First published in 2006 by the Chinese-language Epoch Times, this series lays out in detail the vast system of Communist Party culture that dominates mainland China today and how it violently replaced the ancient moral and spiritual heritage of the Chinese people. Vision Times is proud to present a translation of Disintegrating the Culture of the Chinese Communist Party that sheds light on the fundamental characteristics of the world’s biggest communist state, while keeping true to the message intended by the original authors.

Chapter Two: The Establishment of Communist Party Culture (Part II)

Continued from Chapter Two (Part I).

Denouncing Confucianism

The Chinese have always taken family to be the core of social life. Confucian teachings, which articulate the principles of family morality, as well as public life and governance, have guided social values in China and much of East Asia for over 2,000 years.

Among the Three Religions, Confucianism focused almost exclusively on the secular sphere, and had the greatest influence on everyday life. Confucius lived in the turbulent era of the late Zhou Dynasty (770–256 B.C.), sparing no efforts to promote the rites and morality of the ancients. He was also an advocate of learning, instructing thousands of students from all social strata.

Duke Ai of Lu State erected a temple to pay respect to Confucius; Emperor Gaozu of the Han empire developed court etiquette according to the great teacher’s protocols.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The greatest rulers of Chinese history paid their respects to Confucius. Gaozu’s descendant Emperor Wu, who made Han China into a superpower, honored Confucianism alone among the “Hundred Schools of Thought” and enshrined it as the state ideology. Tang Dynasty Emperor Taizong honored Confucian classics and bestowed a regal title upon the sage. Emperor Kangxi, who ruled the Qing Dynasty for 60 years, hand-wrote the exaltation “model teacher for all time” and had the calligraphy placed at the Confucian ancestral temple.

Nearly every dynasty honored Confucius, and his influence extended far beyond state boundaries. Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and other Asian countries inherited many ideas from Confucianism. During the Enlightenment, great philosophers such as Leibniz and Voltaire found inspiration in Confucian classics.

Starting with the Han, all dynasties in ancient China paid respects to Confucius. Slandering the “eternal teacher” and smashing Confucian temples were things only the Communist Party dared do.

Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China, suppressed all schools of thought, including Confucianism, in favor of the strict Legalist ideology. Despite unifying the country and pioneering the system of imperial rule, the First Emperor’s realm fell apart just three years after his death.

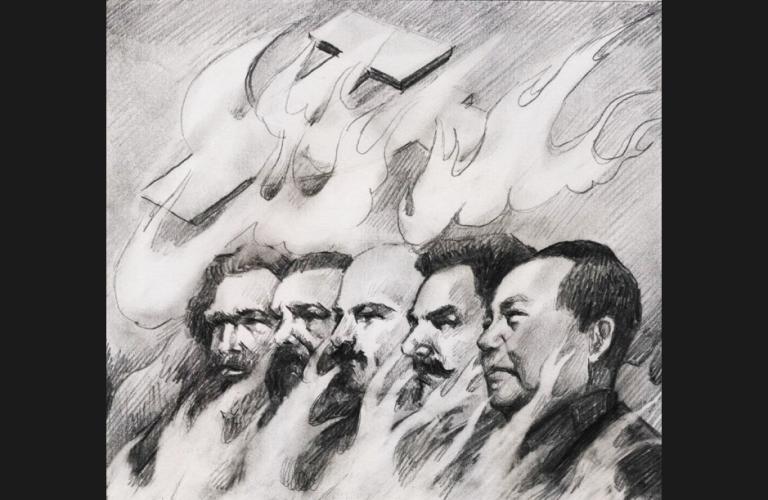

Mao Zedong hated China’s Confucian culture and admired the Legalist ideology for its emphasis on political intrigue, manipulation, and total obedience from the masses — qualities that fit well with communism. Mao sought to outperform Qin. While the Qin Dynasty forbade casual learning and discussion of non-Legalist philosophies, the imperial government kept copies of the major classics in a grand library for special research. Under the Chinese Communist Party, the entire society was mobilized to denounce Confucianism and the rest of traditional Chinese culture as part of the hated “Four Olds.”

Confucius, who advocated “civility, generosity, loyalty, and integrity,” was lambasted by the CCP as “the personification of all old theories; the soul of all that is wicked.” The Party claimed:

“Confucius is the arch-criminal of all ages since the birth of our people; his evil reaches the extreme; he is the public enemy of good folk, the majority of the people. Starting today, humanity shall arise as one to besiege him, let it be done! Of all the thinkers from ancient times to today, the words and deeds of Kong Qiu [Confucius’ given name] are the most absurd, bar none.”

