Do you have a favorite cotton T-shirt, love the crisp feel of fresh cotton sheets, or appreciate the absorptive power of cotton towels? You’re not alone. Cotton is the most widely-used natural fiber, and one the most important non-food crops around the world.

About 80 percent of the world’s natural fibers come from the cotton plant (genus Gossypium), a member of the mallow (malvaceae) family — which includes the ever-popular cacao tree (chocolate), and the weird but wonderful okra.

Continuing our series on natural fibers, we enter the plant kingdom for a look at the process — from seed to spinning — of cotton, an industry that provides income for some 250 million people worldwide. If you are unaware of how much work goes into the production of cotton, prepare to be enlightened. You may never look at a cotton ball in the same way again!

The cotton plant

The genus Gossypium first appeared over 5 million years ago, with different species of cotton being domesticated independently between 6,000 and 7,000 years ago in various subtropical regions. In its native lands, cotton grows as a perennial shrub or tree. Four main species continue to be grown throughout the world today, mainly treated as annual plants for economical purposes.

G. hirsutum, first cultivated in Mexico, is the most commonly grown cotton species today. It produces medium staple fibers used in a wide variety of textiles. G. Barbadense (Pima Cotton), first cultivated in Peru, has long, strong fiber used to produce high-quality yarns, fine fabrics and hosiery. G. arboreum is an Old World cotton native to India. It has short, weak fibers that are mainly used for stuffing, carpeting, and coarse, inexpensive fabrics.

Growing cotton

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Cotton seed takes about two weeks of warm temperatures (70-80 degrees Fahrenheit) to germinate. The plant will grow in a variety of soils, but needs full sun and a long, frost-free growing season (four to five months) to mature. With quality seed, adequate moisture, and some help from nature, farmers may get a good “stand” containing two to four plants per foot in each row.

In the United States, cotton is only grown commercially in the southern and western states, yet the U.S. is still one of the top three cotton-producing countries in the world, alongside China and India.

Between 60 and 80 days after planting, cotton produces beautiful flowers like its cousins hollyhocks and hibiscus, changing from a shade of white to a shade of pink as they open up. The flowers are self-pollinating, but temperatures above 100 and rain will both reduce pollination, which can only happen on the first day of opening.

Successful fertilization of one flower will produce about 30 to 40 seeds. As the seeds develop, they grow the precious cotton fibers on their seed coat, numbering between 10,000 and 20,000 per seed. A ripe seed pod will split open naturally after about four months, revealing the fibrous “boll,” (pronounced “bowl”) ready for picking.

Harvesting cotton

While plucking cotton may appear to be a pleasant experience, the open, desiccated seed pod has sharp and prickly edges, so careful fingers or protective gloves are wanted for hand-picking. This method produces the cleanest, best quality cotton, as each boll is harvested at its peak, without any other plant debris. Although mechanical harvesting techniques are available and used widely in the US, India and China still rely on manual labor to harvest their cotton.

Commercial cotton pickers can pick about 1,000 times as fast as a person. They cost between $90,000 and $900,000, so only relatively large-scale producers invest in this machinery. With mechanical harvesting, chemical defoliants — dubbed “harvest aids” — are often employed to kill the plants to minimize the amount of leaves collected with the bolls.

Processing cotton

Whether hand- or machine-harvested, cotton then goes through many steps of processing, beginning with the fibers being separated from the seed.

Ginning

Cotton seeds are covered with two kinds of fibers. The longer fibers are called “lint,” and are suitable for textiles. Shorter fibers, called “linters,” or “fuzz” are used in other products like paper, quilt batting, and padding for cushions.

