The “Standards for Being a Good Student and Child” (Di Zi Gui, 弟子規) is a traditional Chinese textbook for children that teaches morals and proper etiquette. It was written by Li Yuxiu in the Qing Dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Kang Xi (1661-1722). In this series, we present some ancient Chinese stories that exemplify the valuable lessons from the Di Zi Gui. The second chapter of the Di Zi Gui instructs readers to fulfill their duties as siblings and when with their elders.

Read the previous installment here.

It is stated in the Di Zi Gui:

稱尊長 勿呼名

對尊長 勿見能

When addressing an elder

Do not use his personal name

When before an elder

Do not show off your talents

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Aside from requiring goodwill among siblings, and the use of proper salutations when speaking with elders, an important aspect of traditional Chinese etiquette is modesty.

An ancient calligrapher from the Jin Dynasty, and Han Dynasty founding hero Zhang Liang famously respected their elders in their youth. They learned to be humble and hence acquired knowledge and skills from their elders.

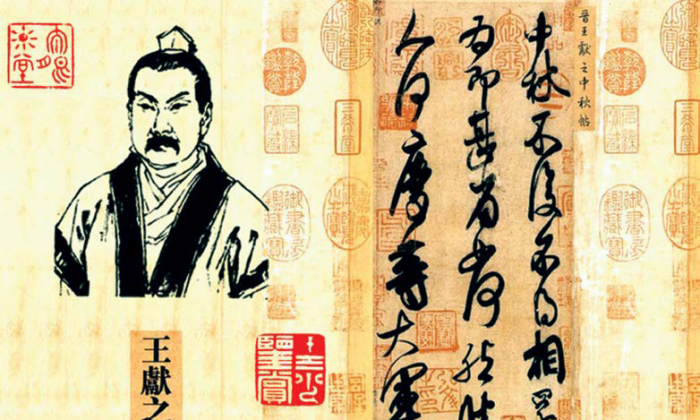

Renowned calligrapher Wang Xizhi, known as the Sage of Calligraphy in China, lived during the Jin Dynasty (303–361 A.D.) and had seven children, among whom his youngest son, Wang Xianzhi, (344–386) was also a distinguished calligrapher.

By the time Xianzhi was 15 years old, he had already achieved a great level of skill in calligraphy and often received praise from his father and other elders. Xianzhi hence became arrogant and lazy, thinking that his ability was already excellent and that he no longer needed to put in the effort to work hard and improve himself.

There is a story about how Wang Xizhi helped his son realize the foolishness of his arrogance and understand the importance of diligence. One day, Wang Xizhi was summoned to the capital and to bid him farewell, his family held a lavish dinner. Fine food and wine were served at the feast. While slightly intoxicated, Wang Xizhi had a sudden inspiration to write some words of wisdom as guidance for Xianzhi.

Wang Xizhi wrote a poem on the wall called “Precepts Against Arrogance” (戒驕詩), advising Xianzhi not to be arrogant but to work hard. Xianzhi, however, was not entirely convinced. He copied the poem dozens of times each day, and just before his father returned home, he erased his father’s words when no one was looking and rewrote it in the same location on the wall, imitating his father’s calligraphy.

Xianzhi was very proud of himself. In his arrogance, he thought his calligraphy was just as good as his father’s and that no one would be able to tell the difference.

When Wang Xizhi came home, he looked intently at the poem on the wall for a long time, then scratched his head and sighed.”Could I have drunk too much wine that night, to have written such clumsy characters?” he exclaimed.

Xianzhi instantly reddened with embarrassment, finally realizing that only through diligent study and hard work could he eventually become a renowned calligrapher like his father.

Zhang Liang and the shoes of the old sage

Zhang Liang (c. 262–189 B.C.), courtesy name Zhifang, was born in the State of Han (located around what is now central Henan Province). In order to avoid the chaos of war, his family moved to Nanyang in Henan and then moved to the Pei Kingdom. Later on, he settled down in Pei Kingdom and became a citizen there.

In Zhang Liang’s childhood, on a windy, snowy winter day, he happened upon Yishui Bridge in the town of Xiapi. There he met an old man wearing a yellow shirt and a black hood. The old man threw one of his shoes down to the bridge on purpose and told him:

“Little boy, please go to pick my shoe back up for me.” Zhang did not hesitate. Regardless of the danger of slipping into the river and being exposed to the cold wind, he went down to the bridge and picked up the shoe for the old man. The old man did not take the shoe, but offered his foot to Zhang and asked him to put the shoe on for him. Zhang did not mind and respectfully did what the old man told him to do. The old man smiled and said: “Boy, I see much promise in you. Come here tomorrow morning and I will teach you some things.”

The next day, before the crack of dawn, Zhang Liang came to the bridge and saw that the old man was already there. The old man said: “You came here later than me. I cannot teach you the Tao today.”

The next day, Zhang got up even earlier. Still, the old man was there before him, and he gave him the same answer.

The third time, Zhang finally got to the bridge earlier than the old man. The old man then gave Zhang a book and said: “When you fully understand this book, you will be able to serve as the chief military counselor for a king in the future. If you need my help in the future, come to see me. I am the Yellow Stone at the foot of Gucheng Mountain.”

Zhang Liang went back home and he studied the book very carefully. Finally he mastered its essence. He was able to understand all of its intricacy and became very familiar with military tactics. Later, he assisted Liu Bang, first emperor of the Han Dynasty, in his quest to unite China.

Read the next installment here.