It has now been 257 days since the military declared a “one-year-long state of emergency,” seizing power in Burma, also known as Myanmar. Burma’s UN envoy says the nation is now threatened with a “failed state” status. Meanwhile, Aung San Suu Kyi’s UN ambassador has been vying to keep his UN General Assembly seat despite a February diplomatic ousting by the junta.

The junta has been pressuring the UN to install an ambassador who will represent the military dictatorship, meanwhile, the ambassador affiliated with the ousted party has not left his post. This is occurring while a second multi-national coalition, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), has denied recognition of Gen. Min Aung Hlaing’s military rule.

The United Nations’ nine-member credentials committee will vote this November to see if the military junta can gain UN Representation, taking over the UN assembly seat that had been given to Aung San Suu Kyi’s government under the National League of Democracy (NLD) party. The seat is still held in the UN by the “fired” ambassador, Kyaw Moe Tun, who has been accused of high treason by the military government of Burma. Kyaw Moe Tun has called for sanctions and international cooperation against the junta while remaining a member of the General Assembly.

358 civil organizations located in both Burma as well as globally, sided with the career diplomat in an open letter in early September. The letter described him as having “provided a crucial voice at the UN for Myanmar’s democratically-elected government and people.” Others consider him a mouthpiece. Either way, he refuses to leave his post at the UN, and the UN continues to recognize him, declining to call a meeting despite pleas from the military leaders of Burma throughout the lifecycle of the coup and ensuing military government.

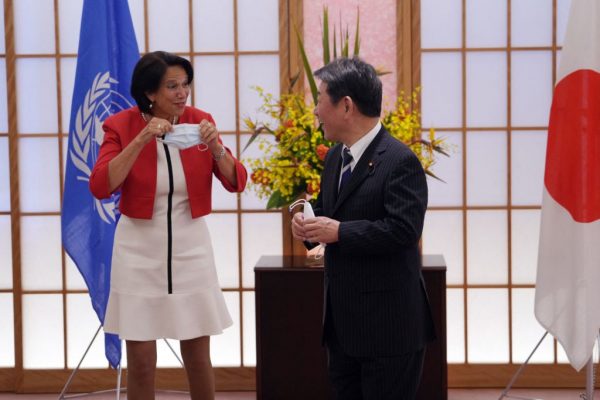

Speaking of the present situation as the upcoming vote draws near, the UN Secretary General’s Special Envoy to Myanmar, Christine Schraner Burgener, said that it was very important not to send any signals recognizing an illegitimate regime and that “we want to respect the will of the people.” She is referring to what she believes is the veracity of an 82% vote for Suu Kyi’s party at the last election. The military junta, led by Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, proposed that election fraud had occurred and began a coup after appeals were denied.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The international community — with the exception of Russia and only a few closer partners in the Asia Pacific who remained on the fence, such as China — has largely refused to recognize the junta. Economic sanctions and brand withdrawals have also taken place, as the international business has sought to align with the overall international tone. China had been especially interested in the Southeast Asian nation, with aims of developing a deepwater port on the Bay of Bengal, from which a railroad or high-speed train could be developed, connecting China with the Indian Ocean. This was a key element in China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as foreseen within Burma, and Aung San Suu Kyi‘s government had signed contracts to that end.

At the United Nations, the 193-member General Assembly is tasked with accrediting diplomats. The nine-member credentials committee is the first stop on the path towards accreditation in the larger assembly. The credentials committee this year comprises Cameroon, China, Iceland, Papua New Guinea, Russia, Trinidad and Tobago, Tanzania, United States, and Uruguay.

The credential committee does typically meet in October or November, so the November convocation is a usual occurrence and not a capitulation by the committee to entertain the months-long pleas of the junta for a hearing. The committee did not call a special assembly as requested by the military junta in July. As for the Suu Kyi government’s UN ambassador, according to the Malaysian news source, The Star, “until a decision is made by the credentials committee, it has been decided that Kyaw can remain in the seats, as long as he doesn’t speak at the General Assembly rules.”

Schraner Burgener warned that “the overall situation in Myanmar continues to deteriorate sharply,” and that if the democratic government of Suu Kyi was not restored, returning the power “to the people”, then Burma “will go in the direction of a failed state.”

Schraner Burgener said, “The army uses a range of tactics against civilian populations, including burning villages, looting properties, mass arrests, torture and execution of prisoners, gender-based violence and random artillery fire into residential areas.”

Schraner Burgener said the health and banking systems had collapsed and the number of people requiring humanitarian assistance has increased by 2 million since the coup.

According to a USDA report from April 2021, which cites the unrest as hampering trade, “the February 1, 2021 coup d’état and country-wide largely peaceful protests in opposition to the military’s actions, and the military’s increasingly lethal response, have continued to hamper the logistics sector. “ However, at this juncture “largely peaceful protests” are no longer the norm.

According to The Star of Malaysia, Burma is now seeing a “‘full-scale revolt’ by the ‘People’s Defense Forces’ or local militias endorsed by the elected National Unity Government” and that the revolt “is claimed to be the last resort in the face of continued attacks and alleged massacres by the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military).” The Star quoted activist Khin Omar as saying that this last bastion of resistance is occurring “even in places where people have never seen armed conflict” apart from airstrikes in areas run by ethnic resistance armies.

Schraner Burgener of the UN is now comparing the military junta’s present occupation to actions the military carried out against the Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, beginning in 1997. In the past, invocation of “Rohingya” meant, to some, using a watchword for bringing UN intervention into the country of Burma, although the reality on the ground is complicated and the group has indeed experienced great suffering. It may be that Schraner Burgener’s comparison as well as her use of the word “failed state” have invoked the rhetoric, if not the eventuality, of UN actions regarding Burma.

The upcoming ASEAN gathering, composed of 10 Indopacific nations, has not invited military junta leader General Hlaing to the table. According to Schraner Burgener, this has sent “a clear signal that they also agreed together that the current situation is unacceptable.”

Gen. Hlaing, for his part, accuses ASEAN nations of failing to suppress opposition violence in groups that are against his rule. According to one Malaysian news source, while the Indopacific does observe that the military leaders of Burma “retain a fairly respectful place” on the world stage, whether they should or not is a matter of heated opinion; and an overwhelming representation of news sources online has painted the junta as a detested military dictatorship. Hlaing, in a speech broadcast on Burmese state television, said that groups, which had been organized to oppose the military takeover, had been responsible for the ongoing and deadly unrest. He suggested that ASEAN had failed to admit that these opposition groups had caused the violence and said his government was seeking to restore stability and peace. For those who observed the coup unfolding in the early days, there was indeed a lull during which curfews and rules were adhered to before resistance began to coalesce. One student interviewed at the time at a university where protests were in their nascent stages proudly named her student leader who was organizing the protest. Violent protests were photographed occurring in other Asia Pacific countries much sooner than they occurred within Myanmar.

At this point, the violence in Burma has escalated. Schraner Burgener says that “civil war” is not “international legal terminology,” so she won’t use it, but that the widespread, polarized unrest is now “an internal armed conflict.”

Schraner Burgener commented on the violence from the protestors, stating, “Clearly, in the absence of international action, violence has been justified as the last resort.” By contrast, Gen. Hlaing has said, in not so few words, that the violence within his country has international support.