News analysis

Early in the morning of Feb. 24, the Russian Federation launched a “special military operation” on multiple fronts across Ukraine, escalating a frozen conflict that began in 2014 to a full-scale invasion. The war has seen thousands killed, threatened Ukraine’s existence as an independent nation, and led the U.S. and its allies worldwide to impose swift and massive sanctions on Russia.

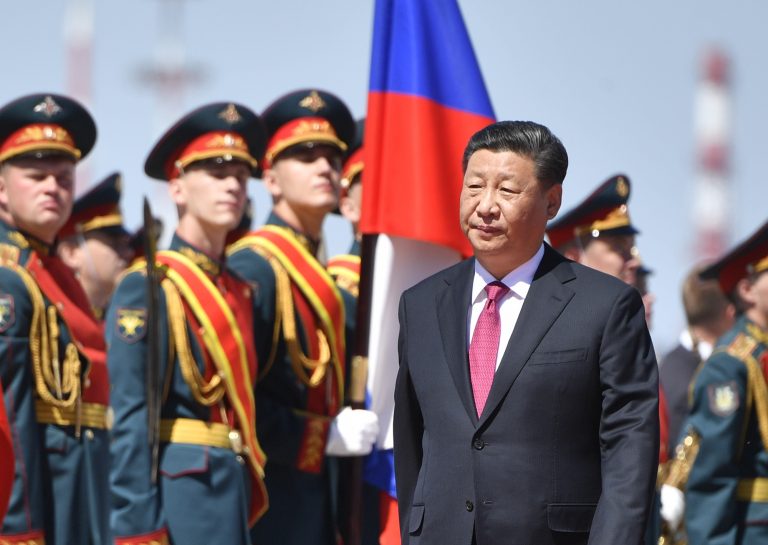

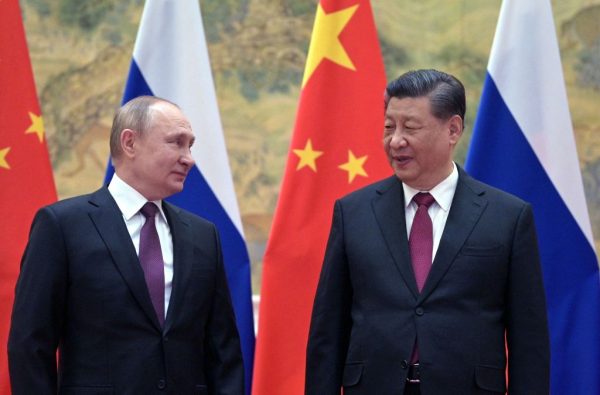

The biggest war in Europe since World War II has, not surprisingly, many heads turning east at Russia’s most powerful partner, the People’s Republic of China (PRC). On Feb. 4, Russian President Vladimir Putin met with Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping at the beginning of the controversy-ridden Winter Olympics, where the two signed a joint statement promising “no-limits” friendship and “no forbidden areas of cooperation” between Moscow and Beijing. Speculation abounds that Putin delayed his invasion so as not to rain on Xi’s Olympic Games parade.

In the face of sweeping Western sanctions and diplomatic repercussions taken to isolate Russia, Chinese support has naturally become crucial if the Kremlin is to weather the storm. So far, Beijing has obliged. The PRC has not condemned Moscow’s invasion, and abstained in several U.N. actions concerning the conflict. On the day of the invasion, China lifted all import restrictions on Russian wheat. And China has declined to join in on sanctions.

On March 2, China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission chairman Guo Shuqing said, “As far as financial sanctions are concerned, we do not approve of these, especially the unilaterally launched sanctions because they do not work well and have no legal grounds.”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine — and the almost eight years of low-level warfare that preceded it — came about as the result of complex international and historical factors. But one result of the new Iron Curtain descending across Europe is simple: Russia will be unavoidably and increasingly thrust into China’s economic and geopolitical orbit, regardless of whether Putin prevails in his effort to subdue Ukraine.

Closer to China

READ MORE:

- As Challenges Mount, China’s Xi Calls for ‘Self-Revolution’

- In Leaked Recording, Elite Chinese Scholar Laments Crippling Dysfunction of Communist Regime

- In 2022, Expect China’s Economy to Worsen Further

Though boasting vast natural resources and the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, Russia is a power in unmistakeable decline. Its recovery from the post-Soviet chaos of the 1990s was short-lived, and the 2014 annexation of Crimea was the beginning of the end for hopes of amicable cooperation with the West. Demographically, Russia is also struggling, with dismal birthrates brought about by economic hardship and social malaise.

China is Russia’s largest trading partner, buying vast quantities of gas, oil, and grain from its northern neighbor. It also dwarfs Russia economically and would exert great influence on Moscow in any close relationship. Russia’s entire 2021 GDP of US$1.77 trillion was smaller than that of Jiangsu, an eastern Chinese province near Shanghai that has a gross economic output of $1.804 trillion.

