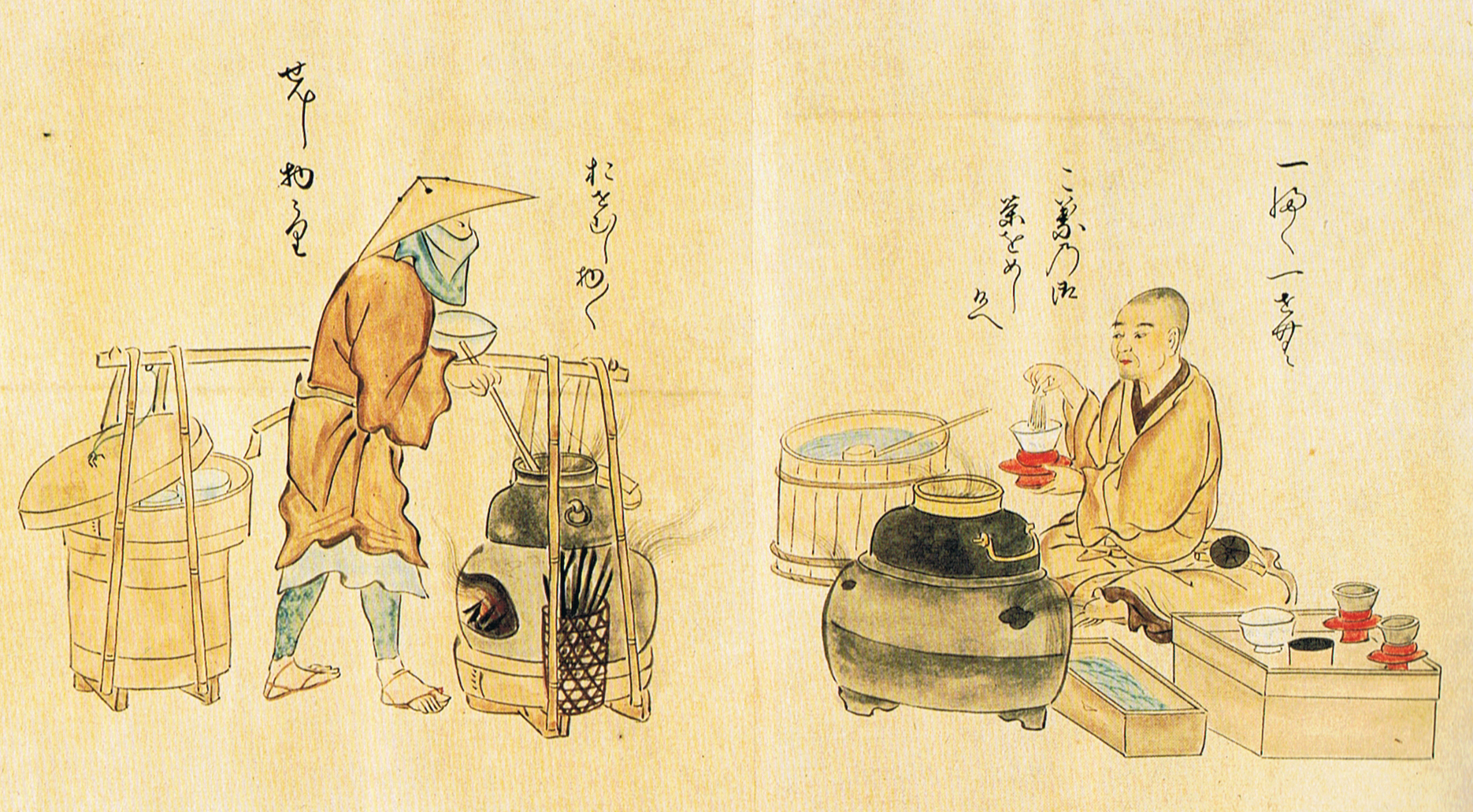

First discovered in China, tea was spiritually embraced in Japan for its beauty and simplicity, and the tea ceremony became an enduring element of Asian culture – present in everything from protocols at imperial courts to common gatherings.

The art of making and serving good tea has been perfected over hundreds of years, with the most delicate and fragrant results stemming from purity of spirit. If your hectic life craves serenity and clarity, a ritual tea ceremony may be just the thing to nurture mindfulness.

“The Way of Tea”

Tea was initially used as a medicine and as an aid to combat drowsiness during meditation. As the Chinese mastered tea cultivation and production, the infusion began to permeate all spheres of society, becoming a staple beverage by the Tang dynasty – China’s cultural golden age.

