As our understanding of animal intelligence and capabilities grows, a growing number of scientists have begun to rethink the way animal cognition is assessed, resulting in compelling findings about unique animal capabilities that surpass human abilities.

Findings on animal intelligence have, in turn, influenced the way we perceive and treat different species. After surveying more than 1,000 Americans, the non-profit Faunalytics found that people are more willing to support the conservation of a species if they believe it to be intelligent, and less likely to feel empathy for small-bodied animals used for food.

Have we always valued animals based on how their abilities compared with ours? If we take a look at how our ancestors perceived and treated animals in the past, we may find a set of rational and moral criteria to guide us in assessing animals’ lives.

The status of animals in the ancient world

Ancient Greece

As the prevalent view in the West for nearly two thousand years, Aristotles’ position — which took rationality and moral equality as the main criteria — was the first to place animals far below humans in the categorization of beings. “Plants are created for the sake of animals,” he claimed, “and animals for the sake of men.” He believed that animals were irrational and had no interests of their own, which placed them in a different moral realm than humans.

One of his pupils dared to take a different opinion. Theophrastus, his successor in the Peripatetic school, argued that animals can reason, sense and feel just as humans do, and that killing them for food was unjust. But he was not the first to defend the life of animals in ancient Greece.

Influenced by the animist school, the prominent philosopher Pythagoras had already urged respect for animals, which, according to him, had the same kind of soul as humans. He believed that humans and non-humans were one spirit and that souls were reincarnated from human to animal and vice versa.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

This Greek thinker has been remembered through generations not only for his famous triangle theorem, but also for his spiritual insight and humane treatment of animals.

Early religions

In the East, respect for animals had already been advocated by the Jains in India. Being the first religious philosophy to promote total nonviolence toward animals of all forms, Jainism established “noninjury” or “non-harm” to any life as one of its fundamental principles.

As religions developed in the West, Judaism instructed people to show kindness and to respect animals, which, according to the Book of Genesis, were provided to humans to ‘Be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth and conquer it.” Thus, while killing animals for food was a common practice among Jews, inflicting unnecessary pain on animals was forbidden.

Although God had given humans dominion over animals, both beings were valuable and said to be — not have — a living soul. Since each of these souls was associated with the breath of life given by YHWH, respect for animals was a moral imperative. Man was expected to feed his animals before himself, and to alleviate suffering in animals.

An unexpected turn

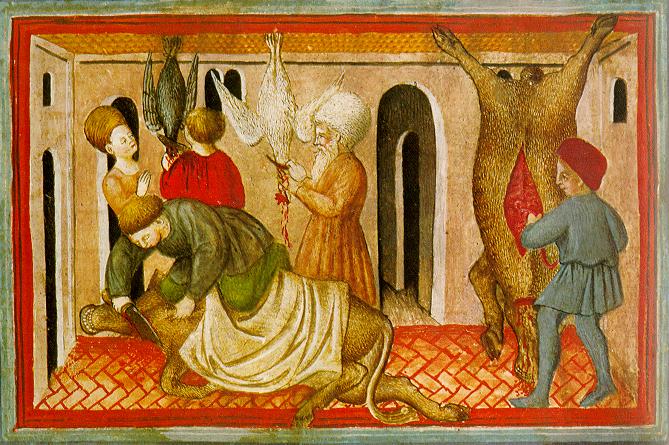

Compassion for animals experienced a significant downfall in Roman times, during which animals were often cooked alive to improve the flavor, and fierce fights between chained animals were an essential source of entertainment.

Historian W.E.H. Lecky, described the Roman games first held in 366 BCE, “Four hundred bears were killed in a single day under Caligula [12–41] … Under Nero [37–68], four hundred tigers fought with bulls and elephants…So intense was the craving for blood, that a prince was less unpopular if he neglected the distribution of corn than if he neglected the games.”

