Intense blue has always been an important color in traditional artwork as a means of symbolizing heavenly beauty, majesty, and perfection. One blue pigment is often considered to be the most expensive ever created, costing more than its weight in gold.

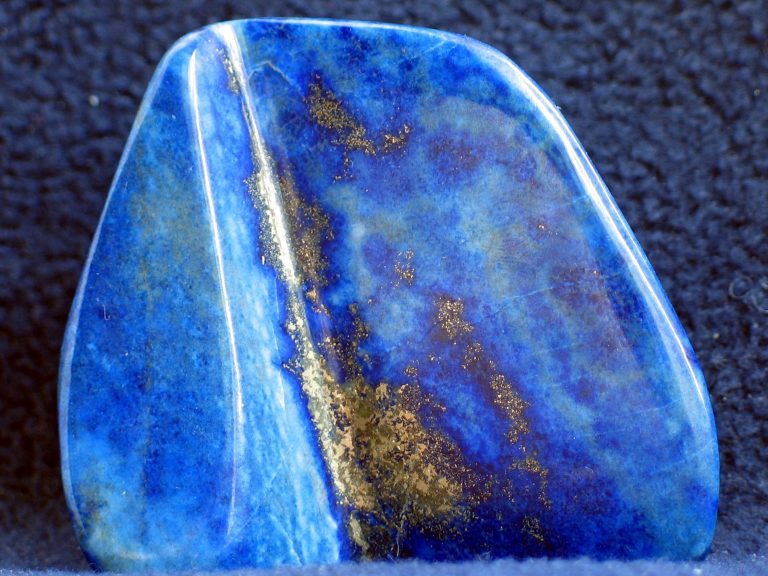

Ultramarine is a pigment derived from the crushed rock of lapis (stone) lazuli (azure, or blue). The deep blue hue is due to the presence of high quantities of lazurite, a blue sodalite mineral. Lapis lazuli consists primarily of lazurite, with white veins of calcite and golden splashes of pyrite, which combine to make an opalescent pigment.

A long history

The mineral pigment was used as far back as the sixth century AD, on ceramic figures depicting ancient Sogdians (Silk Road merchants) discovered in the Wei Dynasty Tombs in Luoyang. The Thousand-Buddha Grotto in Guangyuan, which dates from the 7th to 10th centuries (Tang Dynasty), is adorned with wall murals where the lazurite was also found.

Miniatures from the Persian and Mughal periods peaked in the 15th and 16th centuries. In his outstanding miniature work, Kamal-ud-din Behzad (1450-1535) made great use of the beauty and durability of Lapis pigment. The same beauty of Lapis may be seen in Mughal miniatures, which have not faded over time.

Recent findings show that Lapis Lazuli pigments were also used in the production of illuminated manuscripts. In Dalheim, Germany, a middle-aged woman was buried in a 9th to14th-century church-monastery complex and within her dental calculus, Lapis Lazuli–derived ultramarine pigment was discovered.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The pigment was identified as a powder consistent in size and composition with Lapis Lazuli–derived ultramarine pigment. It seems that the lady was most likely a painter of highly decorated religious manuscripts. She is the first direct proof of a religious woman in Germany using ultramarine color.

The gemstone

Afghanistan has long been the primary supplier of Lapis Lazuli. It was mined in Badakhshan’s Sar-i Sang and Shortugai caves as early as the 7th-millennium BCE. Marco Polo once wrote, “There is a mountain in that region where the finest azure [Lapis Lazuli] in the world is found. It appears in veins like silver streaks.”

Like other blue gemstones, lapis lazuli is spiritually associated with a higher consciousness. It has often been used in meditation and is believed by some to facilitate the opening of the third eye, or sixth chakra. An eye carved from the stone and set in gold is considered in Egypt to be a powerful amulet.

Many consider the stone to be a symbol of truth, and justice. In Sumarian myth, Inanna, the goddess of love, visits the underworld to attend her brother-in-law’s funeral, wearing lapis lazuli beads and carrying a rod made of the gem. Upon entering, she was stripped of all her adornments, and thus her power, and was sentenced to death.

Inanna was eventually rescued, but her sister insisted that someone else must take her place when she left. Inanna found that her husband had not mourned her absence, and was happily engaged with slave girls; so she chose him, rather than any of her servants who had mourned her properly, to be sent to the underworld in her place. Justice served.

Western application and modification

After its introduction to Europe by Italian merchants during the 14th and 15th centuries, the pigment became known as ultramarine, from the Latin ultramarinus, meaning literally “beyond the sea,” but it could also allude to the intensity of the color, which appears to shimmer like the moving water once applied to canvas.

The extraction process was laborious and costly, making the product prohibitively expensive for working artists of the Renaissance, and it was usually reserved for only the holiest paintings. Even so, it is said that Michelangelo left his painting The Entombment unfinished because he could not afford the precious pigment. Rafael built up his blues with less expensive pigments and only applied ultramarine on the final layer.

With the incentive of 6,000 Francs to develop a synthetic ultramarine, a French Chemist – Jean-Baptiste Guimet, and a German professor – Christian Gmelin, both stepped forward to claim the prize. Of the two, Guimet was determined to have discovered his solution first, and his artificial pigment was developed in 1826 to become the widely accessible French ultramarine.

Because the synthetic pigment lacks the natural mineral impurities, it offers an even bolder, purer color, which some find offensive. Painters like Andrew Wyeth preferred to stick with tradition. He ground his own mineral paint, despite the great expense, to achieve the subtly softer color.

As art critic John Ruskin once said, “The blue colour is everlastingly appointed by the Deity to be a source of delight; and whether seen perpetually over your head, or crystallised once in a thousand years into a single and incomparable stone, your acknowledgment of its beauty is equally natural, simple, and instantaneous.”

Ila Bonczek contributed to this report.