Seed saving is not merely an economical tactic that will save you a good bit of money in the future; it is also a responsible, sustainable, safe and easy way to make your world — and the world around you — a better place. There are many reasons to save seeds, and once you understand the basics, it becomes an obvious and entertaining way to make the most of your garden.

Garden genetics and seed saving

Understanding a little about how genetic information is passed on from plants to their seeds will help you weigh the benefits and risks in deciding what plants you want to save seeds from.

Pollination

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from the male to female parts of flowers for fertilization. It can only occur within a plant species, and results in the formation of seeds that carry the genetic information for a new plant.

When pollination is achieved in an uncontrolled manner (naturally via animals, insects, wind, rain etc.) the flower is open-pollinated. When humans purposefully transfer pollen for breeding purposes, it is cross-bred to produce a hybrid.

Hybridization

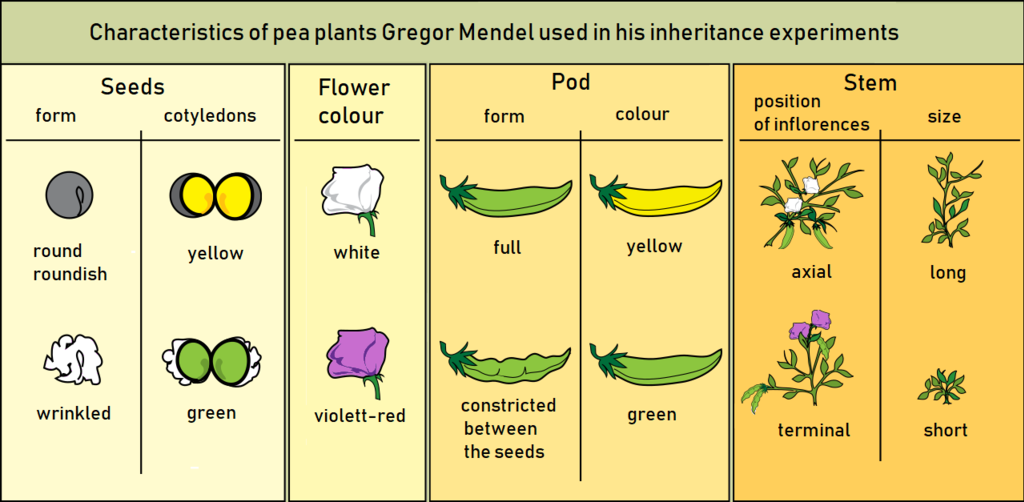

People have been selectively breeding plants ever since they were domesticated for agriculture some 10,000 years ago, but intentional hybridization began with monk Gregor Mendel’s genetic experiments in cross-pollination in the mid 1800’s. Hybrid seeds are bred to produce a plant with specific traits, passed on from its parents of different varieties within the same species.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Seeds from hybrid plants, however, will produce plants with a variety of traits from both parents, and only a fraction will resemble the hybrid. For this reason, it is not recommended to save seeds from hybrids. As long as the plant is not patented, however, you can feel free to experiment if you have the room and the inclination to explore new possibilities.

Cross-pollination

For seed saving purposes, open-pollinated plants are recommended because they have a common gene pool from like plants, and the seeds they produce will generally be true to type. As long as they are open-pollinated, plants that are self-pollinating — like legumes, lettuces, peppers and tomatoes — will produce offspring to match.

With plants that are pollinated by a vector, however, cross-pollination can occur naturally when different varieties of the same species are grown in close proximity (a home garden) during the same season. Thus, if you want to save seeds from species within the cabbage family, carrot family, squash family, or the beet family, you should only grow one variety at a time.

Reasons to save seeds

With an ongoing push towards disease-resistant, high-yielding, shippable, uniform hybrids — and even patented varieties — plant diversity is in danger. Treasured heirlooms are being taken off the market by big companies that supply the bulk of seed for commercial and home growers alike. By saving seeds from your own garden, you can resist this trend and ensure that your family will continue to have the home-grown produce you know and love.

Free seeds

Prices aren’t going down, and that includes the cost of seeds. Whether you have experienced dismay at the small number of seeds in a pricey pack, or had to pay an arm and a leg for shipping seeds that weren’t locally available, you can save yourself some money and frustration next year by simply collecting the seeds your plants naturally produce — and they all produce seeds, believe it or not!

Create and preserve tradition

Seed saving from the plants that do best in your garden is the original form of selective breeding. The plants will become increasingly well-suited to your particular conditions, and more likely to thrive.

Heirloom varieties are often more flavorful, more beautiful, and infinitely more interesting than the hyped-up hybrids that are flooding the market. Keeping a heritage line going is something that can be passed down through generations, and even become somewhat of a legacy.

Sustainability and self-sufficiency

Seeds are a renewable resource that you can collect. Depending on the plant, a single flower can produce two to two thousand seeds, and most plants produce many flowers. A single pea plant, for instance, might produce about 30 pods, each of which could contain five or more peas.

By saving the seeds from your favorite varieties, you can ensure that you always have the seeds to grow what you like, and be more self-sufficient. Share the surplus with your gardening friends and you will mutually expand your menu. Speaking of which, seeds like coriander (from cilantro), squash seeds, and mustard seeds are all good to eat!

Support biodiversity

Saving seeds from open-pollinated plants promotes biodiversity, not only for plants, but also for pollinators and other members of the animal kingdom. When you let plants go to flower, you feed a wide variety of beneficial insects — like pollinators and predatory wasps that will take care of many insect pests. Letting flowers go to seed is also a great way to attract birds and other critters to your garden.

