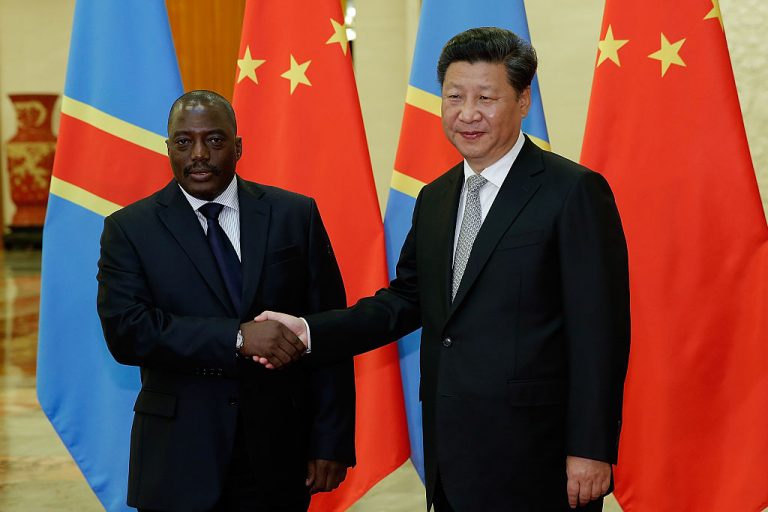

With 73 percent of its population living in extreme poverty, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Its deep-rooted corruption continues to worsen the problem. An exposé by Bloomberg has revealed how former president Joseph Kabila and his associates have essentially looted the country.

At the core of the scandal is a Chinese-run company and the BGFIBank Group. A leak of 3.5 million bank documents showed millions of dollars flowing through Congo Construction Co. (CCC) accounts to individuals and firms closely linked to Kabila. The funds went into the bank managed by his brother, Selemani Francis Mtwale, and partly owned by his sister.

In July 2018, Yvon Douhore, head of an in-house audit team in Kinshasa, noted that an account had been emptied after a Chinese businessman walked away with tens of thousands of dollars despite clear orders to prevent it.

Accounts held by the businessman’s firm, CCC, were frozen the previous month because the client file lacked important documents, BGFIBank’s compliance department records revealed. A history of transactions analyzed by Bloomberg found that political connections complicated the matter.

Opening the door to Chinese mining

After Selemani was removed as CEO in May 2018, the accounts were blocked by Douhore’s colleagues while an investigation was conducted into Selemani’s tenure. However, transactions were still being permitted by somebody at the bank, up until the final cash out of $2.5 million in July 2018. Douhore found out from the documents that it was the final act of the CCC’s undercover role as mediator between the Chinese mining companies and the Kabila clan.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa, a Paris-based anti-corruption group and the French news organization Mediapart obtained data covering nearly a decade of transactions at BGFI. They shared it with media outlets coordinated by the European Investigative Collaborations network and other NGOs.

Called “Congo Hold-up,” the consortium’s assessment reveals how the bank was exploited by the country’s most powerful family to fulfill its personal interests. At least $138 million of public money was channeled to Kabila and his associates. It also unravels the hidden tactics used by Chinese companies to take control over the abundant mineral resources of the country.

The DRC’s vast reserves of cobalt and copper were opened to international investors when Kabila came to power in 2001. After western firms, which initially showed interest, began to pull out, it left the door open to communist China. The communist regime was eager to lay its hands on the two metals required in the production of electric vehicles.

In less than 10 years, Chinese companies have gone on to become major players, contributing to nearly 70 percent of Congo’s copper output and half of its cobalt production. At the core of this development is a $6.2 billion minerals-for-infrastructure deal, the largest investment in Congo’s history. It was initiated by the China Railway Group Ltd. and Power Construction Corp. of China, known as Powerchina.

In 2008, the two nations decided that the Chinese firms would fund infrastructure worth $3 billion and build a $3.2 billion copper and cobalt project called Sicomines. The profits from these two ventures, which were exempt from taxes, would recoup both investments.

