Financial Analysis

Historically, fixed-income securities such as bonds — especially the investment-grade core of the market, which includes U.S. Treasuries and high-quality corporate bonds have been a haven for investors looking to limit the risk associated with the stock market.

Not so this year, as 2022 is shaping up to be one of the worst years in decades for bonds.

A devastating year for US bonds

The S&P 500, the most widely followed proxy for the U.S. stock market, has returned a negative 23.6 percent, including dividends, this year through Oct. 6. Over the same period, the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index, the most widely used benchmark for the broad, diversified investment-grade U.S. bond market, has returned a negative 14.8 percent.

What was notable about the recent decline was that the U.S. bond market has had positive returns, before inflation, in all but four years since 1976. Even in 1994, when the Federal Reserve (Fed) raised interest rates six times for a total of 2.5 percent, the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index lost only 2.9 percent.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Long bonds, mainly 30-year U.S. Treasuries, are more sensitive to interest rate changes than one-year Treasury bills. Consequently, the Bloomberg U.S. Credit Long A.A. index lost a staggering 27.7 percent this year through Oct. 6 as the Fed raised the fed fund rate five times from March through September to a range between an upper and lower limit of 3.00 percent to 3.25 percent.

Various developments, from continued supply constraints for goods to a significant shift in monetary policy by the Fed and record-breaking U.S. debt, have combined to wreak havoc in the bond market.

READ MORE:

- Governments Hemorrhaging Foreign Reserves as Geopolitical Tensions Strain Global Economy

- UN Warns Central Banks to Pivot Away From Hawkish Policy

The largest outflow in global bond markets in two decades

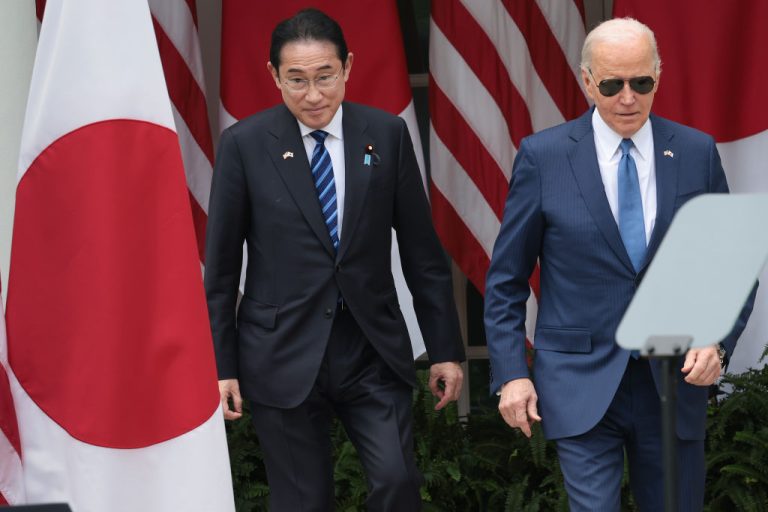

Global bond funds experienced the largest outflow in two decades as the combination of high debt levels, and interest rate hikes by central banks in key G7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) reduced investors’ confidence in governments’ ability to pay back debt.

According to Refinitiv Lipper, global bond funds faced a cumulative outflow of $175.5 billion in the first three quarters of this year, the first net sales since 2002.

Correspondingly, the net asset value of global bond funds slid by 10.2 percent over the same period, the worst slump since at least 1990.

Some key developments in the global bond market include:

- The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasuries, the benchmark for global debt markets, rose to its highest level since 2008.

- Germany’s 10-year yield, which sets the pace for eurozone fixed-income markets, reached its highest point in more than a decade due in considerable measure to a significant tax-cut package.

- The 30-year U.K. gilt yield surged to its highest in almost 25 years before the Bank of England intervened to ease the pressure.

A rising bond yield is dollar bullish

Various developments in the currency markets have added to the upward pressure on bond yields. For instance:

- The U.S. Dollar Index, which measures the greenback against a basket of six peers, is up nearly 17 percent this year.

- Japan recently stepped in to shore up the yen while maintaining ultralow interest rates after the currency tumbled to a 24-year low against the U.S. dollar.

- In the U.K., surprise fiscal policy stimulus — including tax cuts that were later partly reversed — was viewed as running counter to the Bank of England’s monetary tightening, igniting a selloff in global sovereign debt markets and sending the pound to an all-time low against the U.S. dollar.

The G7 as a whole

The bond meltdown has sent the mean 10-year borrowing cost for G7 countries to its highest level in more than a decade, with the average yield surging to 3.15 percent or 1.85 points above its 10-year average. The average rate would be even higher if not for the Bank of Japan’s policy of keeping its benchmark yield below 0.25 percent.

