Amidst the beauty and serenity of the countryside landscape, surrounded by books, wine, and farming fields, dwelt Tao Yuanming (陶淵明), a famous poet who lived during China’s Six Dynasties era around 1,500 years ago.

The great-grandson of a prominent military commander and governor, Tao held various government posts for 13 years towards the end of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420).

However, amidst the political dysfunction that characterized China of the time, and driven by commitment to his principles, Tao found himself compelled to resign multiple times throughout his career. Later referring to himself as Tao Qian (陶潛, “Tao the Hidden”), he instead dedicated himself to the pursuit of truth and authenticity.

Tao’s journey is abundantly reflected in plain yet penetrating verses that, through their depictions of natural scenery and rustic settings interwoven with direct reflections on the human condition, allowed Tao to craft an enduring — and unique — message of spiritual beauty in his lifelong search for the Dao (道) or Way.

Returning to the plains and fields

Tao Qian’s surviving works are comparatively few, numbering around 130 poems and texts. However, he is considered the main pioneer of the “fields and gardens” (田園詩) genre of Chinese poetry, in which human thoughts and actions are conveyed indirectly, through subtle and wondrous descriptions of nature.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

A typical example can be found in Tao’s series of poems titled “Returning to Life in the Plains and Fields” (歸園田居).

In No. 3 of the collection, he writes of how “the weeds are many and the sprouts are few,” in his agrarian settlement by “South Mountain,” yet he happily accepts the challenge to clean up his garden early in the morning and retire late at night, “carrying a hoe under the moon” on his way home. (晨興理荒穢,帶月荷鋤歸。)

The poem drives to a point, with Tao writing, “the road narrows as the weeds and brush grow thick/the evening dew dampens my clothes.”

Finally, the poet draws out his deeper feelings: “Even with my clothes dampened I do not fret/as it shall not turn back my will.” (但使願無違。)

In the first poem of the collection, Tao Qian gives something of a manifesto for his break with the political world, writing, “From young I was at odds with the secular ways/By nature I love the mountains and hills/By mishap I landed in the worldly maze/Once in it was three and ten years.”

Comparing himself to a “caged bird pining for old woods” or a “ponded fish yearning for former depths,” he goes on to describe himself “maintaining my honesty” and taking refuge in the land.

The rural dwelling he retires to is not just attractive for its abundant space and foliage, but more importantly without the spiritual pollution of “the complicated world.”

“Having long been in confinement, I return now to the natural state.” (久在樊籠裡,復得返自然。)

Describing the indescribable

As a scholar and official, Tao Qian doubtlessly studied the Confucian classics, and while writings do not endorse any particular faith, his entire writing style and interests suggest an affinity for the Daoist philosophy of following the natural way and returning to the original, true self.

Tao also lived in a time when Buddhism, an Indian religion, was spreading through China via the Silk Road in the north and west, as well as via the sea ports to the south. Buddhist teachings of abandoning secular desire and attachment also seem relevant in the context of Tao’s poetry. He tempers human desires, feelings, and anxieties by depicting our struggles through natural scenes and images, which works together to bring about a sense of calm and stillness.

Indeed, Tao and his family sometimes suffered poverty and hunger on account of his frequent changes in employment with the authorities. Yet he took the hardships as inevitable, even joyful, aspects of a life lived with the right attitude.

In the twenty-part series, “Drinking Wine,” Tao famously remarks about his ability to mentally remove himself from “the noise of horse and cart traffic” despite “setting up my hut among men.”

After the heart’s flight to a better state “has the earth move of its own accord” (心遠地自偏), the narrator sees himself “picking chrysanthemums by the eastern hedge, while South Mountain is seen (or perhaps simply materializes) in a leisurely fashion.” (採菊東籬下,悠然見南山。)

Tao continues with the image, having left the clamor of traffic far behind. “The aura of the mountain is beautiful with the coming of night/with flying birds joined in return.”

And ends with an observation, though no conclusion: “In here the truth is to be found/But I forget the words once I try to explain.” (此中有真意,欲辯已忘言。)

A journey to the Peach Blossom Spring

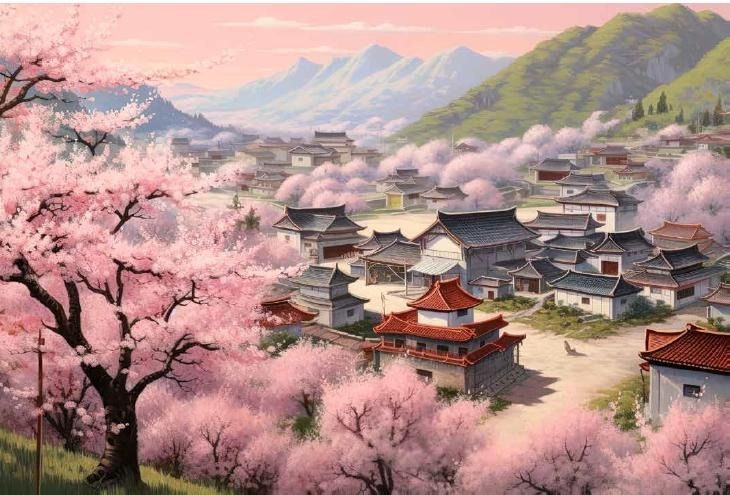

What is perhaps Tao Yuanming’s most famous work is not even a poem, but a short parable called the “Record of the Peach Blossom Spring” (桃花源記) — which in Chinese has become a word similar to “utopia” or “dreamland.”

Viewed from Tao’s vantage point, the story is a lesson of external pursuit versus that which can be seen only by the mind’s eye and a pure heart.

A fisherman, as the story goes, was sailing along a river until it narrowed into a creek with nothing on either bank but peach trees in full bloom. When the man could sail no further, he disembarked and followed the stream through the dense peach forest. Eventually, he discovered its source, a sizable crevice in a towering cliff of rock.

Curious, the fisherman ventured into the grotto, finding that it was spacious enough for a man to pass. The space widened and opened to reveal a small but thriving village, with lush trees and fields among the fine buildings. Happy residents greeted the fisherman courteously, and invited him to stay a few days.

The guest was shocked to learn that this hidden village was completely secluded from the outside world, as its founders had fled here centuries prior to escape war and tyranny.

When seeing the fisherman off, the locals advised him not to tell others of their existence, saying it was “not worth mentioning.”

Of course, the fisherman did not heed their request, and, returning to his boat through the grotto, left markers along the path so he could retrace his steps. He reported his discovery to the local prefect, who sent a man to accompany him back to the Peach Blossom Spring.

But the marks had disappeared, the two got lost, and they never found the way.