Hong Kong saw as many as a million people march on New Year’s Day 2020, chanting pro-democracy slogans as they crowded the streets that afternoon.

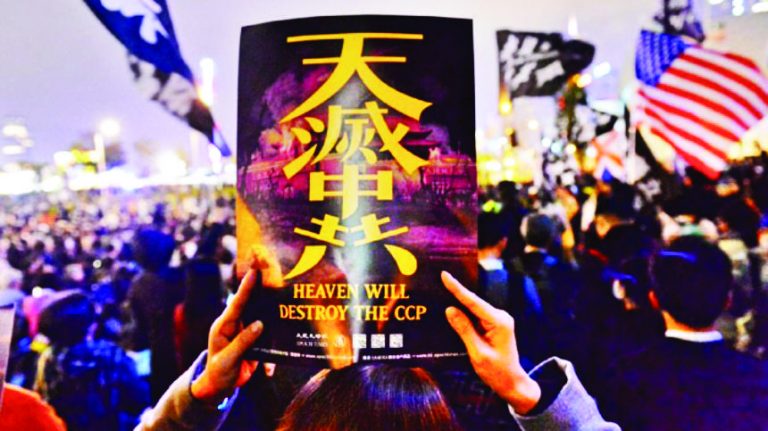

Marchers held signs and flags emblazoned with protest slogans, such as the ubiquitous “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times,” “Five demands, not one less,” and “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party.”

The event was organized by the city’s Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF) and given a letter of no objection by the Hong Kong police. Protesters rallied in Victoria Park on Hong Kong Island before beginning the march at around 2:40 p.m. local time to Charter Road in Central, about a mile west.

Earlier in the day, Hongkongers who gathered along Victoria Harbor and other central locations counted down to the new decade, chanting slogans while flooding the scene with blue light from their phones.

CHRF had planned the events to demonstrate that they and millions of other Hongkongers would continue to oppose what they see as the Communist Party’s steady encroachment on the former British colony’s rights under the “one country, two systems” arrangement.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

“On New Year’s Day, we need to show our solidarity … to resist the government. We hope Hong Kong people will come onto the streets for Hong Kong’s future,” Jimmy Sham, a leader of the Civil Human Rights Front, said. The theme for the events was “Persist in 2020.”

According to CHRF, 1.03 million people took part in the event. Police claimed that only around 60,000 were in attendance.

1.03 million people attended the rally, according to the Civil Human Rights Front. (Image: The Epoch Times)

The New Year rally and march were planned to last until 10 p.m., but was cut short following a clash between a small group of protesters and police officers. The latter fired tear gas and pepper spray, and arrested five “rioters” for vandalizing a bank.

Police contacted the event organizers and ordered them to end the protest at 6:15 p.m.

The Hong Kong protests began in the spring of 2019 in response to a now-withdrawn bill that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China, where courts are controlled by the Communist Party.

The proper beginning of the anti-extradition movement, however, is generally regarded as June 9, when over 1 million people filled the streets to demand the bill’s withdrawal. Throughout the summer, the protests evolved to become a broad pro-democracy movement, with five major demands, including universal suffrage.

‘Five demands, not one less’

The events of 2019 represented the culmination of pent-up anger among the Hong Kong populace at a trend toward ever-greater interference in their city’s affairs by the mainland communist Chinese government.

Apart from the withdrawal of the extradition bill, the Hong Kong protesters have been demanding the removal of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam, an independent investigation into police violence, the release of the more than 6,000 protesters arrested since the beginning of the demonstrations, and for the government to stop calling the protesters “rioters.” The program is collectively known as the “five demands.”

Passing the extradition law was an issue of prestige for Carrie Lam and the Chinese Communist Party. (Image: wikimedia / CC0 1.0)

According to a recent poll conducted by Reuters, 59 percent of Hongkongers support the major protest goals. And in the citywide local elections held in November, pan-democratic candidates received over 80 percent of the votes in a landslide victory that was said to have shocked Beijing.

Communist Party-controlled media portray the Hong Kong protesters as violent thugs manipulated by hostile foreign forces whose aim is to separate Hong Kong from China.

According to the Reuters poll, however, only 17 percent of more than 1,000 respondents said they favored Hong Kong independence, and 80 percent said they supported the “one country, two systems” arrangement.

Most respondents said that the administration of Carrie Lam, who was chosen with Beijing’s approval, was responsible for the turmoil and sporadic violence that overtook the city.

Echoes of Beijing and Berlin

Many have compared the Hong Kong protests to the massive demonstrations in East Germany that, in 1989, led to the dismantling of the Berlin Wall and the end of communism in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe.

While protests over corruption and economic injustice are common in mainland China, the spread of pro-democracy sentiment could be a regime-ending proposition for the CCP.

In November and December, protest slogans used in Hong Kong were adapted by demonstrators in the nearby city of Maoming, Guangdong Province. Thousands of people threw Molotov cocktails and overturned police cars to express their opposition to a controversial crematorium project.

Contrary to the Communist Party’s insistence that the demonstrations are a separatist movement, the Hong Kong protesters and the general public tend to view their resistance as continuing the legacy of the 1989 Tiananmen protests, and as a fight against dictatorship.

A comic-style artwork spread on social media shows a female protester wearing a hard hat and carrying a yellow umbrella — common items used as protective gear by demonstrators — holding up a hand to a reflective pane of glass showing a scene from Tiananmen Square in Beijing 30 years earlier. A Chinese protester mirrors her stance; behind her is a banner written in simplified Chinese characters with the line “Give me liberty or give me death.”

A piece of artwork by a supporter of democracy in Hong Kong linking the anti-extradition bill protests to the pro-democracy movement in Beijing in 1989. (Image: via Reddit)

The 1989 protests in China ended with the deployment of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army in Beijing and the shooting of thousands of students at Tiananmen Square and in the surrounding district. But so far, the Chinese and Hong Kong authorities have avoided overt bloodshed.

Mainland Chinese authorities have taken an outwardly hands-off approach to the unrest, preferring to let the local police handle the protesters. But Beijing has signaled that military force is not off the table, and is finding roundabout ways to escalate the repression.

In August, PLA units deployed to Shenzhen, the city across the border from Hong Kong. In November, members of an elite PLA special forces team were deployed to help clear debris from the streets.

There have also been reports that Hong Kong protesters are being detained in mainland China, despite the withdrawal of the extradition bill this October. Video posted to social media shows police loading captured protesters onto trains that may have been bound for Shenzhen. Simon Cheng Man-kit, a Hong Kong businessman who was detained while on a day trip to Shenzhen, says he heard police berating people who may have been protesters in the jail where he was being held.

Follow us on Twitter or subscribe to our newsletter