Get to know your plants

By letting a plant mature and go to seed, you will gain a greater understanding of its life-cycle, and probably be a bit awed and inspired by the amazing things a plant can do. As your appreciative respect for nature grows, so grows your mind and spirit.

Four seed categories and how to save them

Flowers

While this article is focused on produce, ornamental flowering plants are a great place to start seed saving, since they are so simple. The seeds form directly on spent flowers; so, instead of deadheading everything, let some remain and mature. Collect the seeds from the plant soon after they are mature and dry. Leaving them after that runs the risk of insect, mildew or other damage.

Leafy plants

The countless leafy greens that come from the lettuce, spinach and cabbage families all require the plant to “bolt,” or go to flower. When you see the stems elongating on a head of endive or your kale is sending up shoots among the leaves, that is exactly what is happening.

Allow a couple of your healthiest and tastiest plants to flower. They will get tall and bushy, and might need staking to keep them upright. Enjoy the floral show and the flurry of activity as insects come to do their job. Wait for the seeds to fully mature, and then remove the whole plant. Place it in a covered, well-ventilated area to dry for about 10 days.

Kale, arugula, mustard greens and other cabbage-family members will produce tiny round seeds in long, thin pods. The plant can be pulled after the seeds turn brown. Crush the dried pods and then sift out the seeds with a sieve. The remaining pod bits can be winnowed away. Since cabbages are pollinated chiefly by insects, cross-pollination may occur if you grow more than one member of the family at a time.

Lettuce-family seeds (including endive, escarole, and radicchio) come with feathery hairs similar to their relative dandelion. Allow the plant to dry thoroughly before collecting the seeds. Rub the seed heads with your hands to separate them, then sift out the larger particles. Winnowing will remove the smaller particles.

Spinach is a little more tricky, since there are separate male and female plants. You will need both to get pollination, so allow a good handful of plants to go to flower. After you see seeds forming on some of the plants, you can remove the seedless males and give the females more space to mature. The seeds will form as little balls along a stalk, and are easy to rub off after completely dry.

Annual herbs like basil, dill, and cilantro will readily flower to finish their life cycle and produce plenty of seed, which can be harvested after it dries on the plant. Perennial herbs like thyme, rosemary, oregano and sage also produce flowers annually. Snip most of them to keep the plant producing leaves, but let some sprigs remain to produce seed. Parsley is a biennial that will flower and produce large umbels of seeds in its second season.

Fruiting plants

Seeds from fruiting plants will have a fleshy coating around them that you have to navigate. The fruit must be fully ripe — or even over-ripe — for the seeds to mature.

Peppers, for instance, won’t give you mature seeds if they are green. Pepper seeds are probably the easiest fruit-crop to save, but you must let your peppers realize their full beauty — be it red, orange or yellow — before collecting the seeds inside. Allow them to dry fully before storing.

Beans and peas that get too big for harvest are busy forming mature seeds. Leave them on the plant until dry, and then harvest and remove the shells. A handful of perfect pods will give you plenty for next season, but they will also store well in the freezer if you collect an abundance.

Winter squash seed is found within the hollow of the fruit with a bit of dry, stringy squash matter. Scoop the seeds out and clean them by letting them sit in a bowl of water for a day. The stringy stuff will soften, and the viable seeds will sink. Discard all but the good seeds, rinse them well, and let them dry for about 10 days.

Summer squash and cucumbers are the same deal, except you need to wait for the fruit to mature. They can grow to a tremendous size, and the outer skin will become tough and hard. Members of the cucurbits family will readily cross-pollinate, so only grow one variety per season if you aim to save seeds.

Non-hybrid tomatoes will yield true seeds, so you can grow as many as you like. Let the fruit get extra-ripe, and scoop out the gelatinous seed packs from the interior. Cleaning the seeds is a small fermentation project. Add about four times as much water as the volume of what you scoop out, cover with a napkin and let it sit for a few days. The natural bacteria in the air will work on breaking down the squishy stuff and freeing the seeds. Rinse repeatedly until only the sunken seeds remain. Allow them to dry on a screen or a cloth for about ten days.

Root vegetables

Root vegetables also flower and form seeds, although we rarely see them at that stage. Some can be collected in their first season, some the second, and some are more efficiently propagated by bypassing the seed stage.

Garlic and shallots, for instance, are best propagated by saving the cloves from particularly nice bulbs, while potatoes are saved to be cut into golf ball-sized chunks for planting. Sweet potatoes will send out small sprouts in the spring, which can be collected and rooted as slips for planting out in the summer. All produce that is propagated this way will be a clone of the parent.

Beets, carrots, onions and turnips are biennials that normally flower in their second year. Collecting from plants that flower in the first year would be selecting for inferior traits. Beets will cross with Swiss chard, so only grow one or the other each year. Both have clusters of seeds on a stalk that can be harvested similar to spinach seeds. Carrots will also cross-pollinate, notably with wild carrots, or Queen Ann’s lace, which makes them a challenge for seed savers in rural areas.

Salad radishes are a fast-growing root vegetable that will make seed in one season. It can be harvested like other cabbage-family members.

Seed storage

Once your seeds are clean and dry, you can store them in envelopes or small jars. Be sure to label each collection with the date, plant, and variety name. Keeping your collection in the freezer when you are not sowing can extend the life of your seeds. Some seeds — like cabbages and squash — can remain viable for many years, while others, like parsley and onions, will have poor germination after only two years.