This was also the peak of cultural exchanges between China and Japan. In the 9th century, a Japanese monk studying Buddhism in China returned to his homeland with some green tea for the Japanese court.

The stimulating beverage that resulted from steeping the leaves in hot water quickly became the drink of choice among the Japanese aristocracy. Although interest in tea gradually waned, it resurfaced several years later with staying power.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

In the 12th century, a monk named Eisai returned from China with seeds for propagating tea and a method for preparing matcha.

Eisai also introduced Zen Buddhism to Japan and is considered to be the founder of the Rinzai Zen school, a tradition that draws from Indian Mahayana sutras and the Chinese Chan school. Among its philosophies is the thought that enlightenment can be reached in the course of performing ordinary everyday actions, such as making and drinking tea.

The preparation of tea then became a spiritually significant enterprise, giving rise to a distinctive Japanese ritual known as chadō (茶道) or “The Way of Tea,” or more commonly referred to as the Japanese tea ceremony.

Mindfulness and insight

There is a deep philosophy behind the solemnity and finesse of this ritual, based on various spiritual concepts.

Among them is the Daoist belief that “The slow overcomes the fast,” which alludes to the power of patience and self-control against hasty and mindless actions. In the tea ceremony, this is reflected in the slow and gentle movements of the person preparing and serving the tea.

Another concept is Ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会) which refers to the unique quality of each moment. Similar to the popular saying from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man,” this Japanese thought embraces the impermanent nature of life and the importance of appreciating the here and now. A gathering can never be replicated, even if the same people gather in the same place.

The tea ceremony also embodies the concept of omotenashi (御持成) or wholehearted hospitality. Deeply rooted in Japanese culture, omotenashi is the philosophy of serving others with humility and sincerity, doing things openly and in a thoughtful manner.

“Though you wipe your hands and brush off the dust and dirt from the vessels, what is the use of all this fuss if the heart is still impure?”

