Adapted from Erping Zhang’s original video available on YouTube.

Chinese civilization has long viewed excellence in academics as both a matter of pragmatic necessity as well as moral cultivation. Confucius, the ancient teacher and philosopher, exhorted his disciples to study so that their efforts could be put to the best use.

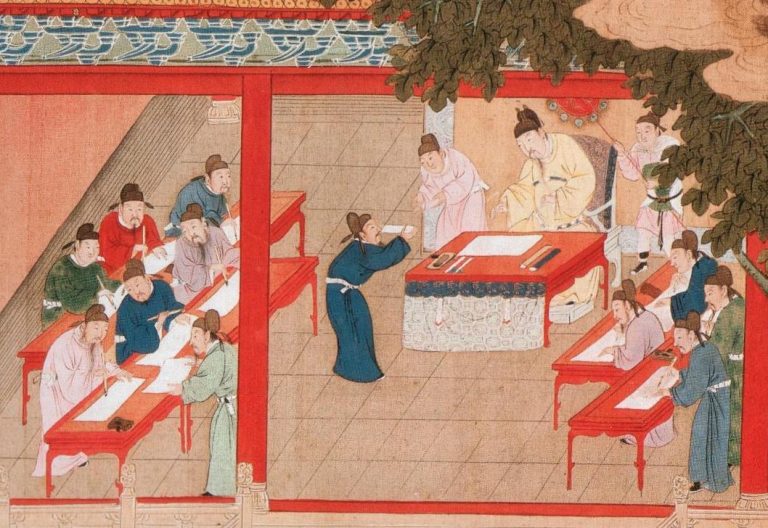

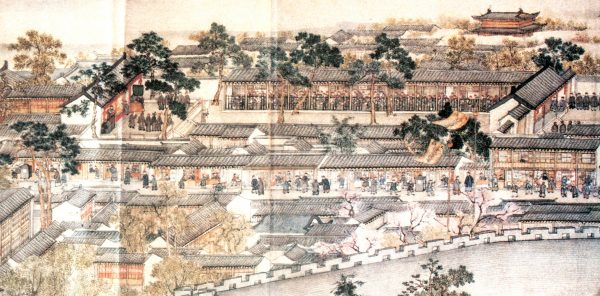

This emphasis on education is perhaps most famously manifested in the imperial examination, or kējǔ (科舉) in Chinese. Designed as a way for the court to gather the best talents throughout the realm to serve in the state bureaucracy, the exams had a profound impact on China’s ancient culture and government.

The first standardized imperial exam dates back to the Sui Dynasty (A.D. 581–618), and was refined in the following Tang and Song dynasties.

Hundreds of years later, China’s imperial exam system influenced the standardized civil service tests devised in European countries, and which are used by schools and universities around the world. In the British Empire, civil servants were called “mandarins” in reference to the officials in China who served a similar role in the bureaucracy.

WATCH ERPING’S OTHER VIDEOS ON CHINA:

- The Story of Chinese Emperors | Tea with Erping

- Legend of the Monkey King and the Journey to the West | Tea with Erping

- Introduction to Chinese calligraphy (Part 1) | Four Arts of Life | Tea with Erping

What was tested?

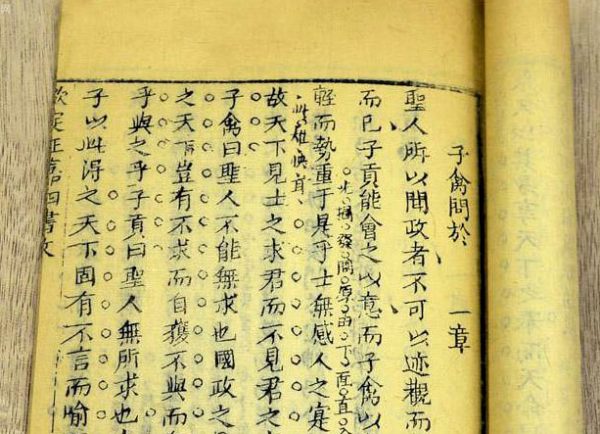

As the benchmark for vetting the administrators who ran China’s vast territory, imperial exams were always based on the Confucian classics and their commentaries on the law and government.

