In the 7th century A.D., China’s Sui Dynasty collapsed. Wasteful policies and civil war devastated the country and its people.

Moving out from their northern stronghold of Taiyuan, aristocrat Li Yuan and his sons raised an army and defeated the warlords vying for control of the broken empire, bringing order to China under the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

On the battlefield, Li Yuan’s second son, Li Shimin, demonstrated both tactical excellence and strategic vision. When the war was won, Li Yuan, now emperor, wanted to forgo the tradition of naming his firstborn son crown prince, and give the throne to Li Shimin instead.

A righteous coup

But it had been mere decades since Yang Jian, the emperor of the Sui Dynasty, had turned the throne over to his treacherous and arrogant son Yang Guang, who, like Li Shimin, was also a second-born. Yang Guang’s mad desire for luxury and extravagance doomed the Sui to a mere 40 years of existence.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Even Li Shimin himself disapproved of his father’s idea.

But it turned out that history does not always repeat itself. Immediately following the victory of the Tang, Li Shimin’s older and younger brothers began plotting to usurp their father. With the power to command their own private armies, they began affairs with Li Yuan’s imperial consorts and hunted commoners for sport.

Only Li Shimin remained loyal, staying away from politics and only mobilizing his forces when the Tang came under attack by the Turkic tribes of the north.

His brothers knew that that the one force stopping them from overthrowing Li Yuan and dividing China between themselves was Li Shimin.

Hearing of his brothers’ conspiracy to assassinate him and seize power, Li Shimin considered letting himself be killed to ensure a smooth imperial succession. At this juncture, one of his subordinates protested vehemently: The other princes were debauched scoundrels certain to destroy the Tang if allowed to prevail in their designs. For the sake of their father’s legacy, Li Shimin could not afford to die.

Before the impending coup, Li Shimin and his supporters planned their own moves. Leading elite troops to the Tang capital of Chang’an, Li ambushed and slew his wicked brothers outside the northern gate of the imperial palace. Sixty days later, Li Yuan abdicated, and Li Shimin became Emperor Taizong.

Ruling with magnanimity

Emperor Taizong was perhaps the greatest of all rulers in Chinese history. His 23 years of enlightened rule, the Reign of Zhenguan (貞觀之治), saw the rise of a prosperous and cosmopolitan empire that received emissaries and scholars from dozens of kingdoms throughout Asia.

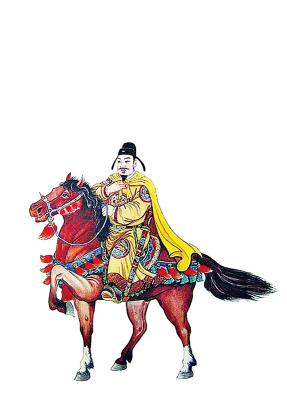

Emperor Taizong was perhaps the greatest of all rulers in Chinese history. (Image: Public Domain)

Taizong never forgot the bloodshed that brought him to power. He made sure to respect the opinions of his ministers, and even encouraged them to raise objections to him while holding court.

In the early Tang Dynasty, the population was starving and there was much rebuilding that needed to be done. The weak rule of Li Yuan and the corruption of Taizong’s late brothers had not helped to improve the state of the empire, and Turks continued to threaten its northern frontier.

Instead of piling taxes on the people, Emperor Taizong dropped fees and ran government on a smaller budget. He did everything to prioritize industriousness among the Tang subjects. The legal code was simplified for commoners, but officials were held to high standards of conduct.

Once, when Emperor Taizong was holding a discussion with his ministers, one official recommended using stronger laws to deter thieves.

Taizong said: “People steal because the government taxes them heavily and they have to do a lot of work for the government… If the people live in poverty, they will steal shamelessly. We should stop unnecessary spending, save costs and reduce expenses, and promote honest officials. That way, people will have enough food and clothing, and they will not need to steal. What need do we have for harsh laws?”

Like all successful Chinese rulers, Emperor Taizong placed great emphasis on moral teachings. He made efforts to ensure that China’s native religion, Taoism, could coexist in peace with Buddhism, which was introduced from India and was becoming increasingly important in Chinese spiritual life. At the same time, his rule embodied China’s secular Confucian morality.

The Tang Dynasty was one of the peaks of Chinese civilization. ((Image: Public Domain)

Order through virtue

Despite the hard times, society was in good order, as people learned to improve their personal conduct and behave as proper subjects. It was said that even as wealth increased, people would leave their doors unlocked at night and did not hesitate to offer food to travellers.

Even criminals seemed to be reformed by Taizong’s reign. A famous story tells of how one year, 70 death-row convicts were to be executed for serious offenses. But Taizong ordered that the criminals be given one year of freedom so that they could return home to spend the New Year with their families.

Amazingly, when the one year was over, every one of the convicts reported to the authorities to receive their punishment. Seeing the trust that his people had in him, Taizong gave them a collective pardon.

One reason why Taizong was remembered as such a great emperor was because of the trust he had cultivated in his subjects.

On one occasion, Taizong was discussing the characteristics of good government with two of his ministers. “How do I compare with Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty?” He was referring to Yang Jian, who was a shrewd and extremely hardworking emperor.

They said: “Although he did not have compassion, he was a diligent emperor.”

Emperor Taizong replied: “You see only one aspect of the situation. Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty made decisions on everything personally instead of relying on his officials.

“The world is so big and there are so many things to deal with. A person could work himself to death, but still not deal with everything well by himself! His officials knew how he ruled his empire, and they all waited for his decision. They kept their own thoughts to themselves and did not dare to speak up. That was why the Sui Dynasty only lasted for two generations.

Follow us on Twitter or subscribe to our weekly email