News analysis

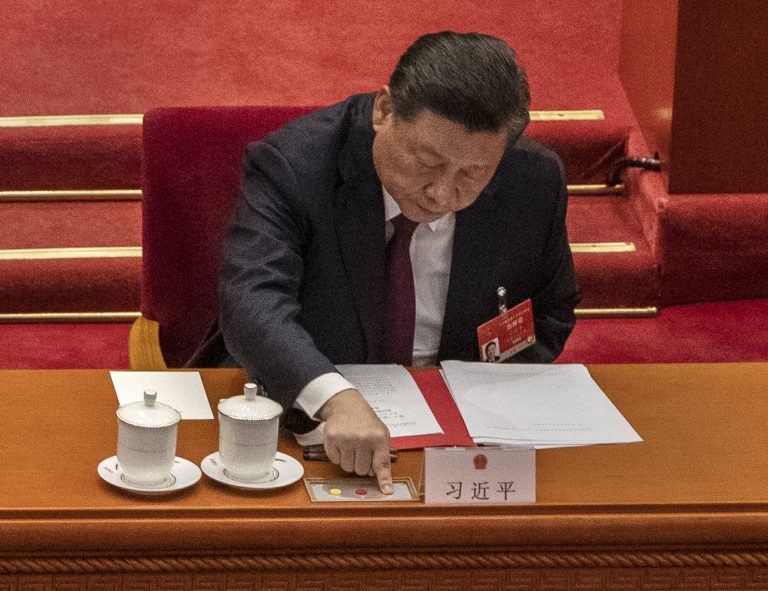

The adoption of a “historical resolution” by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership has been widely touted in the international media as a major political triumph for General Secretary Xi Jinping as he prepares to rule China for another five years.

