While every day is arguably unique, leap day is four times more so, simply for its scarcity! As with many things, February 29 is favored by some and feared by others. Since its inauguration nearly 2,000 years ago, Leap Day has accumulated its fair share of folklore and quirky customs, but should not be confused with Sadie Hawkins Day, which falls in November.

Where did leap day come from?

The Gregorian calendar that we use today has its roots in early Rome, which, like many ancient civilizations, took both the lunar and solar cycles — or seasons — into account. The discrepancy in days between the lunar and solar cycles, however, proved to be a universal conundrum. Some cultures introduced whole “leap months” to address the problem, while others distributed the days somewhat evenly between the lunar months.

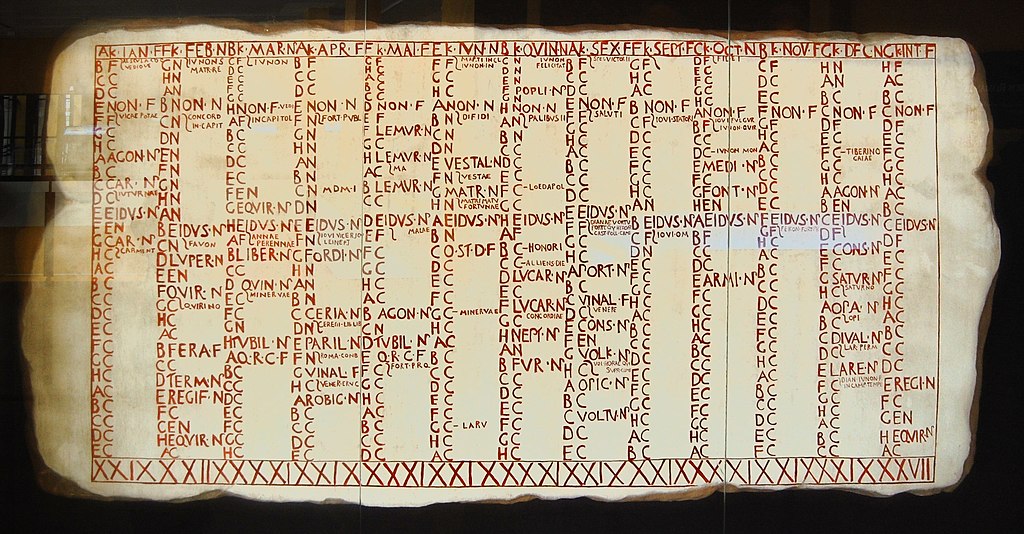

The early Roman calendar, said to be invented around 753 BC by Romulus, the first king of Rome, consisted of 10 defined months (March – December) followed by a flexible, “winter period” to be endured before serious agriculture endeavors began again.

Rome’s second king, Numa Pompilius, reformed the calendar around 713 BC by assigning these nebulous winter days to two new months (January and February) at the end of the religious year; although they soon became recognized as the beginning of the civil year. Numa gave each of the 12 months an odd number of days — for good luck — but there were still extra days, called intercalations, to deal with.

In time, these intercalations fell into political misuse, and Rome became rife with both corruption and confusion regarding dates. Fortunately, Julius Caesar discovered a remedy in Egypt’s fixed 365-day calendar during his stay there between 48-46 BC.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

When he returned to Rome and took office, Julius and his council of philosophers and mathematicians adapted the Roman calendar to Egypt’s fixed year length, which, according to Greek astronomy, was 365¼ days. When it was adopted in 45 BC, the Julian calendar looked very much like our present-day Gregorian calendar, complete with a Leap Day every fourth year in February.

Many centuries later, however, it was observed that we were again falling out of sync with the cosmos. A more precise solar cycle of 365.2422 days was found to not warrant all the leap days that had been allotted, and the calendar was revised once again in the 16th century.

Our current Gregorian calendar is named after Pope Gregory XIII, who initiated changes to keep Easter from drifting out of spring. The ten days that had accumulated were cut out of October 1582, and the Leap Day schedule was amended to exclude century years, unless divisible by 400. Thus, 1900 was not a leap year, 2000 was, and 2100 will not be.

Leap Day Love

Leap day has long been recognized as a suitable day for a woman to propose marriage to a man. According to legend, St. Brigid of Ireland lamented to St. Peter about women never having the chance to make this important move in a relationship, and the wait for a shy guy might be ages. This special opportunity was granted, and officially recognized as Ladies’ Privilege, observed on Leap days.

Since then, many unusual customs have arisen in conjunction with Leap Day proposals.

In Ireland, refusing a woman’s proposal entailed some compensation — such as a gift of expensive clothing or fine gloves — for her disappointment.

Ladies’ Privilege was adopted into law in Scotland by Queen Margaret in 1288. Here it was required for women to wear a red petticoat if they were making a proposal, perhaps to give their intended fair warning.

In Denmark, the penance for refusing a woman’s proposal on Leap Day was 12 pairs of gloves, presumably to hide her ringless finger.

In Germany, Leap Day is the chance to reverse another tradition: It is common for boys to place a decorated birch sapling in front of the home of the girl they like on May 1. On Feb. 29, girls take that initiative.

Unlucky Leap Day

While some European women are placing their highest hopes on Feb 29, others find it dreadfully unlucky.

In Greece it is widely believed that marriage in a leap year will end in divorce. Even leap year divorces are said to bring perpetual sadness.

In Taiwan, the elderly are in danger of misfortune during leap years. Their married daughters will often return home to look after them and cook them lucky pigs’ feet.

In Scotland, a leap year is considered a bad year for sheep, and any person born on Leap Day is likely to have a miserable life.

Leaplings

About 5 million people have Feb. 29 birthdays. Considering the fact that motivational speaker Tony Robbins is one of them, the Scottish superstition may not be absolutely correct. Having this most unusual birth date entitles Leap Day babies to the distinctive moniker of “leapling.”

The fictional hero Superman was a leapling, but most leaplings lack superhuman powers. They age just as fast as the rest of us, and often encounter frustrations with paperwork due to their irregular birth date. Most years, leaplings have to choose whether to celebrate their birthday on Feb. 28 or March 1, but this year they have a day of their own.

Happy birthday Leaplings!