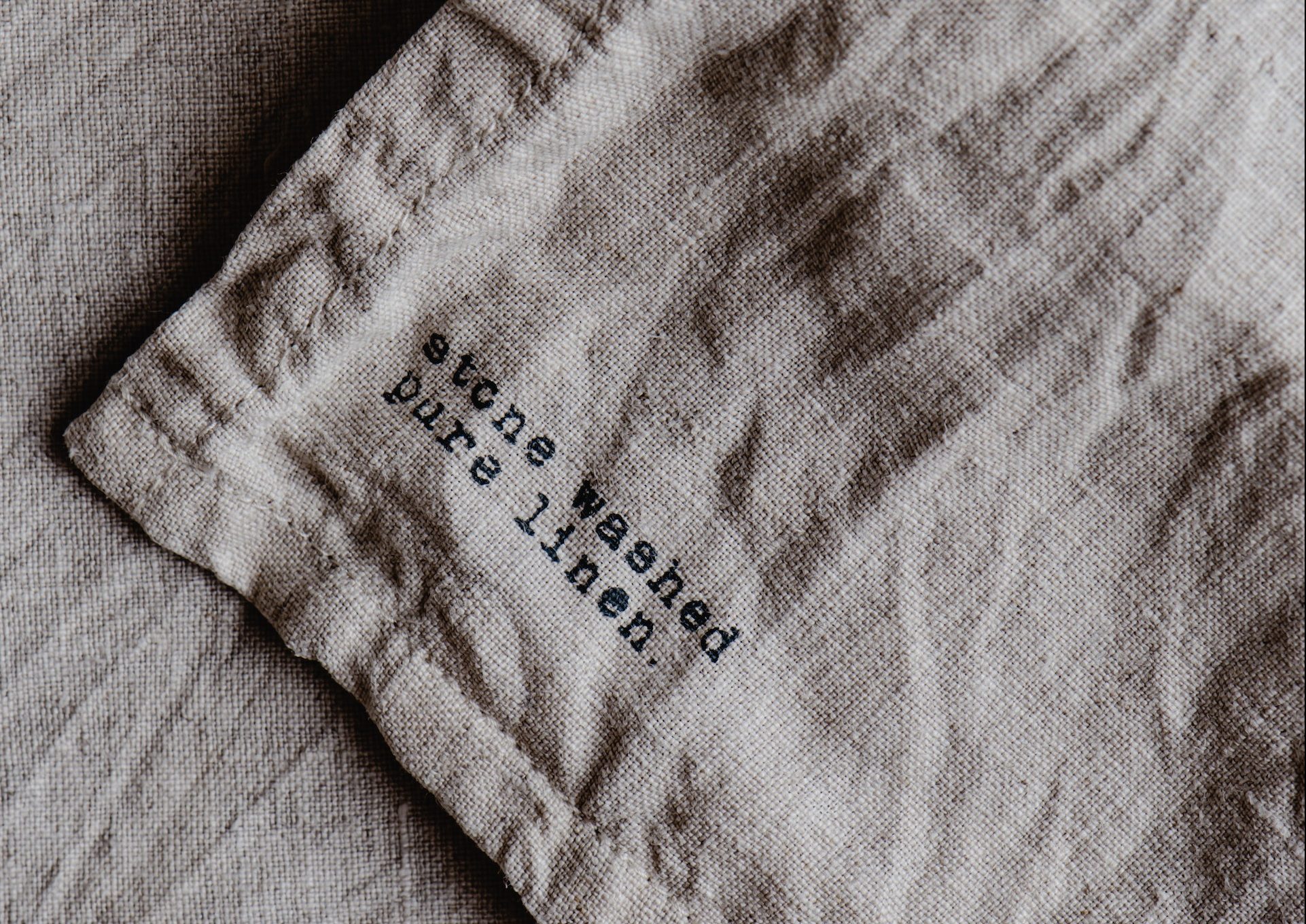

Continuing our series on natural fibers, today we will look at one of the most ancient fibers used by man that still has broad appeal today. It is more absorbent than cotton, and also dries more quickly. It has the remarkable ability to thermoregulate — making for comfortable clothing in any climate. It is hypoallergenic, and it holds its shape without shrinking or stretching. Although it wrinkles easily, it can take a very hot iron; and if it gets dirty, it is easy to clean.

Linen fabric, sustainably produced from the long stem-fibers of the flax plant, is soft, durable, and often considered a luxury. Let’s take a look at all the work that goes into producing this extraordinary fiber.

The flax plant

Flax, (Linum usitatissimum) is an unassuming annual that has been cultivated in temperate climates for at least 5,000 years. The plant not only produces nutritious flax seed and flaxseed oil; the whole stem and root are used to make one of the most comfortable natural fibers in the world. This low-maintenance crop is extremely sustainable. It requires little water and no fertilizer or pesticides.

Traditionally, flax seed was sown by “broadcasting” or rhythmically tossing the seeds over the field by hand. For even distribution, an experienced hand was required. It may take up to one month for flax seed to germinate.

