Those looking for sustainable architecture are finding answers in tradition. China’s yaodongs, a form of ancient cave dwelling, has stood the test of time.

Unlike many ancient forms of accommodation and living, these buildings are still in use today and actually demonstrate high levels of efficiency, which can be valuable in our present search for energy alternatives.

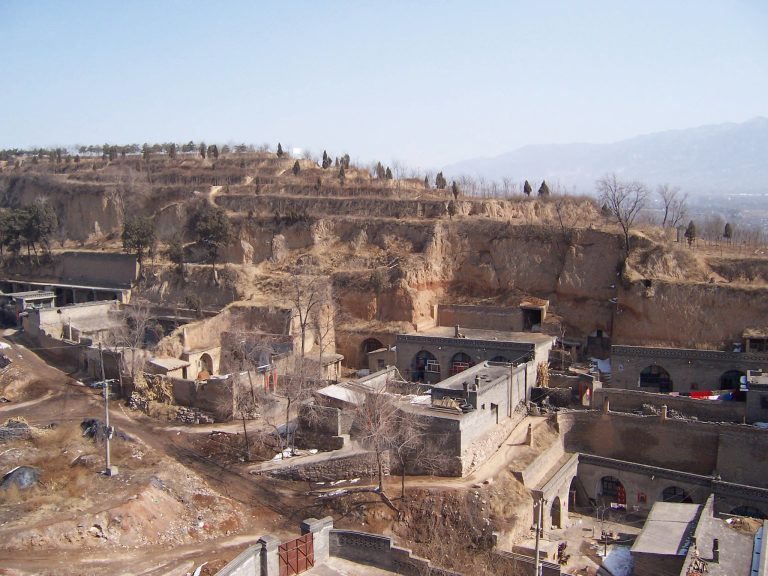

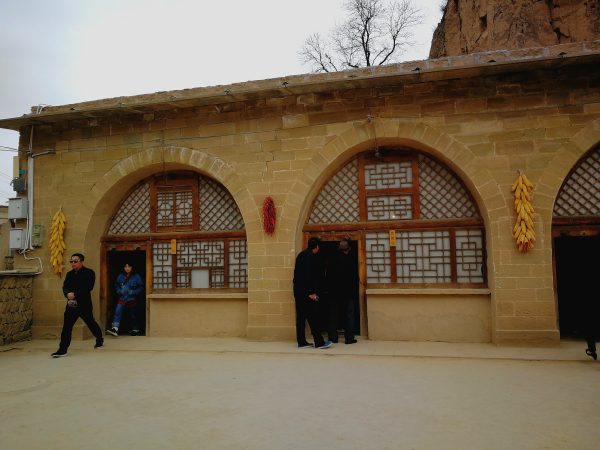

Yaodong, (窰洞) meaning “kiln caves,” were named for their arched interiors, designed much like the inside of a kiln. Many yaodongs are found in northwestern China, in provinces such as Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Henan — all of which are located in the Loess Plateau.

Depending on the topography of the areas where they are built, yaodongs can be constructed in three different ways.

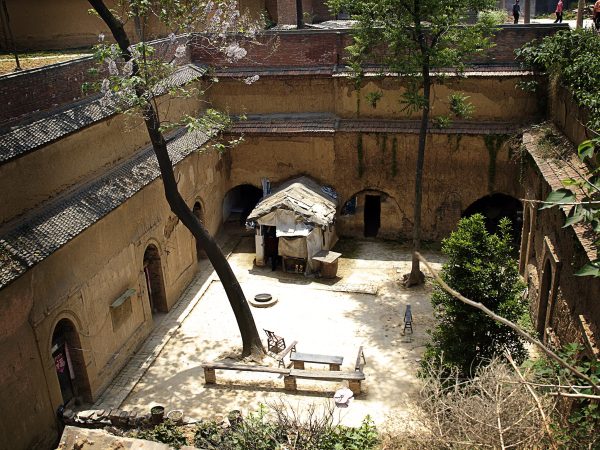

Yaodongs built on the slopes of hills, may have several stories, while yaodongs in flat areas are created by excavating rectangular wells about five to eight meters deep before reinforcing the walls of these wells, converting them into courtyards for the residents.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

There are also yaodongs that utilize stone or brick to construct the arched interiors, filling the empty spaces between and around each yaodong with soil to close them in.

It is believed that the first yaodongs were constructed during the Xia Dynasty (2100 B.C. –1600 B.C.). By the time of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.), yaodongs became more complex, with chimneys, kitchens and warm brick beds included in the catalog of each building. During the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties, the use of yaodongs spread throughout northern China.

Even today, yaodongs are still inhabited by the current generation, especially in the Loess Plateau. In fact, it is estimated that more than 40 million people still live in these dwellings — four times the population of Belgium!

“The cave topology is one of the earliest human architectural forms…there are caves in France, in Spain…people are still living in caves in India,” David Wang, an architecture professor at Washington State University in Spokane, said in a report by Los Angeles Times.

“What is unique to China is the ongoing history it has had over two millenniums,” he added.

How do these ancient buildings continue to have staying power in an era where modernization dominates our daily lives?

The reliability of the yaodong may be due to its efficient and thrifty design. The construction requires only the local loess soil. This soil that gave the Loess Plateau its name is far more plentiful than wood or stone. The thick soil walls insulate heat well, keeping the buildings cool during the summer and warm during the winter.

The brick beds, known as kang (炕), offer a clever way to warm the rooms and their occupants. The bed serves as a funnel to connect the stove in an adjacent room to the chimney. The hollow kang allows the heat and smoke to flow from the stove to the chimney, making efficient use of a warm byproduct to heat the bed.

As researchers delved into the art of the yaodong, the dwellings have been highly appraised for their sustainable architecture, following a traditional Chinese concept; one that transcends the yaodong itself — the harmonious relationship between man and nature.

Yaodongs do have a striking drawback, however. They are not immune to natural disasters. In 1556 A.D, the Shaanxi earthquake — regarded as the deadliest in history — hit Shaanxi Province and killed as many as 830,000 people. It is said that, because loess is highly susceptible to erosion, the quake devastated the caves and thus took many lives with them.

With its benefits and flaws, the yaodongs’ unique architecture and role in Chinese culture and history continue to fascinate researchers. The design and benefits of such housing could help reduce energy consumption and promote a traditional lifestyle.