不商 (Wú jiān bù shāng)” which means “Successful businessmen always give a bonus.”

In modern China, a phrase with the same pronunciation, but written in modern Chinese: “無奸不商 (wú jiān bù shāng),” means “Crooks take all the business,” implying businessmen have to be “crooked” to succeed.

In Asian stores and offices, one often sees shrines in the display, paying homage to the deities of wealth. Zhao Gongming is one such deity. This legendary figure started his business by selling grain. At the time, a cone-shaped “bucket” and a cylindrical “shen” were used to measure. A scraper was used to level the surface. When it was flat, the container was full. No more, no less.

When a scraper was not available, people used their palms to level the surface. Those who were cunning would press their palms down to reduce the amount of grain. Gracious and generous shopkeepers would arch their palms upward, thus leaving the container extra full. Zhao Gongming always practiced the latter. According to traditional wisdom, the shopkeeper who gives extra is a good merchant.

If a merchant earns a good reputation, his business will naturally grow and do well. Like grain merchants, cloth merchants also had a business motto. They would say 足尺放三 (Zú chǐ fàng sān), which means “give three extra inches for every meter measured.” The principle also applied to oil and vinegar. The merchant would add a bit more after the desired volume had been measured.

Giving customers a little extra was the golden rule for doing business in ancient China. People believed it to be the secret to success.

3. Money given away always returns

Fan Li was a strategist for the king of Yue during the Warring States period (771–476 B.C.). His book entitled “Business Lessons” was an ancient business classic. People later respected him as the Grand Master of Business and even as the deity of business management. Fan spent more than twenty years assisting the king of Yue to reinstate the Kingdom. After they accomplished that goal, Fan would not accept any reward. Instead, he retired from his esteemed position and left empty-handed for the state of Qi.

In the Qi Kingdom, Fan started a business from nothing and was very successful. The King of Qi employed him as a minister because he did so well. He later gave away all his money, returned the ministerial seal, and left again empty-handed. He relocated his family to the land of Tao, where he started his business from scratch again. He again accumulated a fortune which he gave away, a practice repeated three times in 19 years.

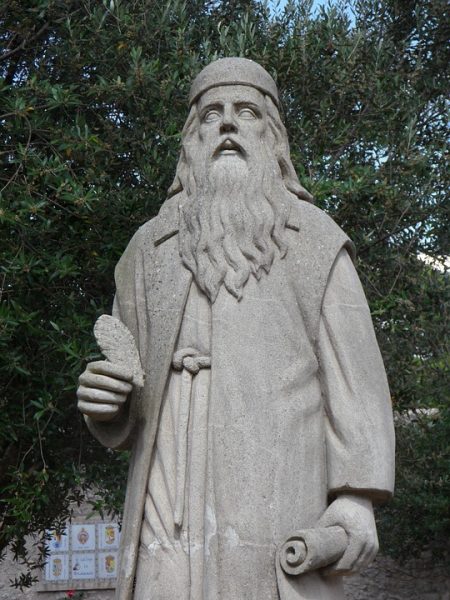

Li Bai

Li Bai, the most famous poet in Chinese history of the Tang Dynasty, wrote a poem, “One is born for a purpose; Money given away always returns.” It told the story of Fan Li. In his eyes, high rank and wealth were nonessentials, and could be given up.

Sang-ok, who lived in the 19th century and is remembered as the first Korean tycoon, did not leave any inheritance during his lifetime and donated all his wealth to the nation. Likewise, many Western tycoons and millionaires are philanthropists, and help the needy with the money they earn.

Fan Li’s reputation of benevolence and credibility spread all over China. In his later business dealings, wealthy families were willing to provide money to help him through financial crises. Once, Fan Li had difficulty in cash flow and borrowed 100,000 cash from a wealthy family.

A year later, the rich man went out to collect the debt with the IOUs. He accidentally dropped his purse into the river, losing both the IOUs and the money for the journey, so he went to Fan Li for help. Fan Li paid the man back with interest, and also gave him extra money for the journey. Fan Li’s moral and ethical business practice enabled him to share his wealth with the poor and distant relatives without being burdened by money.

4. Being generous and doing what is right

Wu Pengxiang was a grain merchant of the Qing Dynasty. One year, Wu signed a contract for the purchase of 800 Dou (equal to approximately 8,000 kg) of pepper.

Soon after receiving the goods, Wu’s employees discovered that the pepper was toxic. When the merchant learned of the situation, he asked to have the goods returned, terminate the contract, and refund the money.

Wu refused the merchant’s request. Instead of returning the goods and recovering the payment, Wu set the toxic pepper on fire and took a huge loss. When asked why, he said that if the merchant took the pepper back, he might sell it again, potentially poisoning many people.

One time, there was a severe drought in China and rice prices soared. Wu shipped tens of thousands of dan (one dan was about 100 kilograms) of rice from the south. In order to help the locals survive hard times, Wu did not raise the price but instead sold it at a low price.

Wu was like the nobleman that Confucius once described, “How could a nobleman be called a nobleman if he abandons benevolence and goodness? A nobleman does not deviate from benevolence no matter what. Even in the most pressing time, he must act according to benevolence, and the same is true when he is in turmoil.”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up