Indigenous peoples have inhabited Earth for millennia. Being descendants of the first occupants of a given region, each native population has its own way of life and worldviews that are passed down through countless generations in the form of culture and traditions.

Although each aboriginal group is extremely unique, cultural studies have found that they share surprisingly similar features when it comes to their interaction within their communities and their connection to nature.

While their lives unfold in a radically different setting from ours, the essence of many of their traditions are rooted in a deep understanding of life and its connection with the Universe. Hence, the values they preserve can remind us of our inherent human nature and the noble aspirations any person can have, even within our modern environment and lifestyle.

Forgo the material to gain true wealth

Living far from urban settlements, hunting and farming are the main activities of many indigenous groups. A 2017 study by the Environmental Science and Technology Institute of the Autonomous University of Barcelona revealed that social interactions, successful hunting and good health, make indigenous people happier than money does.

The study analyzed the lifestyle of the Punani Tubu tribe in Indonesia, the Baka in Cameroon and Congo, and the Tsimane in Bolivia. It found that its members spend a maximum average of thirty hours per week working – hunting, gathering or farming – and have enough free time to nurture social relations and do other activities that contribute to their emotional wellbeing.

Another study made in 2006 indicated that a group of people from the Maasai tribe in Kenya and Tanzania, had a Satisfaction with Life Index similar to that of the four hundred richest Americans on the Forbes list. The study concluded that economic development and material wealth are not a condition of happiness, suggesting that a simple and balanced life can lead to fulfillment.

Nature does not belong to us, we belong to Nature

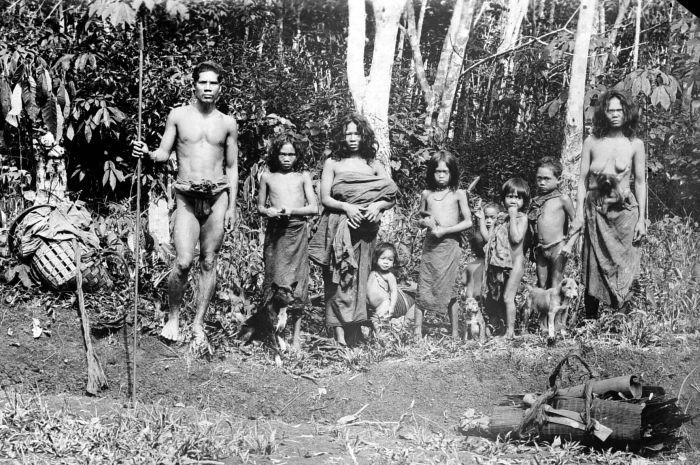

Tradition has it that when a member of the Orang Rimba tribe is born, their umbilical cord is buried in the rich forest soil on top of which a tree is planted. The tree and the individual grow concurrently, creating a lifelong spiritual bond. The individual must protect his “birth tree” from any attack or logging attempt, and any damage done to the tree would equate to harming the person.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

For most tribes, Nature is not only their home but also their source of food, medicine and spirituality. Their close contact with the wilderness has led indigenous peoples to study the environment, understand its cycles, and adapt their way of life to live in harmony with it.

For instance, when the Yanomami people settle down in an area, their activities often result in the reduction of mammal populations and the exhaustion of palm trees whose leaves are used for roofing their homes. But as damaging as it sounds, this tribe knows natures’ limits, and before any permanent harm is done, they move to another area, only returning after the forest is fully recovered.

Indigenous people take only what they need to survive. They do so with great consideration, based on a profound knowledge of what nature can provide and to what extent. This understanding of nature is passed down from generation to generation and is learnt from the earliest years.

The Yanomami children, for example, are taught how to “read” animal tracks and use plant sap as poison for hunting. Likewise, the Moken youngsters learn to observe nature by developing a unique ability to focus their eyesight underwater to find food on the seabed. Similarly, Omo tribes in Ethiopia carefully study the river’s flood cycles so that when the waters recede, they can use the rich silt deposited on the banks to grow their crops.

In his book The Falling sky, Davi Kopenawa, a Yanomami shaman, describes how comprehensive native people’s knowledge of nature is and how it can contribute to the protection of the environment today. He explains that millions of indigenous tribes have studied the ecosystem for generations and that they know how to protect nature, as it is an essential component of their culture and spirituality.

The respect for the environment has been fundamental to many ancient civilizations and aboriginal groups. Because people in the past honored the natural equilibrium of things and coexisted in harmony with nature, it was possible for humankind to survive as a species. However, in a short span of decades, the environment has suffered exponential damage never seen before, making traditional knowledge more essential than ever.

Always put others first

The aforementioned Yanomamis have a very peculiar habit. When they go hunting, they never eat what they hunt nor do they take it home. They usually bring it to the village where the food is shared with others. Hunters only eat food that is provided by someone else.

Early on, Yanomami girls learn how to help their mothers grow crops, carry water from the river and cook for the community. In the tribe, all Yanomami children are taught that sharing is a fundamental pillar of the group, and every member can participate in community decision-making.

For the Hadza people of Tanzania, it is an instinct to share their belongings if they are not being immediately used, and it is part of their character improvement to expect nothing in return. In the San tribe in Botswana, young ones are advised to be courageous but humble, emphasizing generosity as an admirable quality and selfishness as an undesirable trait.

Still more remarkable, the selflessness of many tribes goes beyond their communities. When the Baka Pygmies of Central Africa gather sweet potatoes, they make sure the root is left intact. This favors the spread of their growth in the forest, where elephants and wild boars also feed on these delicacies.

Compared with the dynamic environments in which most of us live, the lifestyle of indigenous peoples may be summed up in one word: “simplicity.” Nevertheless, it reveals a precious wealth of information they have in their minds and hearts. The way they gather food is a telling case.

When collecting food, a tribe member is not thinking of satisfying his hunger; instead, he is motivated by the responsibility of feeding his community. Every bit of additional effort he puts in is likely to be rewarded by smiles at the moment of eating together.

Mother Nature is also on his mind during the activity. Based on his extensive knowledge of the cycles of the forest, he will not take more than the ecosystem can provide, and no permanent damage will be made to their food source, which also happens to be their temple and home. And as if this consideration was not far-reaching enough, he will make sure that the animals, who share the land with them, also have a source of food to satisfy their hunger.

Selflessness, living in harmony with nature, and finding satisfaction in simple living are some of the numerous lessons aboriginal peoples can teach us. Considering that the traditions they uphold originated from earlier times during which everyone lived in harmony with the Universe, we could say that by learning from ancient traditions we may approach our true selves.