One of the three most well-known empresses in the history of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) was Empress Fuca or Empress Xiaoxianchun (孝賢純皇后, 1712—1748). Although she lacked the political achievements of Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang (孝莊皇太后1633–1688) or the sheer ambition of Empress Dowager Cixi (慈禧太后, 1835-1908), during her short life, she was regarded as almost a perfect monarch’s wife and was recognized as the most virtuous empress of the Qing Dynasty.

The empress was born into a noble family — the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner (镶黄旗) Fuca clan. The Bordered Yellow Banner was the leading banner led by the emperor himself and enjoyed a very high status. Lady Fuca’s father was a first-class duke and his father had been a Minister of Revenue. Her uncle was a court official. Despite her noble upbringing, she was said to have possessed an unassuming nature, always maintaining elegance and dignity.

When she was nine, Lady Fuca’s family received a sudden visit from Prince Yinzhen who discovered a script she had written in the style of the great Chinese calligrapher, Liu Gongquan. Impressed, the Prince asked Lady Fuca to demonstrate her talents in person, so she wrote one of Emperor Kangxi’s poems for him.

According to the custom in the Qing dynasty, emperors were addressed by the name given to their reign, rather than their given name. Prince Yinzhen, who would later be enthroned as the Emperor Yongzheng (雍正帝), asked the young Lady Fuca to explain the meaning of the poem. She responded, “China’s Great Wall may be strong and formidable, but without a benevolent and virtuous administration [in place], it could not stop the takeover by the Manchu heroes.”

Prince Yinzhen brought back Lady Fuca’s calligraphy and showed it to three of his sons, saying, “This was written by a nine-year-old girl. If you do not have the heart to work hard and improve yourself, you might turn out to be inferior to a girl.”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

After being enthroned as Emperor Yongzheng, he was delighted to arrange the marriage between Lady Fuca and his fourth son, Hongli. Prince Hongli was later enthroned as Emperor Qianlong (乾隆帝), making Lady Fuca an Empress. Emperor Qianlong (乾隆帝) had the longest reign, 63 years, and the highest life expectancy, 89 years old, in Chinese history.

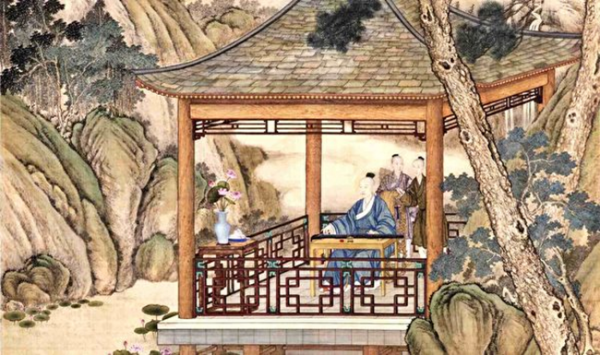

The royal couple were said to share many mutual interests. They would often recite poems, paint and play musical instruments together. She would sit for hours listening to her Emperor, share his joys and sorrows and assist him in resolving his troubles; when the rain and snow came, they celebrated together. Empress Fuca took great care of Emperor Qianlong. When he fell ill, she would not leave his side until he had fully recovered.

The Empress lived a life of frugality, followed tradition and was described as kind, level headed and modest. While many within her circle wore jeweled hair pins made of gold, silver or pearls, she wore simple flowers.

On one occasion, Emperor Qianlong told her a story detailing the struggles of his Manchu ancestors, who used deer hide for their pouches because they were too poor to afford cloth. Upon hearing the story, the Empress immediately got to work sewing a pouch of deer hide.

When she presented her work to her Emperor, he was deeply touched. He always carried the gift with him, saying that it reminded him of his ancestors, and, more importantly, of the love between him and his Empress.

It is said that Emperor Qianlong had as many as 3,000 consorts, yet his favorite was the virtuous Empress Fuca.

The Empress took her duties seriously

Filial piety was held in high regard by Emperor Qianlong, and the Empress treated the Mother Dowager, her mother-in-law, with respect and kindness, as if she were her own mother.

The Empress approached each of her duties with care and earnestness. While she was regarded as the head of the women’s quarters in the palace, she did not use her authority and politics to supervise the other consorts. Instead, she was courteous, caring and above all else, fair. With this disposition she gained the trust and respect of her servants and the Emperor’s consorts.

Legends say that the wife of the Yellow Emperor (黃帝), Luozu (螺祖), was the first empress ever to teach her people how to plant mulberry trees and cultivate silkworms to produce silk. She was given the honorable title of “The Ancestor of Silkworms (嫘祖始蠶).” As far back as the Zhou Dynasty, the Chinese people have performed rituals to pay respect to the Ancestor of Silkworms for teaching the people the art of silk making.

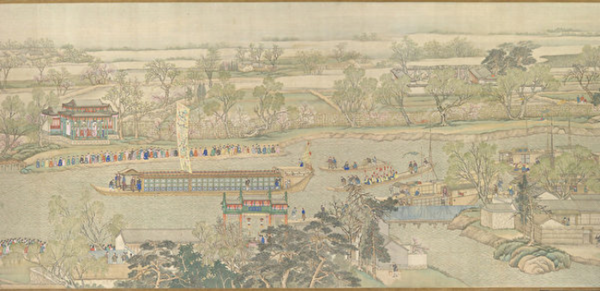

Empress Fuca was the first empress ever to perform the ritual during the Qing Dynasty, which she did with the emperor’s other consorts. The ceremony was commemorated in 1751, when artists painted depictions of the ceremony on four scrolls in memory of the Empress.

The ceremony would be performed every third lunar month of the year. When there was an abundance of silk, the Empress would dye and weave the silk into fine clothing for her Emperor. Emperor Qianlong greatly enjoyed wearing the silk clothing his Empress weaved for him and wore the clothing while worshiping, attending court or on other business.

The Empress bore four children for her Emperor, but three of them tragically passed away at a young age. Over time, her grieving eroded her health. During a boat tour to the eastern province of Shandong, the Empress watched the carefree fish swimming in the river. She sighed wistfully and said, “As I am not a fish; I would not know how happy the fish is.” On the way back to the capital while travelling through Dezhou, the young empress died at the age of 36.

Emperor Qianlong was devastated and mourned the loss of his Empress with great sadness. In his grief he ordered that all of the late Empress’s possessions be enshrined in their original position for 40-years.

Emperor Qianlong would visit her grave every year while writing poems in memory of his lost empress. His love for her was so strong that he took a long time to install a new empress, as none he could find could hold up to what he had lost.

At the age 80, Emperor Qianlong again paid a visit to the Empress’s grave and wrote, “Every autumn, I can’t help but cry when I pay homage to you. I am aging and I don’t wish to live to be one hundred-years-old. It’s comforting to know that we will be reunited in less than twenty years.”

It is said that whenever there were major events the Emperor would visit the grave of his lost Empress to tell her about them. Emperor Qianlong and Empress Fuca were married for 22-years prior to her death but the Emperor loved her for all of his remaining years.