During mass political movements, these crude denigrations filled the state media everywhere. However, of the articles criticizing Confucius, taking statements found in Confucian classics out of context, or devolving into various kinds of sophistry, none are convincing, and serve merely as vehicles of the class warfare found in Communist Party culture.

Taking class struggle as the starting point, the CCP criticized Confucius as “representing the interests of the slaveowning class.”

The irony of this is apparent. Soon after taking power, the CCP executed millions and sent millions more to forced labor camps. Under the campaigns of the 1950s, farmers who had been supposedly liberated became little more than serfs managed by communist committees. Before communism, even in the chaotic era of civil war and foreign invasion many peasants were able to gain some wealth by working their land, but in the CCP’s “land reform” movement many of them were branded “rich farmers” and expropriated or shot.

In more recent decades, the CCP allowed capitalists to join its ranks; deep collusion between politics and business has created runaway corruption that — even in the words of today’s Chinese leaders — threatens the future of the country. For a party that came to power by robbing and murdering “landlords” and “rich farmers,” the CCP’s theories of liberation and socialism are now utterly bankrupt, except as a means of maintaining its totalitarian power and crushing dissident.

Accordingly, the Party’s fanatical attacks on Confucianism have been replaced by the CCP’s attempts to legitimize its rule through superficial promotion of Confucius. The Party has spent billions on its overseas “Confucius Institutes,” which are widely criticized as propaganda vehicles for spreading communist interpretations of Chinese identity and good feelings for the CCP.

In fact, the CCP’s antagonistic stance on Confucius and traditional Chinese culture have never fundamentally changed. While the authorities no longer slander Confucius and traditional culture, it is still important to expose the fallacious methods the CCP used to attack him, since the Party recycles the same technique to attack all kinds of people or ideas it deems to be the enemy.

In the book A Comprehensive Critique of Traditional Chinese Thought, written following the communist takeover in 1949, author Cai Shangsi attempts a total refutation of Confucius. Eight major fallacies can be identified in these criticisms.

1. Taking Confucius’ deeds out of context: Cai claimed that because Confucius charged tuition, he was a servant of the wealthy and a hypocrite. In fact, Confucius believed in equal opportunity to learn for people of all social classes, not necessarily that education should be provided to everyone free of charge. One of his most famous disciples, Zi Lu, was born into a family of poor commoners.

2. Attributing other people’s words to Confucius: The Biography of Guliang in the Spring and Autumn Period, an important historical document, was written by a student of Zixia, but Cai Shangsi used a discussion of the villainous figure Boji in the book to criticize Confucius.

3. False equivalency: The Critique took aim at Confucius’ words “when not in a position of leadership, do not try to lead,” claiming that this statement is the same as encouraging people not to serve the country or care for society. In fact, Cai purposely confuses Confucius’s statements about rank with his teachings on civic or moral duty.

4. Illogical comparisons: The Critique claimed that because, like Legalism in the Qin Dynasty, Confucianism was honored as the state ideology during the Han, Confucianism was merely a tool of imperial tyranny. Cai’s comparison wholly ignores the differences between the Confucian and Legalist philosophies — the former emphasizes virtue and moral behavior, while the latter is concerned with political maneuvering and the implementation of strict laws to strengthen the state.

5. Assuming that one proposition automatically implies the reverse: For example, while critiquing Confucius’ supposed attitude on women, Cai writes that “if women are regarded as inferior, clearly all men must be superior individuals.” (Contrary to Cai’s claim, Confucius never taught that women should be “regarded as inferior.”)

6: Using “science” as a philosophical critique: Cai claimed that Confucianism was a “violation of natural science,” but Confucius taught almost exclusively about the ethical and social dimensions of life. Science may be used to determine material laws, but not questions of philosophical or moral gravity, such as the definition of good and evil. Moreover, of the “Six Arts” Confucius advocated, one was math — the foundation of natural science.

7. False accusations: Cai cites examples of ancient Chinese women who tragically committed suicide after the death of their husbands as evidence of misogyny in Confucius’ teaching. But in reality, Confucian classics do not describe requirements for widows, and Confucius’ own daughter-in-law and grand-daughter-in-law were remarried.

8. Red herrings: Confucius once said, “do not eat putrid fish or spoiled meat.” Though such advice is common sense, in the Critique, Cai Shangsi once again skewed the meaning of this line, claiming that it demonstrated the teacher’s life of luxury and excess.

While Cai’s book may be long-forgotten, the arguments he uses are recycled time and again by so-called “experts” the CCP tasks with guiding public opinion and indoctrinating students to hate whomever happens to be the Party’s current target.

To be continued.