And as Russia is increasingly cut off from Western financial vehicles, it may turn to Chinese yuan as well as cryptocurrency and other alternative means of keeping trade and business alive.

Diplomatically, the confrontational stance between Moscow, the U.S., and its allies could also be exploited by Beijing. As Putin threatens nuclear war to stave off what the Kremlin has long regarded as unacceptable NATO overreach into Ukraine and other countries in the former Soviet Union, Russia will attract only more ire from upholders of the “international rules-based order” — countries that seem lukewarm about seriously confronting or meting out punishment to the much more powerful China.

All this would seem to play into the hands of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). On the one hand, Moscow — with or without Ukraine subjugated — becomes more dependent on Beijing’s good graces in lieu of exchanges with the West. At the same time, opportunistic fixation on Russia’s misdeeds makes China appear the more rational actor, similar in nature (if not in degree) to how Stalinist North Korea, with its missile tests and nuclear detonations, is perceived to be the unhinged rogue state of which even its ally the PRC is embarrassed.

The CCP is known for working with autocratic regimes and democracies alike to expand its international influence, an effort most famously encapsulated by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It has also infamously bought or stolen trillions of dollars’ worth of foreign technology not just to build the Chinese tech industry and infrastructure, but also for nefarious applications such as AI-assisted mass surveillance and internet censorship. The “China model” is then exported to other regimes, propping up those governments and making them effective clients of the PRC.

It may be seen that the recent tensions, egged on by NATO and which ultimately led to war between Russia and Ukraine, have the ultimate effect of benefitting a much more serious adversary of the “rules-based” order familiar to the West — Communist China.

Quite possibly, a new situation is emerging that may be to Beijing’s geopolitical advantage. But there are also many challenges to be faced by the CCP and Xi Jinping.

Belt and Road in jeopardy

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is almost certainly going to be a double-edged sword for China, especially in the short term.

Analysts at SinoInsider, a New York-based political risk consultancy, wrote in a March 3 newsletter that “While Russia would likely become even more economically reliant on and align itself closer to the PRC, increased Russian demand and dependency alone will not give Beijing what it needs to offset the global economic impact of the invasion.”

Ukraine is also the site of many Chinese investments, such as in Ukraine’s powerful agricultural industry, that could be impacted by the war and for years to come.

The overland segment of the BRI runs through Ukraine on its way from China through Russia to Europe. Western sanctions on Russia throw a wrench in this route, meaning billions in wasted Chinese money. Eastern Europe is also home to many countries, most vocally the small Baltic states, that have taken issue with Beijing’s hegemonic attitude — especially with regards to support for Taiwan, an island claimed by the PRC.

Already negatively predisposed to the CCP, these countries may clammer for sanctions against China, citing its relationship with the Russian pariah. Other Western governments could also levy sanctions against Beijing should its “strategic partnership” with Russia drag the PRC into the “new cold war.”

In 2021, the PRC’s trade surplus with the 27 EU countries was $208.4 billion, a year-on-year increase of 57.4 percent. The healthy PRC-EU trade relationship, which grew during the Sino-U.S. trade war years as Beijing sought to counter Washington’s sanctions, could be in jeopardy moving forward.

Dangers for Xi

While a closer partnership between Russia and China looks good on paper — China has manufacturing and manpower matched by Russia’s abundant natural resources — both countries’ demographics are in decline, neither are true technological powerhouses, and both are strongly influenced by the communist bent of authoritarian rule that is not conducive to sustainable long-term growth or efficient governance and social trust.

For Xi, there is another danger. Should Putin find success subduing Ukraine in a timely fashion, anti-Xi factions in the CCP could use the Russian example as a means of putting political pressure on the Chinese leader to expedite the “reunification” of Taiwan with the mainland through force of arms.

READ MORE:

- Russian Invasion of Ukraine Casts an Ominous Shadow Over Taiwan

- Does the CCP’s New ‘Historical Resolution’ Give Xi More Power? Not Really.

Xi, who has little in the way of diplomatic or economic accomplishments to show for his decade in power (China’s economy has been slowing precipitously, and events such as the Hong Kong protests, Uyghur persecution, and coronavirus pandemic have tarnished Beijing’s reputation), is already facing pushback from the Party elite over his determination to take a third term as CCP head at the upcoming 20th Party Congress.

In order to secure this third term, Xi could be tempted into an invasion of Taiwan — one which, without lengthy preparations and ample experience fighting previous wars, would lead to disaster for Xi‘s political future. Yet should the Chinese leader resist this dangerous urge, he would have to find another way to handle the opposition amidst the challenging international environment created by the war in Europe, potentially leading to Black Swans for the communist regime.