In Chinese history, four beauties stand out not only for their exquisite appearance, but also for the significant role they played in the fate of their respective dynasties. Although their physical appearance was remarkable in itself, the way they shaped history was dependent on their character. An upright and selfless heart has always been considered priceless and eternal; and as we shall see, it has the power to make or break an empire.

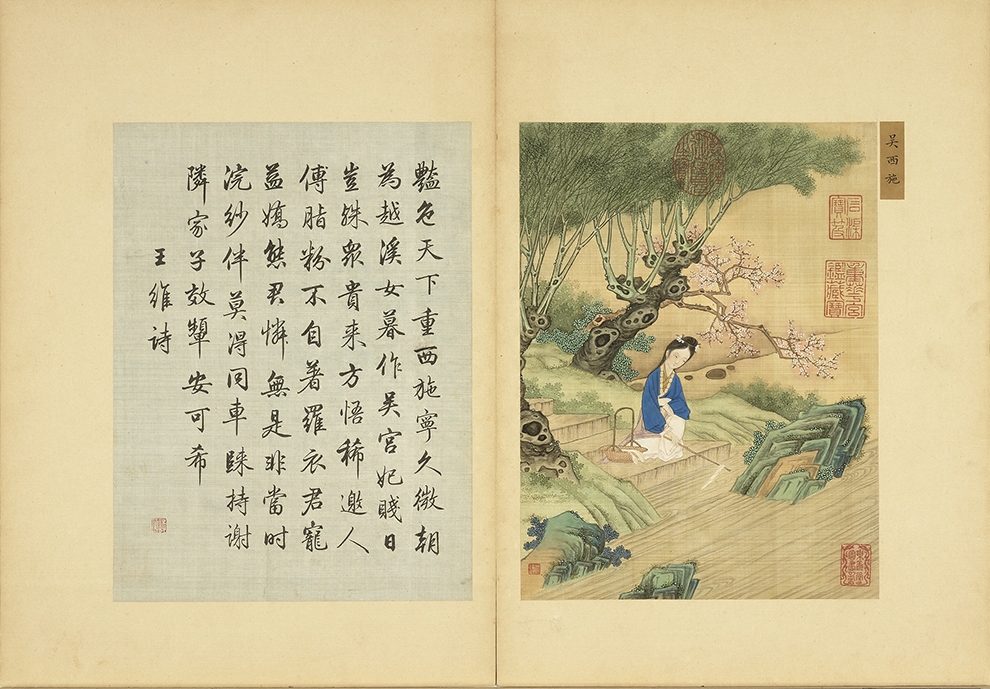

Xi Shi, whose unearthly beauty made fish sink

According to Chinese folklore, Xi Shi was so beautiful that when she looked down into a pond, the fish forgot how to swim and sank back into the water. Her beauty is described with a well-known expression:

西施沉魚 (xī shī chén yú)

“Xi Shi [makes] fish sink”

Xi Shi was born in a small village during the Spring and Autumn Period, a turbulent time in Chinese history of divided kingdoms and frequent wars. The state of Yue, where she lived, had been conquered by Fuchai, king of the state of Wu.

To regain independence, Goujian, the original king of Yue, and his loyal advisors hatched a plan to defeat Fuchai: Introduce him to a young beauty whose grace and talent were sufficiently enchanting as to weaken the king’s defenses. The selfless Xi Shi accepted the important task and began to study etiquette, singing and dance. After three years, she was presented to King Fuchai, who was instantly spellbound by her captivating beauty and refined character.

Over the next 20 years, Fuchai focused his attention increasingly on Xi Shi. As expected, Military affairs were neglected, and Goujian was able to defeat Fuchai, restoring independence to the state of Yue. To this day, Xi Shi’s selflessness and courage are an enduring model for honor and loyalty.

Wang Zhaojun, whose pure loveliness caused birds to forget how to fly

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The second beauty was born in 50 B.C. to an aristocratic family. From an early age, Wang Zhaojun was well-versed in the Chinese classics and adept in the Four Arts of a scholar – qin (琴, playing a seven-string Chinese zither), qi (棋, the strategy game of Go), shu (書, Chinese calligraphy) and hua (畫, Chinese painting). She was especially known for producing moving melodies on the pipa – the Chinese lute.

When Zhaojun came of age, her beauty blossomed and her demeanor was perfected. Her charm and talent made her renowned throughout the land. It was no surprise that, when Emperor Yuan requested that one lady from each district enter the inner palace, Zhaojun was selected to represent hers.

Traditionally, when choosing a new concubine, the emperor did not see the ladies in person, but based his choice on portraits depicting each lady in the harem. Unfortunately, the painters of the time were greedy and did not mind beautifying a lady in exchange for a generous tip.

Since the virtuous Zhaojun was above bribery, her image — as presented to the emperor — was far from flattering. Thus, for years, she lived in the royal palace without ever being chosen to keep him company.

This was during a period of tensions between the prosperous Han Dynasty and the nomadic groups of the north. Many emperors found it difficult to maintain peace; but finally, a unique opportunity arose.

Wishing to strengthen the then-peaceful relations, Xiongnu, the leader of the nomadic tribes, came to pay tribute to the emperor. Although the emperor gave him abundant rewards in return, Xiongnu wanted more. He wished to make a Han princess the queen of his tribe.

The emperor knew that making Xiongnu an imperial son-in-law would ensure lasting peace on the frontier; but sending his daughter to live with the nomads was a heartbreaking thought. Not wishing to miss this extraordinary opportunity for peace, the emperor consulted his loyal advisors. Together, they determined that another maiden from the palace should be bestowed with the title of “princess” and take his daughter’s place.

