While bird migration is widely studied and fairly well understood today, it wasn’t always so. In fact, the phenomenon was such an enigma that wild and magical theories were taken seriously and even accepted as truth.

It took nothing short of a miracle to uncover the mystery of migration.

No other bird flies as far as the North American Arctic tern. Tracking studies have found the birds make annual journeys of about 44,100 miles, nearly equal to a trip “around the world.” In its lifetime of up to 25 years, the Arctic tern could easily travel the distance between the Earth and the moon, times three (620,000 miles)! The journey some birds make in search of food and warmth is both monumental and heroic. For centuries it was shrouded in mystery, and speculation ran wild.

Myths

One theory, dating back to the ancient Greeks, held that certain birds’ seasonal disappearance was due to hibernation, much like their furry counterparts. Aristotle himself postulated that they morphed into other birds and back again. Many even believed that they flew to the moon and back. While we now know that many birds do have the endurance to fly great distances, even the Arctic tern would take several years to accomplish that feat, regardless of the daunting atmospheric challenges it would face.

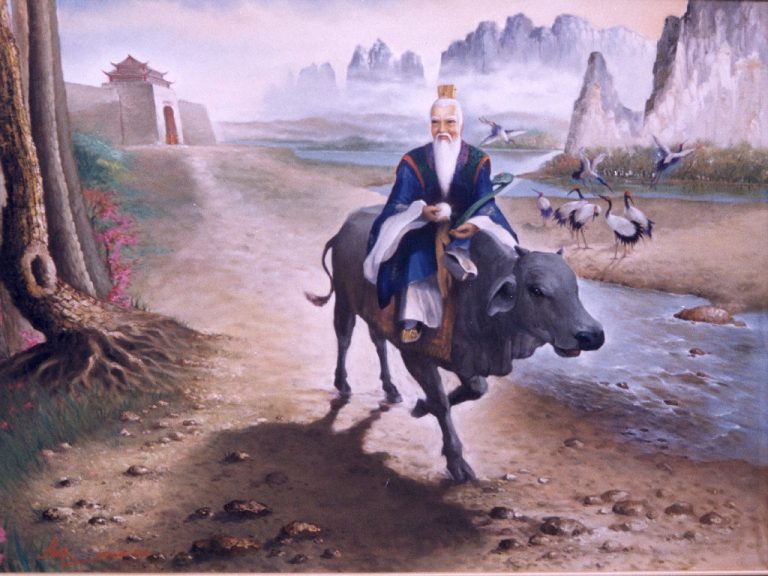

Perhaps the most fanciful explanation of the crane’s annual disappearance is due to an ongoing war with the Pygmies. In his epic tale The Iliad (eighth century BC), Homer references this myth in comparing the Trojan army with cranes:

shriek of cranes down from heaven

who flee the winter and the terrible rains

and fly off to the world’s end

bringing death and doom to the Pygmy-men

as they open fierce battle at dawn.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Roman author and natural philosopher Pliny the Elder (first century AD) reinforced this ancient lore with reports of pygmies eating the eggs and chicks of cranes to keep their population down, while fighting the birds on the backs of goats and rams, wielding arrows. As we will soon see, the arrow part is not entirely unfounded.

The white stork

White storks make their way back and forth from sub-Saharan Africa to their nesting grounds in Europe every year. Flocks of nearly 11,000 birds take an average of 49 days to cover the one-way distance of nearly 12,500 miles. The route from Europe takes them over the Strait of Gibraltar into the Sahara Desert, where heavy thermal systems assist in soaring, thereby conserving precious energy. After crossing the desert, they follow the Nile River south into their chosen country in Africa.

Back to Europe, they fly each spring, to hatch a four-egg clutch in a treetop nest made of sticks, sod, and mud, along with rags or other bits of human refuse. Where trees are lacking, a rooftop will do, as demonstrated in the charming children’s novel “Wheel on the School,” a Newbery Award-winning work by Meindert DeJong in which Dutch school children entice nesting storks back to their hometown through perseverance and cooperation.

In the Netherlands and other countries in Europe, storks are seen as good omens and are associated with springtime and fertility. They tend to return to their own elevated homes with the same partner. Their highly durable nests have often been known to last for centuries. These sturdy birds were the key to discovering what happened to many bird species at the change of seasons. Like a divine revelation, the answer came from above.

A white stork was spotted in 1822 near the village of Klütz, Germany; alive, but sporting a long spear through its neck. Upon investigation, it was discovered that the spear was made of African wood, indicating that the bird had made its way to Africa where it was apparently shot and injured. It subsequently managed to fly back to Germany, where it was discovered, killed, and stuffed. Over time, an additional 24 such birds were spotted, enough to earn them the German name of Pfeilstorch, or Arrow-stork.

Why migrate?

Puzzling as it may be to ponder why a bird would go through the time and trouble to fly so far every year, and why some birds do and others do not migrate, according to the Washington Post, 2018 studies suggested that it all boils down to energy efficiency.

In other words, “the energy cost to a bird of flying long distances is balanced out by the energy savings of being in a place where, in summer, there are lots of mosquitoes, flies, insect larvae and other avian delicacies, and there is relatively little competition for food.”

Yet according to Peter Marra of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, “migration is a very flexible trait.” This instinct can be overwhelmed by changes in the environment. Here in New Jersey, the Canadian geese have become permanent residents of our parks. Our friend the white stork, too, is often enticed by the free eats found at landfills in Spain and Portugal, thus foregoing its annual travels.