The United States and China have maintained a significant scientific and technical cooperation agreement for over 40 years, showcasing the potential for the two rivals to collaborate despite their disputes. However, as bilateral relations reach their lowest point in decades, there is an ongoing debate within the U.S. government regarding the expiration of the U.S.-China Science and Technology Agreement (STA) later this year, according to three officials familiar with the discussions.

As Secretary of State Antony Blinken visits Beijing, marking the first visit by a secretary of state in five years, expectations for any breakthrough in bilateral relations are low. The debate surrounding the oldest U.S.-China bilateral cooperation accord reflects a broader question among policymakers: Does the benefit of engaging with China outweigh the risk of empowering a competitor that operates under different rules?

The STA, initially signed in 1979 when diplomatic ties between Beijing and Washington were established, has been hailed as a stabilizing force for the relationship between the two countries. It has facilitated collaboration in various fields, including atmospheric and agricultural science, as well as fundamental research in physics and chemistry. Moreover, it has laid the groundwork for a flourishing of academic and commercial exchanges.

While these exchanges have contributed to China’s rise as a technology and military powerhouse, concerns have emerged regarding Beijing’s theft of U.S. scientific and commercial achievements. This has led to questions about whether the agreement, set to expire on August 27, should be continued.

Supporters of renewing the STA argue that terminating it would stifle academic and commercial cooperation. However, a growing number of officials and lawmakers, speaking anonymously due to the sensitivity of the issue, believe that cooperating with China on science and technology makes less sense in light of the countries’ competition.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Representative Mike Gallagher, the Republican chair of a congressional select committee on China, expressed his perspective: “Extending the Science and Technology Agreement between the U.S. and China would only further jeopardize our research and intellectual property. The administration must let this outdated agreement expire.”

The U.S. State Department declined to comment on internal deliberations, while the National Security Council also refrained from providing a statement.

READ MORE:

- Antony Blinken Meets With Xi jinping Amidst High Sino-US Tensions

- South Korean President Hits Back at ‘Wolf Warrior’ Rhetoric From China’s Ambassador Xing Haiming

- China’s Imports and Exports Shrink as Domestic Demand Falls, According to May Data

China’s embassy in Washington mentioned that Chinese officials approached the U.S. a year ago to discuss the agreement, which has formed the basis for four decades of fruitful cooperation. They expressed hope that the U.S. would expedite its internal review before the agreement expires, suggesting that both sides could consider adjustments to the original deal.

“As far as we know, the U.S. side is still conducting an internal review on the renewal of the agreement,” embassy spokesperson Liu Pengyu said according to Reuters, adding that both sides could consider adjustments to the original deal.

Within the U.S. government, including the State Department, which leads the negotiations, there are differing opinions regarding whether to renew, let expire, or renegotiate the pact. Some officials believe that attempting to renegotiate could potentially derail the agreement, given the current state of U.S.-China relations.

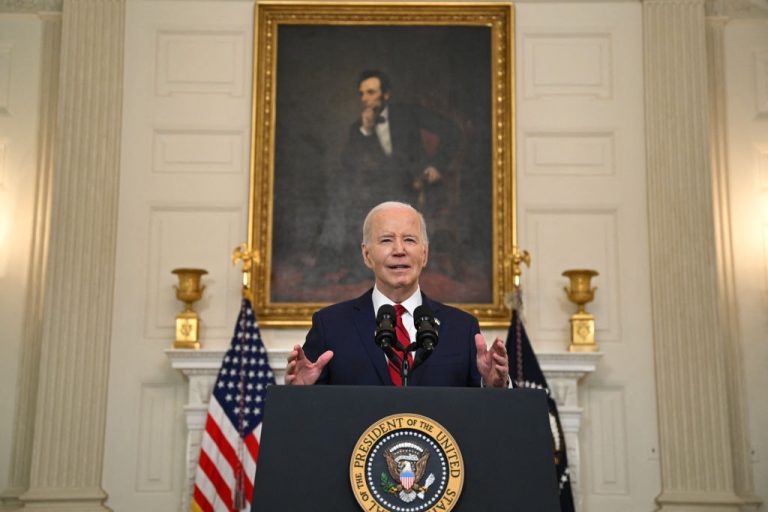

U.S. businesses have long complained about Chinese government policies that require technology transfer, and concerns persist regarding state-sponsored theft of valuable information. The Biden administration has emphasized the importance of technological competition, acknowledging that technology will be the key arena for global competition in the future.

“Technology will be the cutting-edge arena of global competition in the period ahead in the way nuclear missiles were the defining feature of the Cold War,” U.S. Indo-Pacific coordinator Kurt Campbell told a Hudson Institute forum in June, adding that the U.S. “will not cede the high ground.”

Proponents of renewing the agreement argue that without it, the U.S. would lose valuable insights into China’s technological advancements. Denis Simon, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill specializing in technology strategy in China, stressed the need to negotiate a fundamentally new agreement while keeping the issue low-profile to avoid disruption.

“China friend or China foe, the U.S. needs access to China to understand what’s happening on the ground,” Simon said.

However, Anna Puglisi, a former U.S. counterintelligence official focused on East Asia and now a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, believes that science and technology cooperation, once considered the positive aspect of U.S.-China relations, has changed.

She highlights the importance of transparency and reciprocity, urging the U.S. government to thoroughly evaluate the benefits gained from the agreement beyond mere meetings.

“There has to be transparency and there has to be reciprocity,” she said, adding that, “And the U.S. government needs to do a full accounting of what have we gotten out of this besides a couple of meetings.”