By requiring all of the country’s students to study for this exam, the state was able to unify the empire with a common culture based on the Confucian teachings and strengthen the moral fabric of society.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

In the Tang Dynasty (618–907), Emperor Gaozu added a few items to the exam beyond the Confucian teachings. Knowledge of the imperial edicts, government decrees, and judicial rulings was essential. Aspiring officials were tested on how well they could understand and draft such documents.

Related to this, scholars had to demonstrate the ability to write an eight-part form essay, called ba gu wen (八股文). This was a formalized presentation of ideas with set phrases and structure — one responding to the other, word for word, phrase for phrase, sentence for sentence.

The focus on Confucian classics was reinforced with other metrics. The classics had to be memorized, but, more importantly, well-understood. Clear and coherent speaking skills were also tested, focusing on one’s ability to expound upon the meaning behind Confucius’ words.

READ MORE:

- Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors and the Tomb of China’s First Emperor

- Benefits of Sitting and Meditation in the Lotus Position

- The Ancient Chinese Historians Who Recorded the Truth, No Matter the Cost

- Jun Zi: Confucius’ Teachings on Being a Gentleman

In ancient China, mathematics were well-developed, being divided between “internal arithmetic” , or calculations that could be done mentally, and “external arithmetic” that was to be done with the aid of formulas and algorithms. Statistics and accounting being a necessity for any government, math was also heavily tested in the imperial exam.

Despite the political nature of the exam, the authorities also sought to gauge the moral and spiritual qualities of the applicants. The main way this was done was through assessing their poetry, which was believed to be a window to a person’s true character. The poems submitted would be on themes unrelated to politics, for example, a common subject was purity.

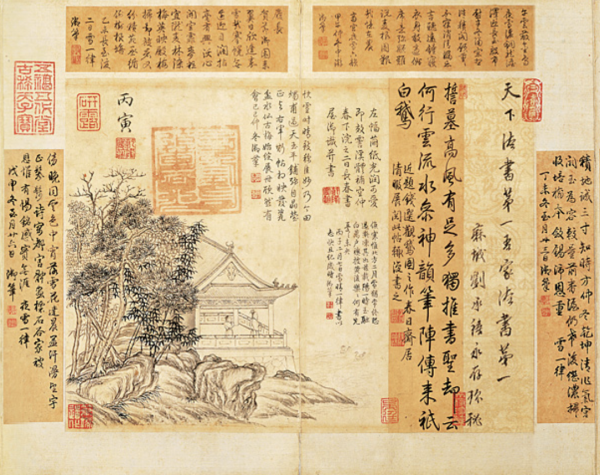

Likewise, the Tang Dynasty reforms also examined test-takers’ calligraphic skill. It was believed that rather than just conveying information, the quality of one’s handwriting reflects the writer’s temperament and character.

