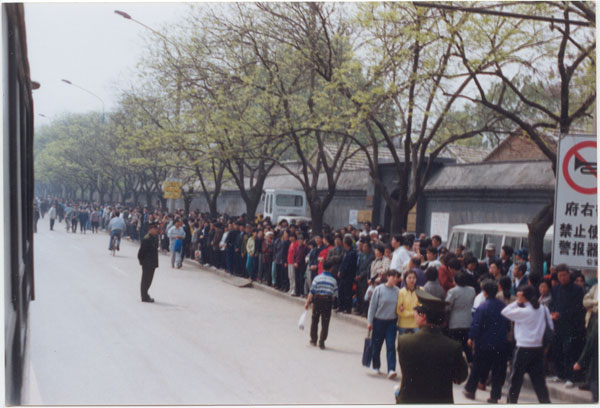

In the early morning of April 25, 1999, crowds of people began filing into the roads leading to and around Zhongnanhai, headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Beijing. They were largely silent, carrying no posters or shouting slogans. As more arrivals filled the area around the leadership compound, police issued instructions to the group, which duly obeyed. Most sat down and began to meditate.

The estimated 10,000 to 18,000 demonstrators who went to Zhongnanhai that day were practitioners of Falun Gong, a Chinese spiritual discipline that incorporates meditation exercises and a body of moral teachings centered around the core principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.

For nearly seven years, Falun Gong — also known as Falun Dafa — had been freely taught and practiced throughout China. Tens of millions of people had taken up the practice, including high-ranking members of the Party, government, and military. Senior leaders praised Falun Gong for its health benefits and positive contributions to the nation.

But in the previous months, the authorities’ attitude toward the practice and its adherents took a noticeable turn for the worse. Police had harassed meditators, and media outlets began running articles defaming Falun Gong and misrepresenting its teachings. And on April 23, police in Tianjin, a large port city near Beijing, had arrested 45 practitioners for protesting an article that claimed the discipline was harmful.

More than 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners gathered on Fuyou Street in Beijing on April 25, 1999, to peacefully appeal for fair treatment. (Image: Minghui.org)

Just a decade earlier, the CCP had deployed troops to Beijing, killing thousands of student demonstrators at Tiananmen Square following Zhongnanhai’s fateful decision to label the youths “violent rioters.”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

With the media environment worsened, many Falun Gong adherents feared that their faith might soon meet with similar political treatment. They opted to make their case before the authorities before it was too late.

Mounting pressure

An article published in Tianjin Normal University’s Youth Reader magazine was penned by He Zuoxiu, a far-left public intellectual from the Chinese state’s Academy of Sciences.

Though nominally a physicist, He’s writings were characterized by radical Marxist polemics, such as one article that raised eyebrows for its criticism of quantum physics as a “bourgeois science.”

But behind He’s dubious scientific ideas were real political connections: He was a relative by marriage of Luo Gan, a senior police official and an ally of China’s then-leader, Jiang Zemin.

As early as 1996, Chinese police agents had gone undercover to investigate Falun Gong, with orders from Luo Gan to uncover evidence of the practice’s supposed political agenda. None would be found, but the security services persisted. They stepped up their harassment of practitioners, breaking up their meditation groups in parks and other public spaces, or even detaining individual adherents.

But not all in the leadership were in favor of taking a hard line. Qiao Shi, then China’s third-most powerful official and the chairman of the National People’s Congress, launched his own investigation into Falun Gong. The report published by his team in 1998 concluded that the practice brought “hundreds of benefits and not a single harm” to the country.

And when the Falun Gong practitioners gathered before Zhongnanhai on April 25, they were greeted by China’s Premier Zhu Rongji, who invited several adherents into the compound. Zhu assured them that the state would guarantee their freedom of belief and assembly, as guaranteed in the Chinese constitution.

Former CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin (R) and Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji. The two officials differed in their approach to the Falun Gong spiritual practice. (Image: NTDTV)

But the coming persecution of Falun Gong — the biggest political campaign since the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s — was already in the works.

Jiang Zemin had reportedly driven around Zhongnanhai in his private car to view the practitioners gathered there, and remarked with alarm that they were more disciplined than the Chinese military.