Tea master Sen no Rikyū

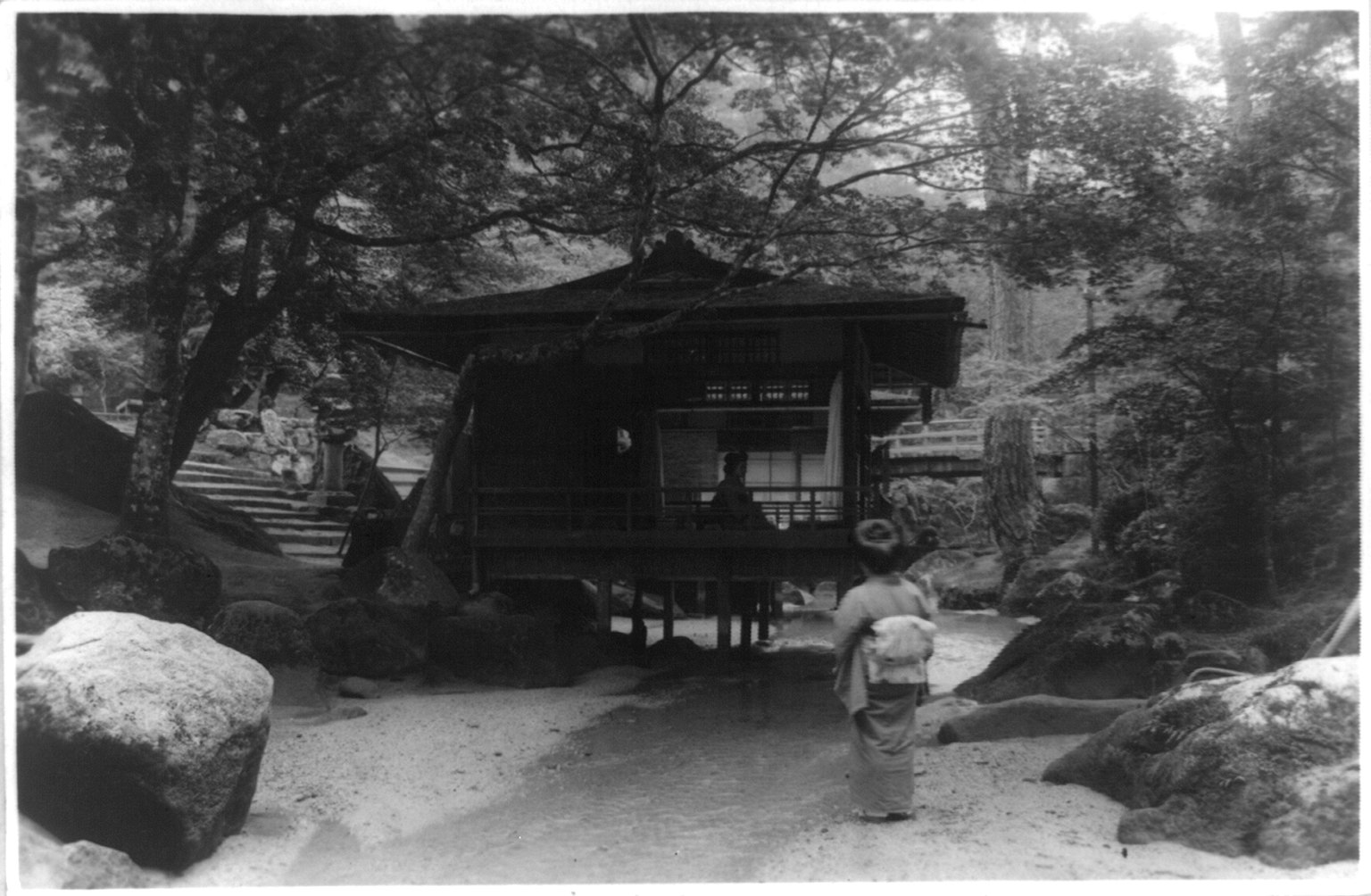

Wabi-sabi is reflected in the tea ceremony, too, specifically in its aesthetics. This philosophy embraces rusticity and modesty, and establishes three principles of beauty: imperfection, impermanence and incompleteness.

Wabi-sabi influenced decor consists of simple objects that reflect the humble beauty of nature, such as ikebana – a minimal floral arrangement, and a carefully chosen scroll of calligraphy. Even the tea service is earthy and modest.

Recipe for a tea ceremony

Ocha (お茶) – tea leaves: High quality, loose leaf tea has a uniform appearance and a distinctive aroma. Black tea smells earthy and sweet, green tea smells grassy, and herbal tea exhibits the characteristic aroma of its plant material.

Mizu (水) – water: Water quality is critical in making or breaking your brew. Aim for a neutral pH, minimal hardness and no chlorine or other impurities. Spring or distilled water is recommended, but filtered tap water is also acceptable.

Kama (釜) – kettle: Water should be heated on the stove, preferably in a traditional cast iron tea kettle – called a tetsubin. These heavy vessels will last a life-time and bring a timeless charm to your tea ceremony. They hold heat extremely well and improve the flavor of filtered water.

Hishaku (柄杓) – tea scoop: A traditional Japanese tea scoop made of bamboo allows you to appreciate the physical properties of the tea before brewing.

Kyusu (急須) – teapot and chawan (茶碗) – tea bowls): While in the West we tend to use large sturdy mugs for both brewing and sipping, Eastern tradition favors tiny tea bowls filled from little pots for the best taste flavor and experience.

Yuzamashi (湯冷) – fairness pitcher: Loose leaf tea can be brewed multiple times, and the aroma and taste of the tea changes not only from brew to brew, but even within the same pot the intensity of the flavour varies.

Since the bottom tea is more concentrated, a fairness pitcher is used to obtain a uniform tea. Immediately after infusing the tea in the teapot, it is strained into the pitcher – from which it is poured into the cups.

Conducting a tea ceremony

- Choose a clean, orderly space where you can perform the ritual frequently. Gather your utensils and designate a specific place for each, according to its function.

- Clear your mind, and fill the teapot (using your scoop) up to one third full with loose tea leaves.

- Heat the water to the appropriate temperature for the tea you are serving.

- Pour the hot water into the teapot in a small circular motion to gently awaken the leaves, filling the pot about three quarters full. Quickly discard this water, as its purpose is to remove dirt and dust from the leaves and encourage them to start opening.

- Refill the teapot to its full capacity, and let the tea steep for the recommended time.

- Strain the tea into the fairness pitcher, noting the distinctive color of each brew.

- If you have guests, serve them first, encouraging them to experience the aroma and taste of each sip.

- Repeat the brewing process until the leaves lose their flavor (about five times).

- Incorporate the tea ceremony into your weekly routine. Remember that each moment is unique and unrepeatable, and that only by being present can you see its beauty.