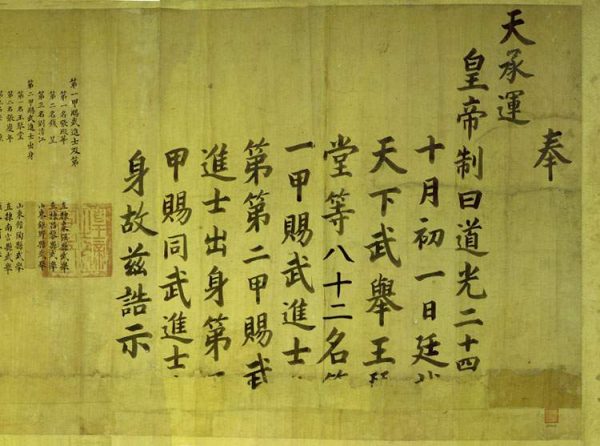

Imperial degrees

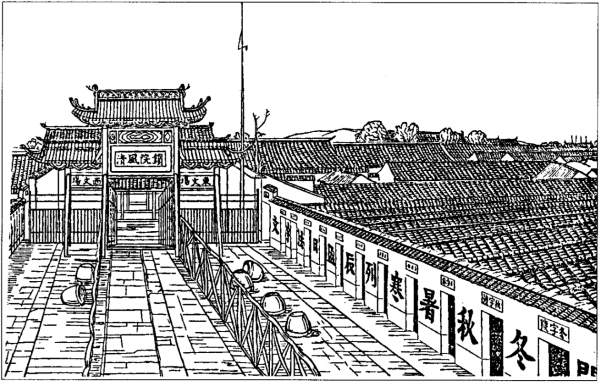

The regular imperial exam was held every year, attracting up to 2,000 candidates per year, producing different levels of scholar-officials, including Xiucai (秀才) or “talent,” Mingjing (明經) or “adept of classics,” and Jinshi (進士), or full imperial scholar. People who pass the highest-level, Jinshi, would become the most important people in China’s educated class, and hold important positions in the imperial court. This level was thus the hardest, with only one or two passing the examination amongst hundreds of candidates.

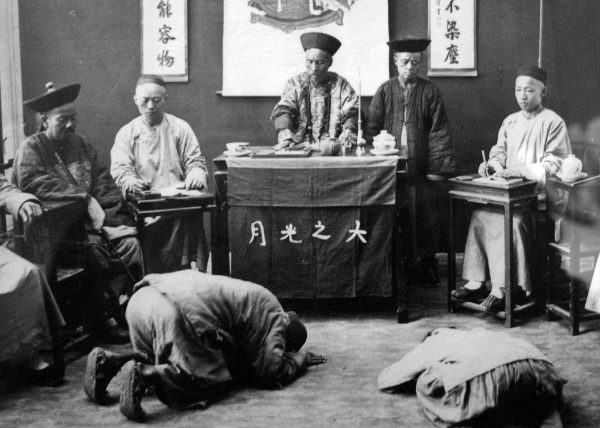

The irregular examination was set up spontaneously by the emperor himself, who would act as the Chief Examiner. The emperor was also known as the “grand tutor” in ancient China. One’s wisdom, virtue, as well as filial and upright character were what the Emperor would look for in this examination.

During the Song Dynasty, the examination was further refined into four levels: The lowest level was the county examination: successful candidates became Xiucai — a distinguished talent, and qualify to take the provincial examination, producing Juren (舉人) — a recommended man or graduate. Juren would become the provincial elite and hold enormous power at the provincial level.

Xiucai would hold leadership positions in their villages or become teachers who maintained the educational system. The third level was the Academy examination producing Gongshi (貢士) — tribute student. Fourth and highest was the Palace examination, which, taking place in the palace, produced the scholars known as Jinshi.

Who could take the exam?

The imperial exams were open to men only, and those of undesirable backgrounds, such as criminals and the children of prostitutes, could not sit for the exam. Apart from this, however, the civil imperial examination did not discriminate by class, allowing even children from poor families the opportunity to become government officials.

In the Song Dynasty, the authorities introduced anonymous grading, identifying candidates by number rather than name so as to avoid bias and corruption.

READ MORE:

- ‘Men Respectful, Women Humble’: The Truth About a Traditional Chinese Idiom

- The Legendary Origins of Chinese Acupuncture

- The Traditional Chinese Garden – A Miniature of Nature, in Harmony With Man

The civil examination system was therefore an important vehicle of social mobility in imperial China. Success in the examination depended on one’s ability rather than one’s social position. This merit-based system is consistent with Confucius’ teachings on proper behavior, rituals, propriety, and relationships. It motivated men of all levels to obtain an education, as successful candidates could not only wear a scholar’s robes, but also were entitled to certain tax benefits and could be spared corporal punishment for some offenses.