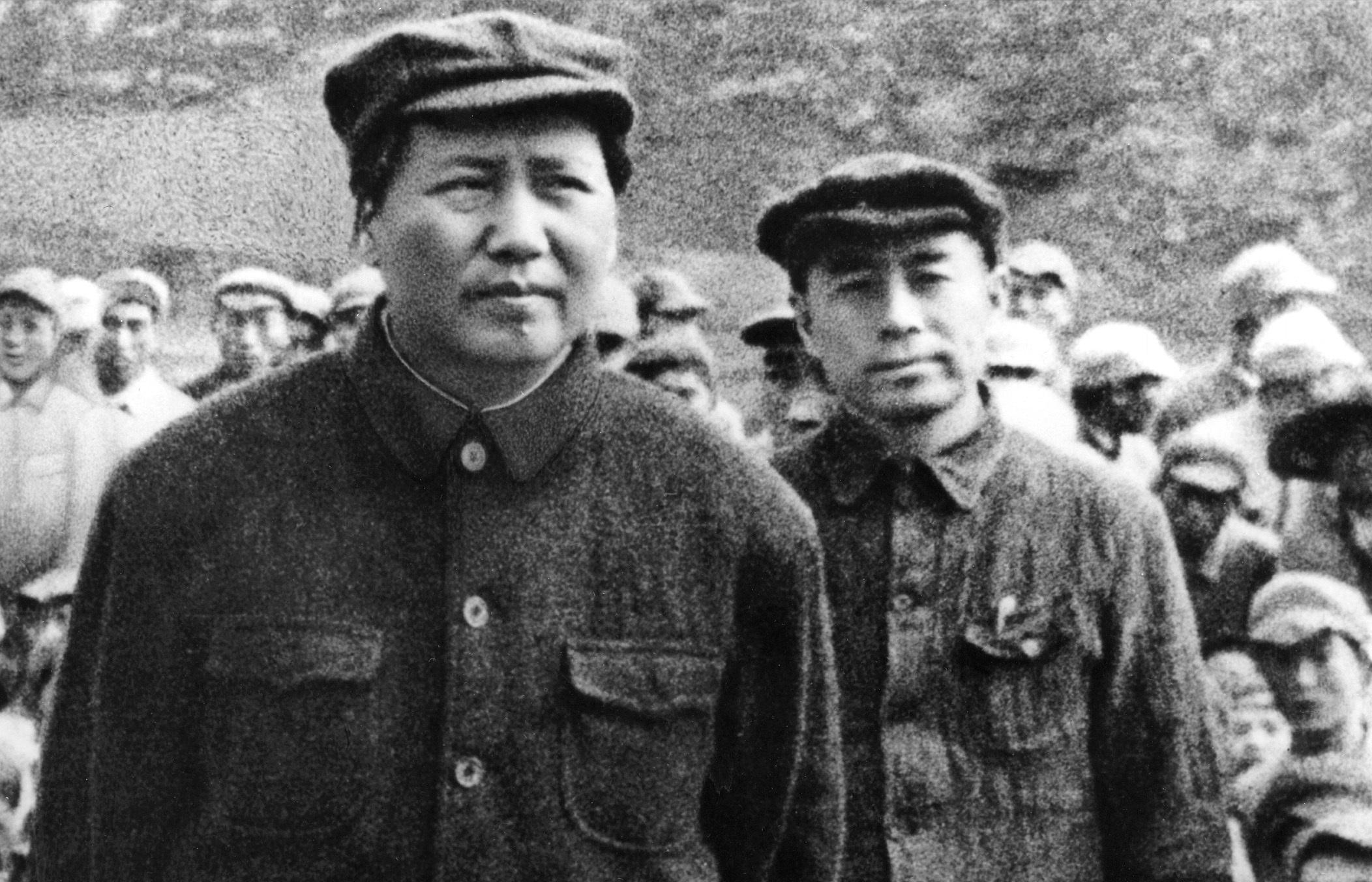

China watchers have widely compared the document with the just two other resolutions issued in the CCP’s 100 years of existence. Mao Zedong, who promulgated the Party’s first historical resolution in 1945, led the communist movement to victory in the Chinese civil war four years later, founding the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The second historical resolution came in 1981, two years after leader Deng Xiaoping launched the economic “reform and opening up.”

The communique from the recent Sixth Plenum of the CCP’s 19th Central Committee, which concluded on Nov. 11, indicates that the third historical resolution, titled Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century, will summarize the accomplishments of the CCP since its founding in 1921. It will also stress the roles that successive leaders’ official interpretations of Marxist ideology played in the regime’s development and survival.

In particular, the resolution is to focus on the importance of “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” the current Chinese leader’s doctrine. According to the communique, Xi led China in “new and significant achievements,” despite the impact of the novel coronavirus pandemic and “worldwide changes of a scale unseen in a century.”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Xi has run a sweeping anti-corruption campaign for nearly the entirety of his time in office, and in recent years has presided over the intensification of authoritarian policies and ideology. His rule being of “decisive significance” for China, the communique called upon the country to uphold “Comrade Xi Jinping’s core position in Party Central and in the Party as a whole.”

On par with Mao and Deng?

Major media outlets were quick to describe the Resolution as cementing Xi’s eminent position in the CCP. Christian Shepherd of the Washington Post said that the document secures “Xi’s iron grip as he prepares for a near-inevitable third term that would extend his rule until at least 2027.”

In a piece titled “China’s Xi Jinping Remakes the Communist Party’s History in His Image,” The New York Times’ Chris Buckley wrote that the move “elevated Mr. Xi to a stature alongside” Mao and Deng. “The strong endorsement of Mr. Xi’s policies could become powerful political currency for him” as he aims to secure a third term as Party head at the 20th CCP National Congress next year.

Tony Saich, a China-focused academic at Harvard University, told the Washington Post that “this resolution is geared to say that the party desperately wants Xi to stay on, will plead with him to stay on, because he is the leader to take China forward.”

By passing the resolution, Xi demonstrates the ability to rewrite the official history of the Party and be “an architect of his own epoch,” Shepherd wrote.

