As the skies across America explode with color and sound this Fourth of July, one might wonder how and why this clamorous tradition came to be. Like most of us, fireworks’ roots are not in the US. They originated on the other side of the globe, and evolved — through the input of many nations — to be the dynamic, vibrant expression we look to for big celebrations.

How do fireworks work?

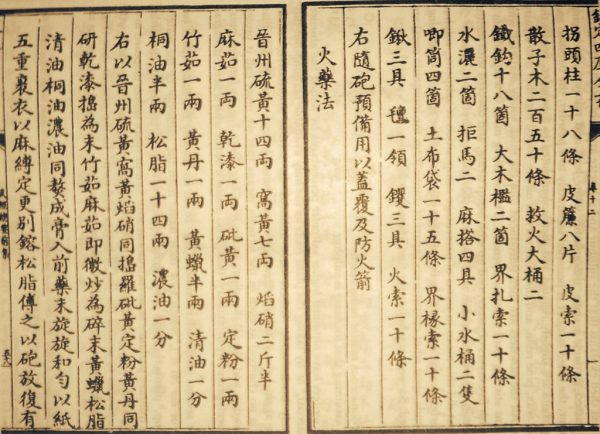

There is a reason fireworks resemble firearms in their activity — their chief ingredient is gunpowder. This black, granular substance was first discovered around one thousand years ago in China, as legend has it, by alchemists aiming to invent an elixir for immortality. A mix of sulfur, saltpeter and charcoal was found to have explosive properties, and was called huo yao (火 藥), or flaming medicine.

Ignited by a spark, the sulfur melts onto the saltpeter (potassium nitrate) and charcoal, causing them to burn. Energy and gas are generated by the combustion, and if the formula is confined — rather than loose — it creates an explosion. If the container has an outlet, the explosion can launch a controlled projectile. If it does not, it can be a dangerous blast for everything within range.

The size of the granules determines the speed of combustion, with coarser particles burning more slowly than fine powder. This factor is used to control the timing of fireworks, but what about the special effects?

The fantastic light show is a matter of added elements that, when heated, release different wavelengths of light. Sodium yields a yellow glow, while blues come from copper, and reds from strontium. Titanium and magnesium give off a bright silver light, and also generate sparks and flashes. Iron has a similar effect in gold.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Whistles and booms depend largely on the container. Much like a wind instrument, the size of the opening can change the sound of a whistle. A closed vessel will explode with a bang, because the gas has nowhere to escape to.

Evolution of Fireworks

The earliest fireworks, however, preceded gunpowder. In ancient China, it was believed that loud noise could ward off evil spirits. Bamboo, a plentiful resource in Asia, has pockets of air trapped between the nodes of the stem. Exposed to extreme heat, the air expands, causing the bamboo to burst; so the sticks would be placed in a fire to produce a series of loud popping sounds.

Adding the discovery of gunpowder made the effects much more dramatic, and eventually led to the use of blasted projectiles as weapons — such as guns and cannons — around 1200 AD. The spectacular aerial display from these explosive rockets became a notable feature for fireworks, which spread around the world as the highlight to grand celebrations.

After their introduction by Italian merchant Marco Polo in 1295, Europe became enthralled with this explosive entertainment. Italians are credited for the addition of color, and schools sprang up across Europe for the art of pyrotechnics. Fireworks grew more elaborate with the friendly competition among leaders to produce the best fireworks shows.

Royalty employed fireworks for special occasions, like King Henry VII’s wedding in 1486, and the coronation of James II two centuries later in England, generating spectacular, legendary displays. James was so pleased with his show that the royal firemaster, or pyrotechnics expert, received knighthood.

The birth of Peter the Great’s son merited a five hour show in Russia. In honor of his grandson’s wedding to Marie Antoinette, French King Louis XV hired the Italian Rugieri Brothers for an extravagant production at Versailles in May 1770. Some of the 20,000 rockets reportedly reached a height of 300 meters.

As fireworks danced around Europe, they did not miss the boat to the New World. Legend has it that Captain John Smith launched the first fireworks in Jamestown – the first English settlement in North America – in 1608. Early colonists appear to have enjoyed pyrotechnics to the point of disturbing the peace, as an ordinance was issued in 1731 to prohibit their unruly use in Rhode Island.

Independence Day fireworks

On July 4, 1776, 15 months into the Revolutionary War, the Second Continental Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence.

While it would be another seven years before the colonists won their war for freedom from England, this anniversary has been celebrated — as predicted by John Adams in a letter to his wife — as the “most memorable in the history of America.”

“… I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade…bonfires and illuminations [a term for fireworks]…from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.”

All things considered, what could be a more fitting celebration for the anniversary of our melting pot of a nation, than a fiery display handed down from our collective ancestors?