It was the third day of the third lunar month of the year 353. Wang Xizhi, the greatest calligrapher in Chinese history, had invited a group of family and friends to his Orchid Pavilion in celebration of the annual Spring Purification Festival — an occasion to welcome the long-awaited warmth of spring.

Numerous scholars had gathered at the picturesque spot near the water to drink and play.

The scene was surrounded by imposing mountains that, along with pristine bamboo trees on all sides of the harmonious pavilion, were witnessing the solemn celebration.

A refreshing breeze was drifting through the air, like remnants of the winter vapors that had been replaced by the sun rays of the new season. And accompanied by the humble tones of a subtle melody, the guests settled themselves by the banks of the river, where some of the noblest verses of Chinese poetry were about to spring.

A poetic drinking game

The scholars began to play an artistically challenging drinking game. Servants filled small cups with wine to place them on the water stream on top of large leaves. If one of these cups floated towards a scholar, he would have to either provide a suitable verse, or take a drink.

READ ALSO:

- Su Shi, the Ancient Poet Who Put the People First

- The Past–And Present–of China’s Imperial Exams

- Gongshi: The ‘Scholar’s Rocks’ of China

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Amidst modest laughter, illustrious conversation, and a bit of tipsiness, a total of 37 poems were composed that afternoon. So idyllic was the setting and so convivial the occasion, that Wang Xizhi felt inspired to write a preface to the anthology of the guests‘ collected poems.

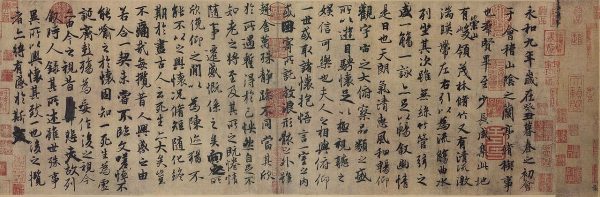

Utilizing a weasel whisker brush on cocoon paper, Wang made use of his unparalleled calligraphic skills to render the verses that sprang from his soul. The opening piece of writing, so harmonious to the eyes and uplifting to the spirit that it became one of the most famous works of Chinese calligraphy — the “Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion” (Lántíngjí Xù 蘭亭集序), or simply the “Orchid Pavilion Preface.”

Apart from being a drinking party to outwit each other’s talents, the gathering at the Orchid Pavilion was a general celebration of scholarly reflection. As for the poetic game, its role in the creation of the famous verses earned it its own place in Chinese folk traditions, becoming the popular form of entertainment known as the “Winding stream party” ( liúshāngqūshuǐ 流觴曲水).

Scholar’s music: The humble yet expressive gu qin

Known as “the father of music,” the gu qin (古琴) is an ancient seven-stringed zither that has been favored as the instrument of the sages because of its great subtlety and refinement.

In ancient China, its slow, deep tones used to grace most academic gatherings, creating a contemplative atmosphere well-suited for reflection. Naturally, the humble sounds of the gu qin also accompanied the poetic reunion at the Orchid Pavilion.

The origin of the gu qin dates back to early Chinese history, when it is said gods and mortals coexisted on the land. The story goes that Fu Xi (伏羲) a demigod who had been appointed Celestial Ruler of the East, was one day pondering how to help the people of the human world.

When he saw them struggling for food, he invented weapons and fishnets so that humans could hunt. When he saw them falling ill from eating raw meat, he taught them the secrets of making fire. He later created marriage to bond men and women in sacred union and developed a system of divination.

However, Fu Xi wanted to give them even more happiness, so he created music. What he may not have known was that the musical culture he was about to create would survive for over five millennia.

Fu Xi’s first zither-like instrument was made from the wood of a blessed tree. It had five strings representing the five elements, and twelve frets corresponding to the months of the year. One end was four inches wide, symbolizing the four seasons, and its two-inch thickness alluded to the dual forces of yin and yang.

As one of the most revered instruments in Chinese history, the gu qin reminds us of what it meant to be an intellectual in ancient China: to be as humble as the silent zither but as insightful as its most expressive tones.

Spellbinding calligraphy

Now let’s explore what happened with Wang’s masterpiece, the Lántíngjí Xù (蘭亭集序). The memorable Orchid Pavilion gathering took place during the Jin Dynasty (266-420), at a time in which imitation was the highest form of flattery.

Most of Wang’s calligraphic works were copied in ink on papers or carved on stones to be preserved through the ages, but very little of his original work exists at present. The famous preface was not spared this unfortunate fate, as only its reproductions survived to this day.

According to historical records, the original masterpiece was passed down in the Wang family for generations until its last heir — a monk called Zhiyong — passed it on to his disciple Biancai, in an attempt to keep the manuscript in virtuous hands.

Eventually, the designs of fate brought the renowned poem to Emperor Tang Taizong of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), who had only seen copies of the original and knew the value of the matchless brushstrokes. Legend has it that the emperor took the original with him to the tomb.

Fortunately, the numerous copies available to us today provide an invaluable opportunity to glimpse the handwriting of China’s “Sage of Calligraphy”, who through timeless verses and heartfelt words conveys the transience of the joys and sorrows of human life, which is, at the same time, but a blink of history’s eyes.

If you want to get a sense of the contemplative atmosphere at the Orchid Pavilion, check out this masterpiece by the Shen Yun Symphony Orchestra depicting the timeless scene through music.