But even amidst the generalized cruelty, there were those who manifested their empathy for animals. The Roman philosopher Porphyry wrote two treatises on the subject, De Abstinentia (On Abstinence) and De Non Necandis ad Epulandum Animantibus (On the Impropriety of Killing Living Beings for Food), while Plutarch wrote some heartfelt lines in his manuscript On the Eating of Flesh:

“But for the sake of some little mouthful of flesh, we deprive a soul of the sun and light, and of that proportion of life and time it had been born into the world to enjoy. And then we fancy that the voices it utters and screams forth to us are nothing else but certain inarticulate sounds and noises…”

Eastern influence

As Western thought was being shaped by classical influences, the East saw the spread of Buddhism and its perception of animals as sentient beings. According to its teachings on rebirth and karmic retribution, human souls could be reborn as animals if they misbehaved, which entailed much more suffering compared to that of a human life.

By this logic, Buddhists believe that any given animal could have been their mother, sibling, child or friend in a past life; thus, we should treat them with the same moral standards as we do humans. By regarding all souls as part of the Supreme being, Buddhism teaches that animals are part of our universal family.

Animal intelligence influencing our perceptions

Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University, has been studying animals for years. In his book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?, de Waal describes cases in which animals exhibit surprising cognitive abilities.

“We hear that rats may regret their own decisions, that crows manufacture tools, that octopuses recognise human faces, and that special neurons allow monkeys to learn from each other’s mistakes,” he wrote.

Along with a better public understanding and appreciation of animals derived from these findings, numerous movements for animal rights have emerged, culminating in the idea of animal liberation, which advocates for an end to speciesism — the belief that humans possess moral rights unlike other species.

Some animal liberationists have employed moral shock as a method to raise awareness of animal suffering, with a number of activists resorting to property damage, animal releases, intimidation, and direct violence as a means to change society through force and fear. Others rely on nonviolent education and moral persuasion to promote veganism and the abolishment of animal agriculture.

Yet the question remains: “Where does one draw the line?” As de Waal told BBC, “I find it a very difficult topic to say that an elephant deserves certain rights or a chimpanzee deserves certain rights and a mouse doesn’t or a dog doesn’t.”

As many animal rights advocates have resorted to eating insects to avoid the killing of larger animals, the question arises as to whether all animals have moral standing. With fur coats having gone out of fashion and many conservationists targeting silk production next, we are left to wonder if such extreme postures will really do any good for humanity and our coexistence with the ecosystem.

Alternative views

According to Diana Rodgers, a nutritionist and sustainability advocate, opting for a lifestyle that excludes all forms of animal use may not be the solution. She explains that measures such as eliminating animal agriculture and adopting a plant-based diet are not the main issue. The matter revolves around the way animals are treated and the way natural cycles are maintained or disrupted.

Dr. Joel Kahn, a Detroit cardiologist, explained that the method of mass production is applied to animals by confining them in cramped enclosures and denying them normal social interaction. These conditions, according to Kahn, lead to aggression, which farmers usually control by sedating the animals.

“The problem is, we’ve really gotten pretty far away from what nature is,” said Rodgers. She explained that in a not-too-distant past, large herds lived in harmony with the environment, and that animals raised for meat enjoyed a lifestyle similar to that of their wild counterparts.

According to Rogers, raising meat may actually be good for the environment. “Animal poop is not waste, it’s actually fertilizer, and it can be quite valuable to the ecosystem,” she said. “We don’t see it that way today because we store it in manure lagoons and we’re overcrowding animals in factory farm settings.”

Returning to tradition

Rodgers refers to Mongolians as a good example of coexistence and dependence on animals: “Think of the Mongolians, they have grazing animals, not greenhouse tomatoes. They’re living on animals because that’s what does well on their land. And they’re pretty healthy, too.”

She explained that raising animals to provide nutritious foods has always been a traditional practice in many cultures around the world, just as meat, dairy, and eggs have been an integral component of their diets. The key, then, may be to return to traditional practices that respect the lives of animals and, at the same time, recognize their role in human survival. In this way, our harmonious coexistence with animals becomes possible.