As a valuable source of protein, beans have been cultivated for millennia, starting with the earliest civilizations of prehistoric times. Today, there are countless varieties of beans in all shapes and colors, and some of the healthiest populations are those with a high bean intake.

An abbreviated history of the bean

Neolithic excavations in Switzerland revealed traces of fava beans (Vicia faba). First cultivated in Italy around 4,800 BC, favas are still a favorite in the Mediterranean region.

Chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), a staple of Middle Eastern cooking, were discovered in Egyptian tombs; and all the common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) are traced back to Mesoamerica, with radiocarbon dating placing their origin at 7,000 BC.

Archeological bean findings suggest that the common bean was domesticated separately in three different locations in the Americas, yielding unique Mesoamerican, Andean, and Peru-Ecuador gene pools. Native Americans cultivated many varieties of the common bean alongside corn and squash, together known as the “three sisters,” a trio fundamental to the development of early Mesoamerican civilizations.

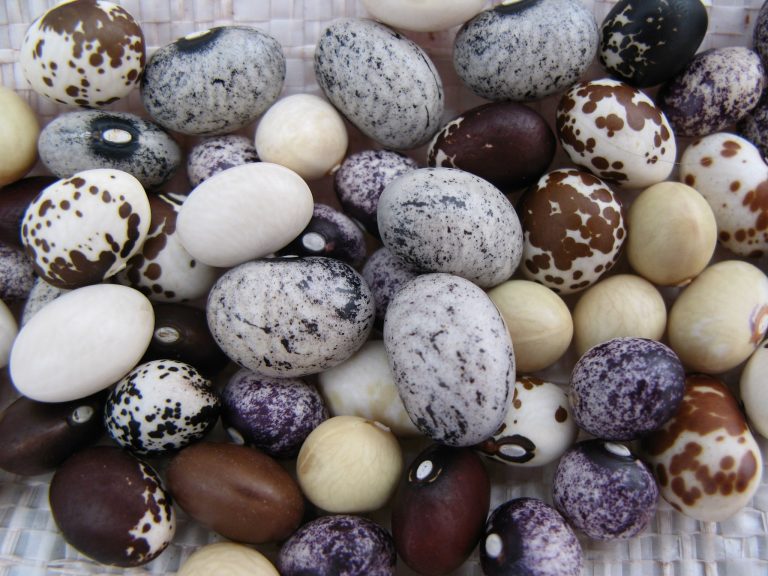

P. vulgaris encompasses the majority of what we call beans, with hundreds of varieties, including black beans, kidney beans, navy beans, pinto beans, and all of what we know as “green beans” — pods with immature seeds. The common bean was introduced to Europe only after Columbus visited the New World in 1492.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The soybean (Glycine max) has been cultivated in China since around 1500 BC.

Beans come from a large family of legumes

Leguminosae is one of the largest families of flowering plants, with 600 genera and around 19,000 species. Its members include not only all the beans, peas and lentils we are familiar with, but also the peanut, which grows underground and is technically not a nut; important agricultural crops like alfalfa and clover; and even trees like the tropical tamarind, whose tangy fruit is used to flavor variety of Asian cuisines; and mesquite, an ancient tree from arid areas of the Americas, with dozens of uses, including its edible pods.

Botanically, legumes are unique in their production of dehiscent dry fruits — or pods — which naturally open along a seam when they dry, and contain the (often edible) seeds — or pulses — that we know as beans, peas and lentils.

Aside from providing a huge variety of plant proteins for both man and beast, legumes are valued for their nitrogen-fixing capabilities. Thanks to a symbiotic bacteria in their root nodules, legumes provide a good source of nitrogen for soil health. They are often used in crop rotation as “cover crops” to replenish depleted nutrients in between plantings.

Beans that are NOT beans

You may be surprised to find that a number of agricultural products we commonly call “beans” are not beans whatsoever. Coffee, for instance, belongs to the family Rubiaceae, which also includes the fragrant ornamental gardenia. Rubiaceae members do produce flowers and fruit, but what we know as a coffee bean is simply a seed.

The same is true for cocoa. This tropical evergreen belongs to the Malvaceae family, which includes okra and cotton. The edible pods of carob — a common substitute for cocoa— however, are grown on an evergreen tree in the legume family and can be rightfully called beans.

