The United Arab Emirates (UAE) will switch to a four-and-a-half-day work week on January 1, 2022, according to a statement released on Tuesday by Latestly. The UAE is the world’s first nation to adopt a shorter weekly unit of time. The initiative is intended to bring the UAE into line with global markets, but it pits it against Gulf Arab rivals that retain a Friday-Saturday weekend.

The majority of countries operate on a seven-day week system even though the natural order does not dictate weeks.

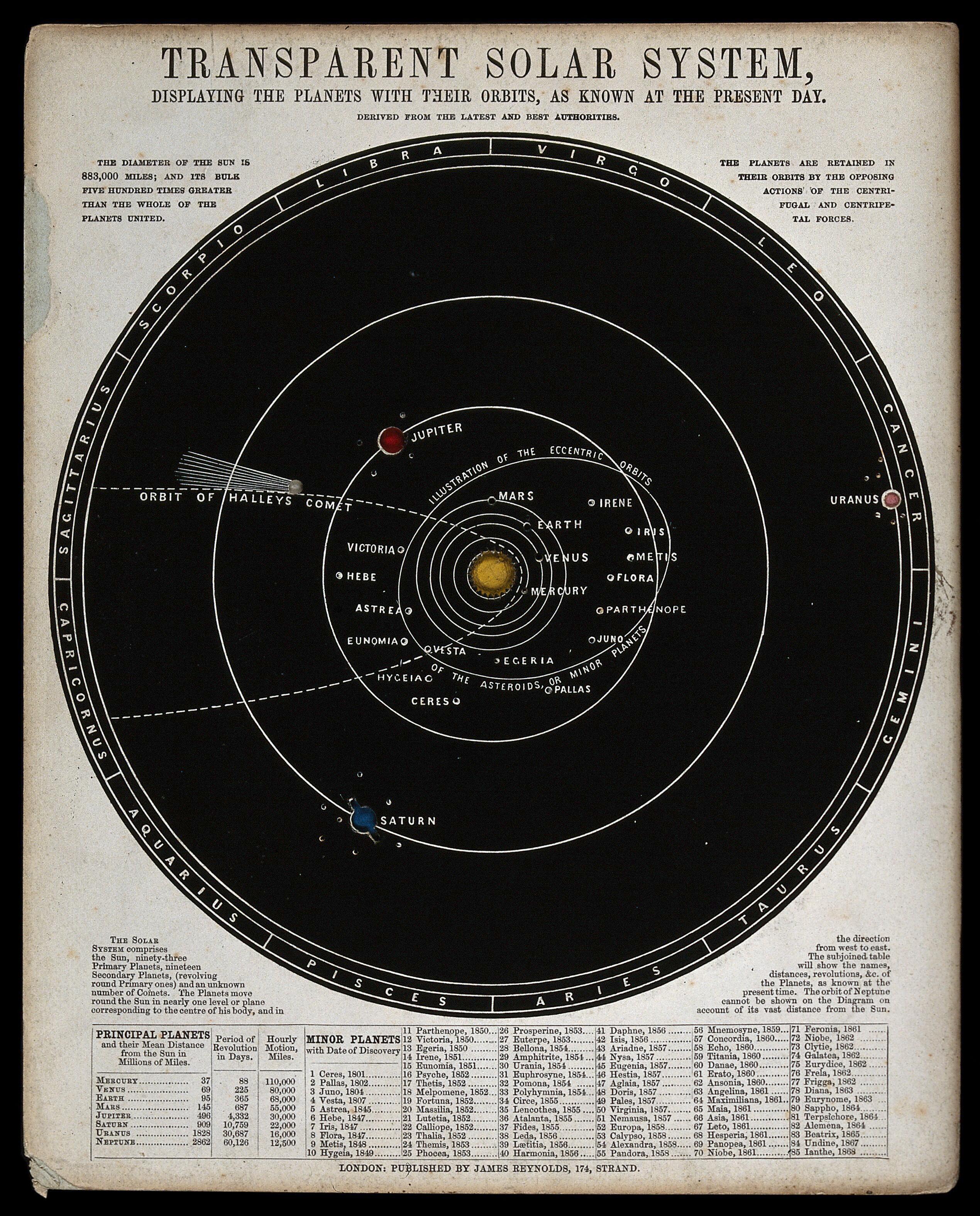

The Gregorian calendar, like many others, is based on lunar phases. Time is split into groups measured by astrological body motions. While it takes a “year” for our planet to complete one full solar orbit, with each “day” representing one turn on its axis, a “lunation” is 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes, and 3 seconds long.

The Babylonians were the first to round the Moon cycle to 28 days and split it into four 7-day intervals. They employed leap days to keep up with the Moon’s phases.