However, the circumstances of the recent historical resolution are markedly different from those passed in 1981 and 1945. Despite the adulations and titles lavished upon him, Xi faces unique challenges to his rule — often from within the regime itself — that complicate his leadership and could jeopardize the Party’s future.

Mao Zedong, who became head of the communist movement in the 1930s, consolidated power through the Yan’an Rectification Movement (1942–1945) — a fanatical political inquisition carried out in the caves of the Communist Party’s wartime redoubt in northwest China. The Movement, which featured repeated indoctrination in Mao’s ideas and severe punishment for even slight dissent, eliminated those within the CCP who advocated a more internationalist approach to communism and closer cooperation with the Soviet Union.

“Mao’s 1945 historical resolution came after he seized power and was a criticism of the ‘incorrect line’ of his predecessors,” Don Tse, lead researcher at New York-based political risk consultancy SinoInsider, told Vision Times.

Deng Xiaoping, one of the key cadres in the Party’s early history, fell into disgrace during the 1960s when he was lumped in with ill-fated PRC head of state Liu Shaoqi as a “capitalist-roader.” Unlike Liu, however, Deng survived the trauma of Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when millions accused of straying from socialism were humiliated, brutalized, or driven to suicide. Following Mao’s death in 1976, Deng prevailed over Hua Guofeng, the Party chairman whose “Two Whatevers” upholding the policies of the communist state’s late founder proved deeply unpopular with the bulk of CCP functionaires.

Initial economic reforms announced by Deng in 1979 united the Party behind him, and his 1981 historical resolution addressing “certain problems in the history of our party” since the PRC’s founding repudiated the Cultural Revolution, while affirming the reform policies that would propel China to become the world’s second-largest economy.

Tse notes that while the third Communist Party historical resolution heavily promotes Xi Jinping Thought, it does not contain the criticism of predecessors or their political doctrines that is prominent in the previous resolutions.

“Rather than denying the legacy of previous leaders, Xi Jinping’s resolution acknowledges them as part of the century-long effort to ‘Sinicize’ Marxism,” he said.

This agrees with an observation made in October — when news that the Party would deliberate a historical resolution during the Sixth Plenum was announced — by South China Morning Post columnist Wang Xiangwei, who said that the document would likely be “forward looking about Xi’s era,” rather than criticizing “past major mistakes and lessons.”

Larry Ong, a SinoInsider analyst, told The Epoch Times in October that unlike Mao and Deng, who deployed their resolutions to “declare victory over their vanquished factional rivals and affirm the ‘correctness’ of their policies,” Xi “has yet to best” his foes in the CCP.

Factional struggle

The anti-corruption campaign under Xi that began shortly after he assumed office in late 2012 is regarded as an action directed against the entrenched influence of former Communist Party head Jiang Zemin — whose faction dominated Chinese politics following the death of Deng in 1997 and remains a potent force in the regime even today.

Hundreds of senior Party cadres taken down by the CCP’s disciplinary inspection commission were close allies of the now 95-year-old Jiang, or associated with those in his network of patronage. Prominent “big tigers” sentenced in Xi’s first term include Bo Xilai, the CCP boss of southwestern Chinese megacity Chongqing whose downfall was widely seen by overseas Chinese observers to be behind a failed coup against the incoming Xi; Zhou Yongkang, the retired security czar and member of the seven-man Politburo Standing Committee (PbSC) that runs the Party; as well as People’s Liberation Army (PLA) generals Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong. All had careers linking them directly to Jiang, a leader notorious for riding off of China’s economic success to line the pockets of his supporters.

Removing these “tigers” weakened, but did not defeat the Jiang faction, which retained several affiliates on the PbSC until 2017; important retired cadres associated with Jiang, such as China’s former vice president Zeng Qinghong, still have de facto authority on account of their prestige and personal connections.

According to SinoInsider’s Don Tse, the Jiang faction has repeatedly undermined Xi’s leadership, and even mounted a second coup attempt against him ahead of the 19th CCP National Congress in 2017.