The current G7 inflation rate average of 7.2 percent is significantly higher than an average of 1.7 percent recorded over the past two decades. Rising inflation is reflected in the increasing prices of the different commodity groups in the G7 countries, most notably, the price of electricity, gas, and other fuels, which skyrocketed in 2022, along with transport costs.

The G7 average official interest rate is about 1.75 percent after hovering around zero over the past two years. Rampant inflation suggests that G7 countries will further tighten monetary policy in the coming months to subdue consumer prices, keeping upward pressure on bond yields.

The shadow banking sector

Analysts have flagged lingering stability risks in the U.K.’s shadow banking sector. These non-bank financial institutions include bond funds, pension funds, and companies involved in cryptocurrencies that act as lenders or intermediaries outside the traditional banking sector.

The capital requirements of shadow banks are often set by the counterparties that they deal with rather than regulators, as is the case with traditional banks.

As interest rates rise and liquidity lowers, these shadow banks could run into trouble if they face margin calls by their lenders and need to come up quickly with new collateral they don’t have while not receiving payments from their debtors.

Such events have helped drive the bond-market volatility gauge, known as the Merrill Lynch Option Volatility Estimate or MOVE Index, to the second-highest reading in its history, bested only by peaks during the 2008 global financial crisis.

READ MORE

- How the Biden Admin Could Restrict Independent Contractors: Explainer

- Alongside Push for Digital Currency, Gold Keeps Its Long-term Value

- The Understated, Yet Massive Power of Asset Management Firms BlackRock and Vanguard

A yield curve inversion may be signaling a recession

Another concerning trend in 2022 is the shape of the U.S. Treasury yield curve. Under normal circumstances, bonds with longer maturity dates yield more, resulting in an upward-sloping yield curve. This state reflects a return premium for the more significant uncertainty in lending money for a more extended period.

As of Oct. 6, 2022, the yield for a ten-year U.S. government bond was 3.89 percent, while the yield for a two-year bond was 4.3 percent. This unusual occurrence, called a yield curve inversion, reflects economic uncertainty. More to the point, an inverted yield curve has historically been a reliable indicator of an upcoming economic slowdown or recession.

In fact, since World War II, every yield curve inversion has been followed by a recession within a 6–18-month window.

A ‘structural absence of demand‘

Even if the Fed eases on its rate hikes in response to high unemployment and a weak economy, this may not translate into strong demand for government backed-securities as U.S. Treasury bonds are experiencing what JPMorgan analysts describe as a “structural absence of demand.”

JPMorgan strategists Jay Barry and Srini Ramaswamy write that the three main buyers of U.S. government debt — the Federal Reserve, commercial banks, and foreign governments — have eased their purchases significantly.

Using data from the Federal Reserve, they determined that:

- The Federal Reserve dropped its Treasury holdings by about $180 billion this year as a part of its monetary tightening program to fight inflation and cool the economy.

- The collective deposits of commercial banks have fallen by $60 billion in the past six months compared to the same period last year, after growing more than $700 billion between 2020 and 2021

- Foreign governments’ official holdings have dropped $50 billion over the past six months.

Any of these factors would undermine demand for U.S. Treasuries, but the instance of all three points to an unprecedented drop in demand.

“The reversal in demand has been stunning as it has been rare for demand from each of these three investor types to all be negative simultaneously,” wrote Barry and Ramaswamy.

What’s next?

Recent data only reinforces the likelihood that the Fed will continue to raise rates during the next meeting on Nov. 2 to contain inflation as the consumer price index (CPI) unexpectedly climbed 8.3 percent for the 12 months that ended August 2022 as rising shelter, food, and medical care costs offset a drop in energy prices.

The U.S. added 263,000 jobs in September, the smallest gain in 17 months, though just enough to keep Fed policymakers on track.

The consensus of most economists calls for a 75-basis point rate hike in November, followed by a 50-basis point rate hike in December, with the Fed fund rate sitting around 4.25 percent.

The risk to this outlook is on the downside. The threat of a recession looms large, especially if policymakers overreact to strong economic data. Furthermore, the surging U.S. dollar remains a specter, and the Fed risks instability in financial markets with every rate hike.

What this means for the bond market is that if unemployment remains low and Fed rate hikes continue as expected, the retreat from U.S. Treasuries could also continue, raising the cost of borrowing for governments.

On the other hand, if unemployment grows, it could signal the Fed will ease its rate hikes which is good news for the bond market.