According to various accounts, Jiang had multiple reasons for deciding to eradicate Falun Gong, from personal jealousy of the practice’s popularity, to seeing what he envisioned to be a quick campaign as a means of boosting his political prestige. But what is certain is that under Jiang’s watch, the CCP declared Falun Gong’s spiritual beliefs, which are rooted in traditional Chinese faiths, anathema to its own atheist communism.

Propaganda epicenter in Wuhan

Jiang gradually recruited supporters in the CCP for the upcoming campaign. One of those who quickly discerned and seized the opportunity for promotion was Zhao Zhizhen, then director of the state-run Wuhan Television Station.

In late June, at the behest of Luo Gan, Zhao sent a three-man film crew to the northeastern Chinese city of Changchun, the hometown of Falun Gong’s founder, Li Hongzhi. The team produced a six-hour video defaming Li.

According to Minghui.org, a website that documents the persecution of Falun Gong, Wuhan Television’s film attacking the practice and its founder was played at the Politburo meeting at which Jiang Zemin intended to force through his plans for the anti-Falun Gong campaign. This helped him gain consent from other CCP leaders to begin the persecution.

Filled with untruths, the film produced by Wuhan Television played a crucial role in damaging Falun Gong’s reputation in the summer of 1999.

On June 7, Jiang ordered that a special commission be set up with the sole purpose of coordinating anti-Falun Gong efforts. Three days later, the CCP established the Central Leading Group on Dealing With Falun Gong, also known as the 610 Office for its founding date. Until it was nominally abolished in 2018, the Office was endowed with the extralegal authority to carry out the persecution of Falun Gong at all levels of the Chinese government and in virtually all spheres of life.

On July 20, Chinese police began arresting Falun Gong practitioners on a nationwide scale. More films like those made by Wuhan Television were produced and played around the clock to turn the Chinese people against the practice.

A Falun Gong practitioner holds a banner at Tiananmen Square reading ‘Truth, Compassion, Tolerance,’ the core tenets of the practice. A policeman approaches to arrest him. (Image: Falun Dafa Information Center)

A pernicious legacy

Largely underreported, the persecution of Falun Gong has had broad and lasting consequences for Chinese human rights, politics, society, and even international relations.

The casting of 70 million to 100 million Chinese — the government’s estimated number of Falun Gong adherents in 1999 — as following what the CCP claimed was a “heretical religion” created countless human tragedies overnight. Over the course of the persecution, millions of people have been arrested for practicing Falun Gong.

Many have been tortured, made to perform slave labor, psychologically abused, or injected with unknown drugs. There is currently no way of knowing how many Chinese have died because of the persecution, though Minghui.org lists several thousand confirmed deaths.

Starting in the year 2000, the Chinese organ transplant industry began to see rapid development. From 2006 onwards, human rights investigators have produced increasingly sophisticated reports showing that thousands of prisoners of conscience have been murdered for their organs in Chinese hospitals. The majority of the victims are believed to be Falun Gong practitioners.

Wuhan’s Tongji Hospital was one of the first medical facilities implicated in carrying out forced organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners.

Spending for the People’s Republic of China’s domestic security apparatus runs in the hundreds of billions of dollars, owing to the massive requirements of operating the world’s most sophisticated and well-staffed surveillance state and censorship forces.

The CCP has been enforcing its totalitarian ideology and rule across the entire Chinese population with an advanced infrastructure of mass surveillance and censorship. (Image: YouTube / Screenshot)

Much of this system was built up in the 2000s as a result of the sudden need to carry out the anti-Falun Gong campaign on a national scale. In the late 2000s, the domestic security budget outstripped spending on the regular Chinese military.

Over the years, the CCP expanded its persecutions to other groups and the general public, while intensifying indoctrination programs. The persecution of Uyghur Muslims follows many of the same patterns as the anti-Falun Gong campaign.

Today, these pernicious influences in the realms of propaganda and human rights abuse can be seen in the Communist Party’s treatment of the CCP coronavirus pandemic.

The CCP covered up the outbreaks, and spread propaganda to convince the Chinese people and the international community of its victory over the disease, even as reports indicate that it continues to spread and worsen. Instead of admitting its fault, the CCP has shifted blame for the new wave of infections to Chinese nationals returning from abroad, as well as denying that the virus originated in Wuhan.

Follow us on Twitter or subscribe to our newsletter