Officials connected to Jiang continue to fall, even nine years after Xi’s ascension to power. On Nov. 5, former vice-minister of public security Sun Lijun was arrested following his Sept. 30 expulsion from the CCP and his post for political crimes, including “organizing gangs” to control “key departments” and going against the will of the Xi leadership.

Fu Zhenghua, who had held the same post as Sun and was PRC justice minister from 2018 to 2020, was purged on Oct. 2; both Sun and Fu had also served as leading cadres of the “610 Office” the informal name of a powerful Party organization created by Jiang Zemin in 1999 to carry out the repression of Falun Gong and other banned faiths.

So many security officials who worked in the 610 Office have been purged that according to some observers, a Chinese official’s risk of running afoul of Beijing can be rather accurately assessed by tracking his or her involvement in the persecution of Falun Gong — a campaign started and heavily promoted by Jiang.

Securing a third term

Despite the intense rivalry between Xi and Jiang, the Sixth Plenum communique does not offer a repudiation of Jiang’s political legacy or criticize the former leader. Instead, it includes Jiang as a “comrade” who upheld “the Party’s basic theory and line” through the “Three Represents” doctrine.

Willy Wo-Lap Lam, an analyst with the Jamestown Foundation, cited U.S.-based Chinese scholar and dissent Chen Pokong as saying that Xi was not unopposed in his efforts at cementing a cult of personality.

“This helps to explain why one relatively long paragraph in the communique on the Resolution is devoted to the policies of ex-presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao [Jiang’s successor],” Lam said, noting that the inclusion of their ideological contributions could be an unavoidable “concession” on Xi’s part.

Yet editorials published in the Chinese state media prior to and during the Sixth Plenum not only argue that Xi’s continued rule is necessary for the survival of “the Party and the country,” but also contain veiled criticism of the Jiang faction.

A Nov. 8 piece run by Xinhua New Agency focusing on the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” mentions Xi 77 times, Mao six times, and Deng twice, but omits Jiang and Hu entirely. Moreover, the article claims that Xi’s anti-corruption campaign “saved the day” following the “extremely bad and alarming political implications” of graft left unchecked.

The next day, People’s Daily published a similar editorial presenting Xi as a leader of the people willing to “do what we must do and offend the people we must offend.” This piece stressed the importance of anti-corruption, singling out the close allies of Jiang who had been purged before the 19th Party Congress: “Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai, Guo Boxiong, Xu Caihou, Sun Zhengcai, and Ling Jihua.”

Both articles railed against “iron-cap princes,” which, according to a recent analysis by SinoInsider, refers obliquely to Zeng Qinghong, the former vice president and de facto head of the Jiang faction. In addition, the article quotes Xi as saying that no official is “untouchable.”

Many observers have noted an apparent connection between the historical resolution and Xi’s effort to secure a third term as head of the CCP. Per current norms, Xi should step down in 2022, yet he has not designated a successor, and the propaganda issued at and around the Sixth Plenum seeks to justify his continued rule.

However, “the successful passage of Xi’s ‘historical resolution’ was a no-brainer; however, whether the Party elite are truly in ‘unison’ behind Xi” is another matter with the Jiang faction at large, according to SinoInsider.

“Xi is likely warning the Jiang faction and the ‘anti-Xi coalition’ against interfering with his effort to take a third term lest he is forced to ‘offend the people we must offend’ and purge ‘untouchable’ officials” such as Zeng and Jiang, the consultancy wrote in their Nov. 11 newsletter.

But whatever boost Xi derives from the propaganda offensive is bound to be temporary, as the PRC faces prolonged economic downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic, international condemnation and alienation for Xi’s authoritarian policies, and the risk of a collapsing real estate sector as Evergrande and other developers struggle to resolve their debts.

In the face of external crises and internal political struggles, Xi’s authority “is now more brittle than it was in previous years, and both he and the Party are becoming even more vulnerable to Black Swan events and other risks,” SinoInsider warned.