Around 50 days after germination, the plant begins to bloom, with small, cup-shaped flowers that last one day each. This continues for around 20 days, and after another 30-some days the seeds mature and the 36-40 inch plant is ready for harvest.

Linen in history

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Wild flax was also apparently used for fabric in prehistoric times. Remnants of linen fibers estimated to be 30,000 years old were found in a cave in Southeastern Europe, and 10,000 year-old fibers were found in a Swiss lake. Ancient Egyptians used linen as a special covering for mummies, since it symbolized light and purity, and it was considered so valuable that it could be used as currency.

In Mesopotamia, linen was regarded as a fine fabric — worn by priests or the wealthy, and used to adorn religious statuary. Gradually, linen became one of the most common natural fibers, and was produced throughout much of Europe and the American colonies.

With the advent of the cotton gin, however, linen lost its rank. The laborious processing required to produce the fiber made it impossible to compete with mass produced cotton. Today linen comprises only one percent of the natural fiber industry.

Processing flax for linen

Harvest

The whole flax plant is pulled once the seeds are mature. This — as opposed to cutting — yields a longer fiber because it includes the root. The whole plant also stands up better in the next step. Pulling can be very strenuous work when done by hand, but some manufactures now use machinery to uproot the whole plant.

Stooking

The uprooted plants are gathered into bundles called ‘beets’ to dry in the field. This technique ensures more even drying than laying the plants in the sun, and helps to discern quality. The best flax will dry to a lighter color than the lower quality plants.

Rippling

Before turning the flax into fiber, the seeds are removed from the dry stems in a process called rippling. The plants are pulled repeatedly through a rippler to get all the little, round, seed heads off. These are then crushed to release the seeds, the chaff is winnowed away and the seeds are ready for use or storage.

Retting

In order to harvest the actual fibers, one must dissolve the pectin and cellular tissues that bind them together. This is a water process called retting, which can take up to five weeks.

A speedy retting is accomplished through submerging the dried flax in a marsh or bog, where the naturally-present bacteria go to work on the woody portion of the stem, called the boon. This fermentation process takes only about one week, so one should check the fibers daily.

This is a fairly stinky procedure, however, and many opt for dew-retting instead, where the plants are laid out in the field, exposed to the weather. They must be periodically turned for a uniform product. This method takes more space and time (up to five weeks), but does not require as strict attention.

Retting is complete when you can reveal the separate fibers with some bending of the stalk. If the stalk remains intact when bent, more retting is required. Over-retting will result in broken fibers.

Some growers are also experimenting with the addition of bacteria to enhance dew retting.

Breaking and scutching

The retted flax must be dried again (stooked) before the next step. Once they are completely dry, the loosened fibers can be separated from the woody stems. Traditionally, handfuls of flax were beaten with wooden blades from the bottom to the top, with the stem fragments (called shives) falling away to be collected for other uses — like animal bedding.

Next, a large wooden “scutching knife” is used to manually scrape away more of the boon and soften the fibers. This strenuous work is mostly done by industrial machinery today.

Hackling

Finally, the fibers are prepared for spinning in a process called hackling. A loose-tooth comb is used first to remove more boon, and then a finer-tooth comb is used to polish and split the fibers. The shorter fibers come off in the hackle and become lesser-quality linen, with the shortest of those, called the “tow.”

The tow can still be spun, but it is more like wool; while the longest fibers will be spread out into large gauzy fans and wrapped around a distaff for spinning. Alternatively, the aligned fibers can be simply wrapped straight into a linen towel, which can rest in the lap of the spinner.

Spinning

Spinning flax into linen — from either a distaff or from the lap, with either a spinning wheel or a spindle — requires moisture. Dampening the fibers activates the remaining pectin and helps them stick together, giving a smoother thread. This can be accomplished by periodically dipping the fingers into a cup of water.

Fibers that come from the stem of a plant are called bast fibers. Since bast fibers are so long, they don’t require as much twist as shorter fibers, like wool or cotton. The thread can be fed quickly onto the bobbin with minimal treadling of the wheel.

Scouring

The resulting fine thread still has some remaining pectin, and requires scouring. On a small scale, this is accomplished by simmering the bobbin-contents in a big pot of water with equal amounts of borax and dish soap. One hour of this will turn the water dark like coffee. The process is repeated until the water remains clear, then it is rinsed by simmering in plain water for one hour.

Scouring not only makes the linen whiter and softer; it also opens up the cells so that it can accept dye.

Organic linen

While it is rare to find certified organic linen; as you can see, thus far in the process, linen is incredibly pure and natural. It is only when the fabric is treated to become “wrinkle free” or fireproof, whitened with chlorine bleach, or chemically dyed that unfavorable elements are introduced into linen.

Bast fibers are actually considered the most sustainable plant fiber, and linen itself retains its beauty and integrity for decades. All things considered, a little luxury like linen is well worth the investment.