In World War II, Chinese forces were usually outmatched by their Japanese adversary in every way. But sometimes, leadership could make all the difference.

By early 1942, the Japanese military occupied much of China, nearly all of Southeast Asia, and was making rapid progress throughout the Pacific. Allied strategists looked for ways to bring down Japan, and looked to Burma, then a part of the British colonial empire in India.

Burma was seen as the key to establishing a supply route to the Republic of China, which was hard-pressed to hold out against superior Japanese forces, much less go on the offensive to drive them out. A road through Burma connecting with China’s southwest border would offer great aid to the Chinese defenders and hasten Japan’s defeat.

China had begun work on the so-called “Burma Road” as early as 1937, the year all-out hostilities with Japan began. However, following the raid on Pearl Harbor and Japan’s lightning advance, much of Burma also fell. The Japanese advanced with impressive speed; by May they would be at the Chinese border and cut off the Burma Road.

In April 1942, a 7,000-man British force found itself surrounded by a similar number of Japanese troops in Yenangyaung, central Burma. Led by commander Lt. Gen. William Slim, the defenders were able to demolish the oil fields in the area and deny them to the enemy. However, they had seemingly no way of escaping the encirclement.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

As the Japanese closed in, another party joined the fray.

The Chinese 113rd Regiment, part of the country’s expeditionary force in Burma, came to relieve the British. But their odds were unfavorable: the Regiment had just 1,100 personnel, of which just 800 were combat troops. By April 14, the British were running out of food and ammunition.

Despite the desperate situation, the Chinese force delivered a heavy blow against the Japanese 33rd Division, which outnumbered them more than eight-to-one. Hundreds of Japanese were killed in action, and the British force was able to retreat safely.

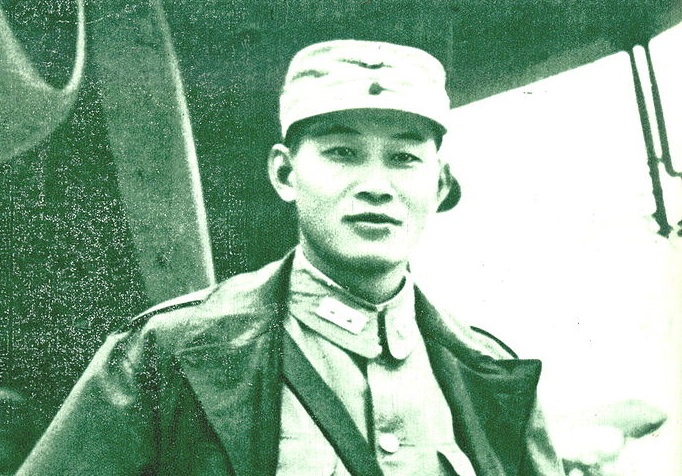

The commander of the 113rd Regiment was Gen. Sun Liren, a man who would come to earn the nickname “Rommel of the East,” after the daring and principled German general, as well as the moniker “Jungle Fox.”

From ‘taxation corps’ to national hero

Sun had wanted to bring an entire Chinese division — the 38th — to bear against the Japanese; however, his superior, Gen. Luo Zhuoying, had refused. Undeterred, Sun sent small units to harass the enemy, disorienting them badly. After that, the Chinese troops attacked the Japanese all at once, pushing them back and taking a key position. A Chinese battalion commander was killed in the fighting. More than 500 British prisoners of war, including missionaries and journalists, were rescued from captivity.

The victory at Yenangyaung was a rare win for the Allies in the early stages of the Pacific War — the name for World War II in Asia after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Sun Liren would go on to score more triumphs in the China-India-Burma theater, playing a key role in eventually driving out the Japanese military from Burma and opening the Burma Road.

Born in eastern China to an intellectual family, Sun’s father forbade him from studying military science. Instead, as a young man, Sun travelled to Purdue to major in civil engineering.

But upon completing his studies at Purdue at the age of 25, Sun applied for the Virginia Military Institute. He graduated in 1927, armed with knowledge that would set him apart in the campaigns yet to come.

China at the time was divided between numerous warlord factions, most claiming to be the nation’s true leader. As Sun’s father was an official in the former imperial government, Sun could have joined his provincial military faction and landed a high post. Instead, he decided to enter the armed forces of the Nationalist government, which was still comparatively weak, and start his career at the bottom.

Sun was first assigned to the Military Police Instructional Corps in 1930, quicking becoming a major in command of a battalion. The effectiveness of his training earned him praise from Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Chinese republic. He was transferred to the General Corps of Taxation and Police, where he was given the rank of colonel. In 1933 he served with distinction against the communist rebellion in southern China. His “tax police” regiment (about 1,000 men) quickly became famous, as Sun regularly accomplished missions that were considered challenging even for a division (roughly 10,000 men, though Chinese divisions of the time were often much smaller) to take on.

Fighting the Japanese in China and Burma

While the war in Europe began in 1939 with the German invasion of Poland, China had already been battling Japan since 1937, losing millions of people, cities, and industry as the well-armed and well-disciplined Imperial Japanese Army swept aside the Chinese with their terrible coordination and hopelessly obsolete weaponry.

The first major battle of the war was fought at Shanghai, where Sun Liren personally entered combat and took part in seven assaults on the enemy. While leading a charge, Sun was severely wounded, being hit by 13 pieces of shrapnel.

From Shanghai, the Japanese advanced to Nanjing, taking the Chinese capital in a frenzy of mass murder and rape. In 1938, a massive battle at Wuhan saw over 1 million Chinese casualties; the city was lost, but the Imperial Army did not have the strength to advance further.

As one of the few experienced officers left in the Chinese army after its repeated defeats, Sun Liren was assigned to southwestern China to train green troops. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, there was new hope of collaboration between China and the Western Allies. Sun was placed in charge of the 38th Division, and deployed to Burma.

In August 1942, after the British retreat to India, Sun’s forces were re-assigned to the Chinese Army in India, and received American training and arms. In the Burma Campaign, Sun’s 38th Division led an attack into the Hukang River Valley. He encountered and defeated the elite Japanese 18th Division — known as the “king of jungle warfare.” In another engagement a couple months later, the 38th Division defeated a force seven times its size.

Sun earned great respect from British and American counterparts, and even the Japanese feared him as the “god of war.”

In addition to his skill as a military leader, Sun Liren also had access to tanks, a weapon almost completely unavailable to other Chinese commanders. The machines were supplied by the Americans, as the Chinese did not have the capability to construct their own when the war with Japan broke out. This inspired the comparison between Sun and the German general Erwin Rommel, who often spearheaded German panzer offensives in the French and African battlefields.

Years of harsh fighting paid off in 1945, when the Japanese were completely dislodged from their positions and the Burma Road finally reopened. However, by that point the war in the Pacific was already nearing its end.

Sadly, Sun Liren’s defeat would not come at the hands of a foreign enemy. After World War II, the civil war between the Nationalists and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) reignited. While Sun defeated many communist units in the northeastern provinces and other regions, factional struggles in the Nationalist forces led to Sun’s demotion at a critical period in the war.

The Nationalists were defeated and forced to Taiwan, where the Republic of China still exists today. In 1954, Sun was accused of a U.S. plot to overthrow President Chiang and put under house arrest, a charge lifted only in the late 1980s. He passed away in 1990, shortly prior to his 90th birthday.