The present names of the weekdays come from the Romans, who calculated the distance between Earth and the classical planets based on their speed across the sky. The fastest-moving planet was thought to be the shortest distance from the Earth, while the slowest was believed to be farthest away.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Select people have long tried to alter the status quo. In 1793, the French Revolution created a calendar with three 10-day “decades,” but ultimately failed to abolish the seven-day week. In 1929, the Soviet Union attempted a five-day work week with one day off, but it also failed.

In a 1944 discussion on calendar reform, a member of the British Parliament made the following observation: “It is bad enough to be born on April 1, but to have one’s birthday always on a Monday would be perfectly intolerable.”

The Seven-day Week And How We Experience Time

Reporter Joe Pinsker from The Atlantic interviewed historian David Henkin, following the publication of his book, The Week: A History of the Unnatural Rhythms That Made Us Who We Are.

Henkin says there was a big change in how people thought about the week in the 19th century. The week became a lot more important in people’s lives and it didn’t make a difference if it was Sunday, the day of rest, or not. He said that it evolved into what has become, in some respects, the most stable calendar unit.

Now, if it happens that one believes it is a Tuesday but it turns out it is actually Wednesday, one may feel bewildered. Henkin reasons that this is because of urbanization and a social phenomenon where individuals want to be able to plan with others, whether for business or social reasons.

He pointed out that in the past, folks who lived on farms didn’t need to coordinate activities with those whom they didn’t see regularly. For them, the day of the week was less important; whereas today, a lot fluctuates from one weekday to the next. Schedules for work, entertainment, custody arrangements, and many other things are all based on our seven-day cycle.

When asked how this change makes time feel different, Henkin admitted that it was hard for him to prove as a historian.“When we are more attuned to this cycle because it’s shorter than a month, it feels like time moves much more quickly. When our Mondays are different from our Tuesdays and our Wednesdays, it does kind of feel like all of a sudden; It’s Monday again?! You can see in 19th-century diary entries that, more and more often, people describe this feeling by referring to how another week has come and gone.”

Henkin speaks about attempts undertaken 100 to 150 years ago to ‘alter’ the annual calendar. The reasoning for this was the reformer’s intention to ‘tame’ the week—to make it more logical. As part of their sales pitch, regarding solving a broader problem, Henkin said, “saying today is Tuesday, November 16, 2021, is technically a redundancy—there is no November 16, 2021, that isn’t also a Tuesday.”

“When people mix up weekdays and dates—say they mistakenly schedule something for Wednesday, November 16, which might not exist in a given year—it can cause all kinds of confusion.” Some offered a solution of making the calendar so that November 16 is always a Tuesday and that the year had 364 days that always had the same weekday attached plus a handful of “blank days” at the end of the year that doesn’t count as part of any seven-day week.

Reforms like these were backed by businesses in the United States, as well as scientists. According to Henkin, this was the time when the international date line and time zones were set up. Reform groups were able to get governments to agree with Greenwich Mean Time.

Still, this reform movement failed. Why? Henkin stated that “the main answer is a religious answer because no Christian, Muslim, or Jew who’s attached to the idea that you can count seven-day weeks all the way back to creation is going to think that you can just move it around.”

“Also,” he said “I’m a practicing Jew, and it would really mess up my life if what I had to observe as Saturday or as Wednesday wasn’t what other people thought was Saturday or Wednesday. But a lot of other people are attached to the weekly calendar for nonreligious reasons, despite knowing it’s not real. Once people got used to thinking of Tuesdays or Wednesdays as real things, it’s not surprising that they were hesitant to dispense with that notion,” he said.

Despite the fact that the week is not based on any naturally occurring cycles, it appears to be a curiously perfect amount of time for spacing out certain recurring activities, such as house cleaning or calling a family member. Is it then feasible to say that the week truly captures something important about our natural rhythms? Henkin seems to think so.

“The reason the week has survived is that it happens to be really well matched with things. My hesitation about that is that the things it’s well-matched with seem so historically constructed—like, the question of how often you should talk to your mom wasn’t the same in eras before the telephone. One neurological explanation that’s been suggested is that the seven-day week originated—or, more plausibly, survived—because humans are good at memorizing things up to seven.”

“And then there’s another hypothesis, which I’m a little more drawn to because I’m a historian: that our sense of what is an appropriate amount of time to wait between activities has been conditioned by the week,” he said. There is also the internet which allows individuals to make their own timetables for watching TV, shopping, and reading the news.

When asked whether he thinks the week is fading in importance Henkin replied, “When I began this project, I had the sense that maybe I was documenting the modern experience of the week just as it was about to unravel. But by the end of it, I was less sure about the unraveling.”

“I do think there’s been some attenuation of the week’s power. But on the other hand, writing this book made me feel like the week will likely survive.

What happened earlier in the pandemic is a great example: People were disoriented because they didn’t know what day of the week it was, and that experience was a telling symbol of the unmooring of time,” Henkin said.