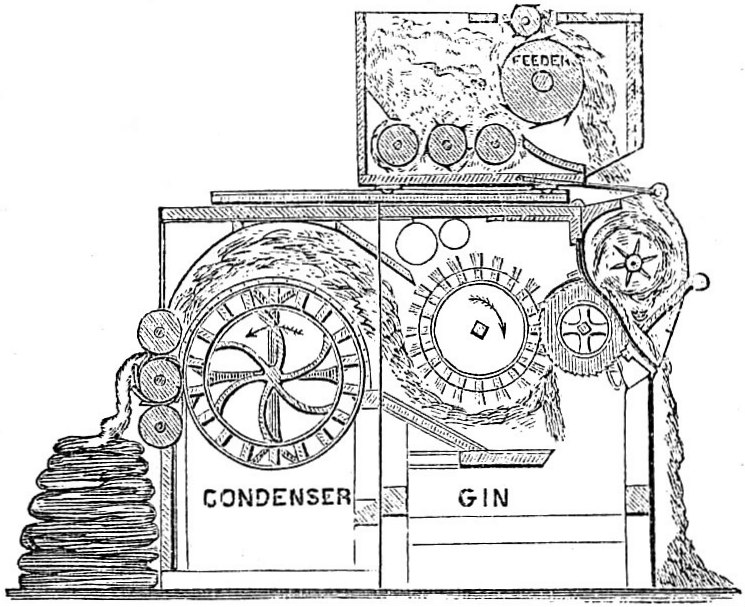

Traditionally, all cotton was cleaned by hand, with an able person being capable of processing around five pounds of fiber per day. In 1793, American inventor Eli Whitney introduced the cotton gin, short for “cotton engine,” which so efficiently removed the fibers from the seed that it revolutionized the cotton industry.

In a cotton gin, the bolls loosened with air, and passed through a series of rotating, spiked cylinders and brushes to remove the seeds (about two thirds the weight of uncleaned cotton) and collect the fibers.

Manual cleaning can be accomplished by one of two methods. The seeds are teased out by pulling the fibers away with the fingers; or a small dowel can be rolled against the boll to press the seed out.

The seeds do not go to waste. Some are planted for next year’s crop, but most cotton seeds become important by-products — like vegetable oils and high-protein animal feed.

Additional cleaning

Once the seeds are removed, commercial cotton may undergo various additional cleaning processes — including mechanical cleansing to remove any non-lint contaminants, scouring with detergent to remove natural waxes that inhibit absorption, and purification (bleaching) to remove all color — before the cotton can be prepared for carding.

Batt formation and carding

Carding is the process by which the fibers are lined up parallel to one another so they can be spun into yarn. Before carding, the fibers must first be loosened, in a process called batt formation. Machine batt formers open up the fiber to form a continuous, evenly-matted structure (batt), but this can also be done by teasing the cotton out by hand, similar to wool. This ensures weight consistency in the carding, ultimately leading to an evenly spun product.

Carding is traditionally done by hand, while commercial carding is done with a machine — where a series of toothed, wire-wound cylinders separate and transport small amounts of fiber across wire-covered “flats,” aligning and straightening the fibers.

Modern cotton producers often combine many processes — including opening, carding, drawing, roving and spinning — into one machine.

Hand carding is done with a pair of fine combs that look very much like pet brushes. Gently pulling the empty brush against the cotton-loaded brush not only straightens the fibers, but also filters out any impurities that were not removed with the seeds. After a few strokes, the cotton is transferred to the other brush, combed again, and rolled into a loose cylinder, called a “roving” ready for spinning.

Extra-fine cotton may undergo an additional “combing” to remove short fibers for a softer, silky-feeling product.

Spinning

Finally, the fibers are spun into thin threads to be weaved or knitted into fabric, or further spun into yarn. Traditionally, spinning wheels and spindle whorls were used to accomplish this task, but now it is mainly done on large and efficient spinning machines.

With a spinning wheel, the rotation necessary to spin the fibers comes from a foot treadle, while a spindle whorl is a hand-held device twisted with the fingers. In any case, a small amount of fiber is continuously fed into the device, which twists the fibers, while maintaining tension for a strong and even thread. The finished thread is loaded onto a bobbin, ready for use.

Cotton and chemicals

Cotton plants have a hard time competing with weeds, and are plagued by many insect pests and diseases, including the notorious “boll weevil” — an insect so destructive that many states illegalized the cultivation of cotton just to prevent its spread.

Growing cotton against these odds is either very labor-intensive, or heavily dependent on chemicals — or both. In addition, chemical defoliants — one of the most toxic farm chemicals on the market — are commonly employed to improve efficiency of harvest.

In the year 2000, the U.S. Department of Agriculture recorded 84 million pounds of pesticides and 2 billion pounds of fertilizers applied to the nation’s 14.4 million acres of cotton. The effects of these chemicals go far beyond the targeted pests — with toxins entering the ecosystem, harming cotton workers, and lingering in the final product.

Does this mean we should forego our favorite fabric and start wearing recycled plastic? The beauty and benefits of cotton are so numerous that it’s worth looking a little deeper than this superficial solution.

With greater environmental awareness, the use of chemicals is slowly subsiding. A growing number of growers are willing to put forth the extra effort to go organic, and some companies boast TCF (totally chlorine free) in their purifying process.

Traditional methods still work to produce quality material, they just don’t produce the same quantity. Perhaps we should consider simplifying our wardrobe somewhat to include fewer, more-conscientiously-created articles of clothing.

Choosing organically-grown cotton — or growing your own — can help reduce the amount of harmful chemicals in the environment, and in your closet; so your conscience can rest easy, and your body, comfortably.