A subsidiary of China Railway also won a no-bid contract from the Congo government to fix and manage the road from the mining epicenter of Lubumbashi to the border with Zambia. The project was also funded by tolls. With the concession fee of $300 for a round trip, it is one of the most profitable routes in Africa, having generated a total of $302 million between 2010 and 2020.

To monitor the Chinese relationship, Kabila established an agency, the Bureau de Coordination et de Suivi du Programme Sino-Congolais. He also appointed Moise Ekanga, an aide, to run it. The company, Strategic Projects and Investments (SPI), benefited greatly from the growing presence of communist China in Congo.

SPI held a 40 percent share in the toll road business until 2015 before taking it over completely. An audit by an anti-corruption firm under the ruling government states that the toll company has embezzled nearly $121 million since the exit of China Railway six years ago.

How much SPI paid China Railway to take over the toll company is not known. No payment was noted in the minutes of a board meeting assenting the share transfer. However, there are indications that some of the funds were sent to CCC. BGFI records show that from June 2013 to January 2016, the toll business made 41 transfers to CCC worth $7.8 million, most of which was removed in cash.

The owner of CCC was a Chinese man named Du Wei. He worked in Sicomines until 2012 before becoming a consultant for Kabila’s China agency. He incorporated CCC in the same year along with Guy Loando, a Congolese lawyer, and set up a corporate account at BGFI.

CCC, which had no projects between February and July 2013, received $18 million from bank accounts in China and Hong Kong held by four offshore firms incorporated in the British Virgin Islands. Another $1 million was transferred to CCC by the toll road company in June that year. Documents revealed that most of the $19 million were sent by Du to Kabila’s China agency not through direct transfers but via a sequence of cash withdrawals and deposits.

Ekanga then settled a $14-million loan his office had secured from BGFI for the benefit of companies that would be or were linked to Kabila. Half of the borrowed funds were wired by the agency to another BGFI account that forwarded the same amount to a cattle business Kabila planned to acquire. Bank records also show a $6 million transfer to a building firm owned by two allies of Kabila.

Between June and September 2016, Sicomines made three large payments to CCC totaling $25 million. Most of the funds were allocated by Du to the companies and individuals connected with Kabila’s family. BGFI records revealed that more than $1.7 million was wired by CCC to Du’s private accounts in Congo and Hong Kong.

Sicomines, which entered production in 2015, needed a proper supply of electricity to reach its full capacity of 250,000 metric tons of copper a year. Constructing a dam near the village of Busanga was therefore suggested. Initially, the $600 million project was meant to be part of the minerals-for-infrastructure deal.

However, in July 2016, China Railway and Powerchina founded a new company with Congo’s state-owned miner Gecamines that would control the 240-megawatt hydropower plant. At the time, 15 percent of the state’s share went to Congo Management Sarl, or Coman, a formerly unknown entity. Financial transactions that seemed to mirror each other appeared in the accounts of Coman and CCC, indicating the company had ties with Kabila’s aides.

In March 2017, Du began reorganizing CCC, with the company acquiring a phosphate mining permit owned by Allamanda Trading Ltd. Du then procured the 20 percent stake in CCC owned by Loando and moved all the company’s shares to an entity registered in the British Virgin Islands.

In January 2018, China Molybdenum Co. paid $40 million to acquire CCC and its phosphate license. When queried about whether CCC paid Allamanda for the permit or if any member of the Kabila family was a beneficiary of the firm, none of the parties involved responded.

Du continued to control CCC’s accounts even after its takeover by China Moly. A company partly managed by Kabila’s sister and sister-in-law transferred $7.7 million to CCC in May 2018. In the same month, $1.9 million was wired to CCC from a BGFI account belonging to Congo’s central bank.

In May 2018, $1.5 million was transferred by Du to a company in the United Arab Emirates, before he and another person withdrew the rest of the amount in cash. Between January 2013 and July 2018, $65 million passed through CCC’s accounts; $41 million was withdrawn in cash, making it extremely hard to trace the beneficiaries of all the funds.

Douhore’s audit, which ended in July 2018, established that governance had been “unacceptable” and was marked by a “lack of integrity and transparency in the declaration of conflicts of interest.” Transactions in millions of dollars were conducted in and out of CCC’s accounts without necessary paperwork or with valid documents, the audit revealed.