Zhaojun was approached with the proposal. Leaving a pampered existence in the palace for a nomadic life — tending livestock on desolate land with no opportunities to see her family — could not have been an easy decision to make. She understood the significance of this weighty responsibility, however, and set aside her own concerns.

On the day of her departure, the emperor checked to see that everything was going according to plan. Mesmerized upon finally catching sight of Zhaojun, he realized with sorrow that he was losing not only a refined beauty, but one of remarkable character and grace.

With tears in her eyes and determination in her heart, Zhaojun climbed onto a horse and departed with the nomads. As her beloved homeland disappeared into the horizon, she unpacked her pipa. Many artists have depicted the touching scene of a heavenly beauty playing heartfelt melodies on her way to the northern frontier, inspiring another Chinese expression:

昭君落雁 (zhāo jūn luò yàn)

“Zhaojun [makes] birds drop.”

Zhaojun was a virtuous queen, and a great asset in keeping peace — which lasted a remarkable 60 years. Zhaojun’s contribution is often considered as important as that of many famous Han generals.

Diao Chan, whose captivating charm eclipsed the moon

Our third beauty appeared at the end of the Han dynasty, when the incumbent emperor passed away and his young son was placed on the throne. Taking advantage of the boy’s weakness and inexperience, a cold-blooded tyrant named Dong Zhuo took over the imperial palace, and planned to appoint himself the new leader of the empire.

Dong Zhuo’s right-hand man was his adopted son Lü Bu, an invincible warrior of ruthless character. Lü Bu had already disposed of his previous patron, and served Dong Zhuo mainly out of self-interest. Nevertheless, he was an effective strong-arm for the tyrant.

The cruelty of Dong Zhuo was beyond description. In the hands of a man who killed and tortured for pleasure, the future of the whole empire looked bleak indeed.

Troubled by the lamentable state of his nation, Wang Yun, a loyal minister, was contemplating how to get rid of the dictator. One night, taking a stroll in search of inspiration, Wan Yun caught a glimpse of his adopted daughter looking at the moon. Her beauty was so captivating that even the moon, in embarrassment, covered its face behind the clouds.

貂蟬閉月 (diāo chán bì yuè)

“Diao Chan eclipses the moon.”

Suddenly, Wang Yun realized that Diao Chan’s beauty could save the empire. In desperation, he knelt before his beloved daughter and asked if she was willing to help restore peace to the nation.

Surprised and troubled to see her father on his knees, the 16-year-old girl gently prompted him to get up and assured him that she would do anything to repay all his kindness. Although the plan he revealed was quite shocking, she steadied her heart and accepted the mission: a virtuous deed that would mean the loss of her maidenly virtue.

Wan Yun organized two separate banquets for Lü Bu and Dong Zhuo. When Diao Chan made her appearance at each lavish affair, the guest of honor was readily enamored by the charming girl. To incite jealousy, Wan Yun offered his daughter’s hand in marriage — first to Lü Bu, and then also to Dong Zhuo. The latter did not wait for the wedding ceremony, but took her to his residence that same evening.

In the following days, Lü Bu could not help noticing his promised lady’s absence at the minister’s mansion, and was devastated to learn that the tyrant had taken Diao Chan for himself. A strategic wedge was driven between the dangerous duo, and the athletic warrior ultimately killed the vicious Dong Zhuo. Lü Bu was executed for murder, and order was restored within the Imperial Palace.

Wan Yun bowed to his daughter for saving the empire. Her legacy is a timeless embodiment of a highly praised quality in traditional Chinese culture known as “yi” (義), which includes righteousness, honor, benevolence, loyalty, selflessness and justice.

Yang Guifei, whose stunning appearance put flowers to shame

Our last beauty did not save the empire, but instead, brought it to its knees. Her exquisite appearance proved to be all-consuming for the emperor — a regrettable attachment for everyone involved.

In the early 8th century, the Tang dynasty was at its peak. Emperor Tang Xuanzong had just lost his closest concubine, and Lady Yang came into his favor. It was said that Lady Yang was so beautiful that flowers, at her sight, hid away in shame.

貴妃羞花 (guì fēi xiū huā)

“Guifei shames the flowers.”

As if under a spell, the emperor spent his days showering her with jewels and the finest gifts, and indulged in exquisite meals and entertainment by her side. He also bestowed titles and honors on her and her relatives, doing everything possible to please his enchanting mistress.

But as the emperor increasingly neglected state affairs, unrest boiled on the frontier, where troops prepared to seize the capital. Imperial advisors complained numerous times that Lady Yang was distracting the emperor, but he refused to listen.

In barely a year, the rebel army made its way to the Tang capital of Chang’an, forcing the emperor and his men to flee to the mountains. Of course, the emperor brought his lovely lady with them.

Exhausted and disgusted, the emperor’s entourage finally demanded the elimination of the cause of the empire’s decline: Lady Yang. The emperor could hardly contemplate a life without his precious consort; yet seeing no other options in this grave situation, he mournfully consented.

As a sacrifice for the empire, Lady Yang was forced to take her own life. Her body was buried beside a rugged road, wrapped in fine purple silks and masses of fragrance.

The emperor was restored to power, but his heart remained with his lost love. He handed the throne to his son, commissioned a painter to create a fine portrait of Lady Yang, and fed his perpetual distraction in a secondary palace.

A meaningful idiom

Inspired by these four ladies, otherworldly beauty is still described today with the idiom “沉魚落雁,閉月羞花,” which implies that a lady is so beautiful that she causes fish to sink, birds to fall, the moon to hide and flowers to be ashamed.

As the Four Beauties have demonstrated, magnificent beauty can carry tremendous power, and it is best coupled with virtue and responsibility.