‘One of China’s most significant contributions’

Confucius, like the Greek philosophers Socrates and Plato, valued wisdom and virtue over sophist knowledge and skills – a tradition that the imperial examination also aimed to preserve.

But as China entered the modern age, the focus on Confucian teachings and spiritual refinement was criticized, especially as the imperial government grew weak due to corruption and foreign encroachment. Efforts were made to introduce new forms of learning, but the process was far from smooth.

In 1904, the imperial exam system officially came to an end, and less than a decade later, so did imperial rule.

But though more than a century has passed, the significance of the Chinese exam system remains deep. It not only influenced neighboring countries such as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, but also Germany, France, and Britain as the West introduced standardized universal education.

Professor Edward Kracke, a Sinologist, noted that “one of China’s most significant contributions to the world has been the creation of her system of civil service administration, and of the examinations which from 622 to 1905 served as the core of the system.”

As early as the beginning of the 17th century, Matteo Ricci, an Italian missionary in China, reported with commendation in his journal, “the progress the Chinese have made in literature and in the sciences, and of the nature of the academic degrees which they are accustomed to confer.”

French thinker Voltaire made a similar observation in the mid-18th century,

“The human mind certainly cannot imagine a government better than this one where everything is to be decided by the large tribunals, subordinated to each other, of which the members are received only after several severe examinations. Everything in China regulates itself by these tribunals.”

Communist spin

Even after the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), the Republic of China continued to emphasize the importance of education. In his comments on the Five-Power Constitution, founder of the Republic Dr. Sun Yat-sen noted:

“At present, the civil service examination in the [Western] nations is copied largely from England. But when we trace the history further, we find that the civil service of England was copied from China. We have very good reason to believe that the Chinese examination system was the earliest and the most elaborate system in the world.”

Sadly, it is no longer the case for modern China.

The ROC was defeated in mainland China by communist rebels, who founded a totalitarian state under Mao Zedong. After a 10-year hiatus due to the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, the National College Entrance Examination, or Gaokao (高考), was restarted in 1977 and effectively replaced the imperial exam system of old.

But instead of being tested on traditional Chinese norms and cultural values, those who sit for the Gaokao must master Marxism, Maoism, and other doctrines of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

RELATED VIEWING:

- Propaganda — Communist China’s Lethal Weapon | Tea with Erping

- Covid Lockdowns Are Wearing Down the Party State | Tea with Erping

- Why are Chinese Millennials ‘Lying Flat’? | Tea with Erping

Today, every school or college in China is actually run by the Communist Party secretary, not the symbolic president.

And despite the ancient Chinese focus on education, today’s China spends less on education than most developing countries. Only 2.4 percent of China’s GNP is spent on schools, compared to 6.7 percent in the U.S. and 7 percent in Taiwan. Even India, which has around a sixth of China’s GDP, spends more on education.

According to one survey, China ranked 99th out of 130 countries on per capita education spending. One mainland Chinese website admits that “the total number of illiterate people in China is still as high as 85 million, which is almost equal to the total population of Germany.”

From cultivation to corruption

After the CCP seized power, the motto of the prestigious Qinghua University in Beijing was reduced to “Self-Discipline and Social Commitment,” removing the words “Independent Spirit and Freedom of Conscience.”

Many have argued that China could better serve its people if it spent more money on true academic disciplines instead of having hundreds of Communist Party schools at all government levels. Statistically speaking, more graduates from these institutions have later been prosecuted for a variety of crimes than any other academic institutions in China.

As a popular Chinese joke about these Communist Party schools goes: “half of the students will arrest the other half in the future.”

The CCP’s Marxist-Leninist doctrine is officially atheist and rejects ancient Chinese beliefs in divine retribution and justice. From a young age, students are inculcated in the Party’s doctrine of class struggle, focusing their minds on power and profit as the traditional requirements of spiritual cultivation and cultural excellence were lost.

Edited by Leo Timm.