Catalpa is a genus of large trees that belong to the Bignoniaceae family. They are commonly called “Indian bean tree” due to the long, thin seed pods they produce with abundance. These seeds are not edible, although they may have some medicinal value.

Castor beans, from which the much-detested castor oil is derived, are produced by a perennial member of the Euphorbiaceae family; which includes a wide range of succulent plants, many ornamental spurges, and poinsettias!

Finally, the intoxicating vanilla bean is produced by a member of the Orchidaceae family. Although the flowers of legumes and orchids may appear similar on the surface, they are completely separate families.

Health benefits of beans

Often referred to as the “poor man’s protein,” beans may not be the first food that comes to mind when carbohydrates are mentioned; but these protein-packed seeds are actually a fabulous carb to add to your diet, without adding inches to your waist!

Like whole grains, beans are loaded with fiber to aid digestion; while they also offer high levels of resistant starch, something found in only a few whole grains — including barley, oats and sorghum. Resistant starch is equally important for digestion, as it supports the gut’s helpful bacteria and promotes the production of short-chain fatty acids, a crucial element in colon health.

Studies have shown not only that bean consumption can significantly reduce the risk of colon cancer, but also that populations with high bean/legume consumption have fewer occurrences of a wide range of cancers and other degenerative diseases.

Beans are also helpful in weight loss efforts. Since the resistant starches are not digested, those calories are not absorbed by the body. In addition, the high protein and fiber content make beans satisfying and help you feel full longer, thus reducing food cravings.

Because high levels of resistant starch equates to a low glycemic load, beans and other legumes are valuable foods in the prevention or reversal of diabetes.

On top of all that, most beans offer a host of other important nutrients, including B vitamins, iron, copper, manganese, and, of course, low-fat plant protein; so what’s holding you back? Ah, yes… the fear of flatulence.

Why beans cause flatulence

It’s true that beans are notorious for causing gas. Let’s look at what is behind (hee hee) the issue, and see what can be done about it.

Intestinal gas is a natural consequence of digestion, which generates odorless hydrogen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and for some people, the explosive gas methane. Odor enters when sulfur — found in common foods such as meat, dairy, eggs, garlic, onions, many vegetables (especially members of the cabbage family), nuts and beans — is present.

Many foods can give you gas; but beans, in particular, contain an indigestible sugar called oligosaccharide. Since we have no enzymes to break down this polymer, a fermentation process begins when it reaches the large intestine. This chemical reaction creates gas, which has only one way out.

To reduce flatulence, one can take a supplemental enzyme called alpha-galactosidase; but this can both increase the levels of galactose in the blood, as well as increase blood sugar; so it is not recommended for everyone.

Reducing flatulence naturally

A more holistic approach is to gradually increase your bean intake. The flora in your gut will naturally adjust, and beneficial bacteria will gain a foothold when you improve your diet. Smaller legumes (like lentils and split peas), and fermented bean products (like tempeh and miso) are a good place to start, as they are easier to digest.

Once you are comfortable adding whole beans to your diet, try to get dry beans rather than canned. Soaking beans overnight helps dissolve the oligosaccharides. Change the soaking water at least once and rinse the beans before cooking to remove the offensive compound. If you must use canned beans, discard the liquid and rinse them before use.

Another trick is to add digestion-enhancing spices. Cumin, coriander, fennel, ginger, turmeric and asafoetida are all commonly used in Indian cooking, a cuisine that uses a variety of legumes in its vegetarian dishes. These spices will not only make your gut happy, your taste buds will be thrilled!

Italian herbs like oregano, thyme, basil and other mints contain volatile oils that ease gas and bloating. Add these to your cooked beans or other dishes served with them.

In Asia, the seaweed kombu is often added when cooking beans to neutralize oligosaccharides. The seaweed is nutritious in itself, and boosts the vitamin and mineral content of your meal. The gas-producing compounds may rise to the surface in a white foam, which you will want to skim off.

READ ALSO:

- Eating Seasonally: 7 Summer Salads That Will Knock Your Socks Off

- Crispy, Crunchy, Savory Seed Crackers – Low-carb, Vegan, Gluten-Free Recipe

- Diet and Depression: 5 Foods to Eat Up When You’re Down, and 5 to Avoid

With over 400 varieties to choose from, beans are easy to incorporate into your daily diet. Try some popular favorites like hummus, falafel, a classic bean salad, or vegetarian bean chili, and I think you will find they are every bit as satisfying as other proteins and starches you may be used to.