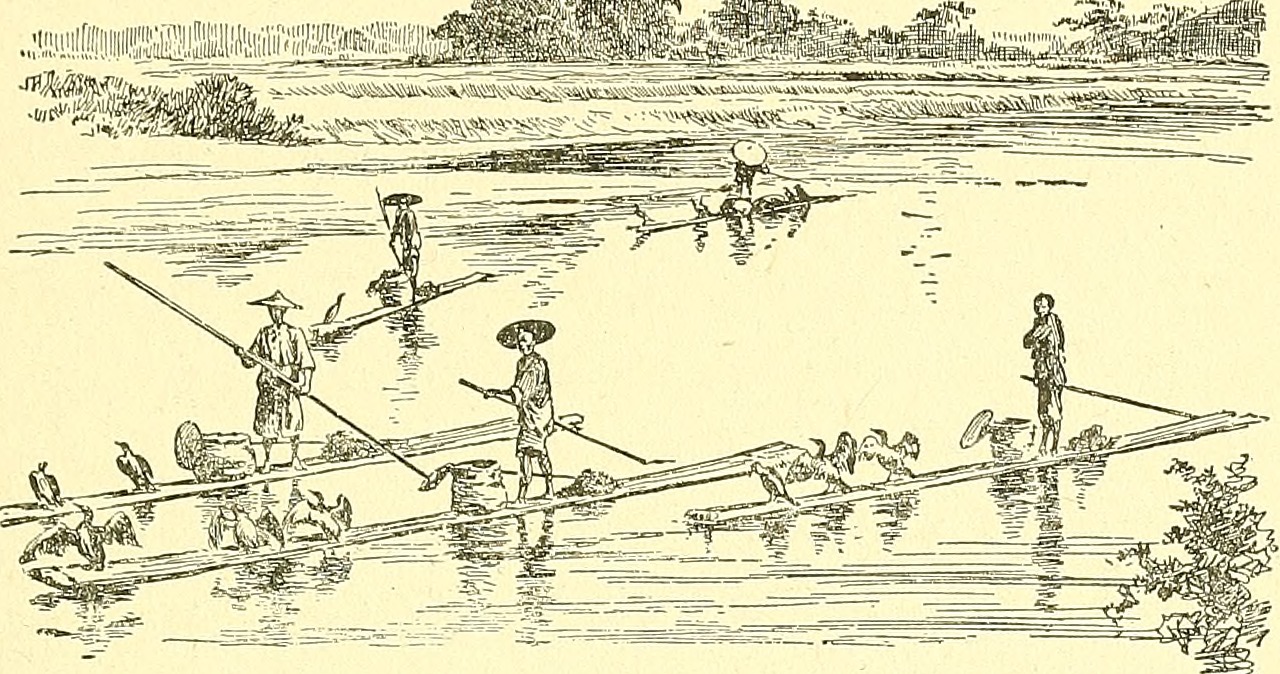

On the ancient waters of the Lijiang River, surrounded by the enchanting peaks of the Guilin Mountains, a spellbinding scene continues to unfold, although less frequently than before. Veteran fishermen on bamboo boats churn the surface of the water, where dark-feathered birds dive with alacrity, chasing fish with remarkable precision.

For more than 1,300 years, men and birds have cooperated in the art of traditional fishing. Before the introduction of modern fishing tools, this enduring collaboration was a means for men to earn a living, and an opportunity for birds to secure a caring owner.

Let’s explore this traditional fishing technique, how it sheds light on the relationship of the ancients with nature and how it is used today.

An uncertain and distant origin

The first-ever mention of fishing with cormorants was made in the Book of Sui, a historical book of the Sui dynasty (581-648) completed during the succeeding Tang dynasty.

Interestingly, the book describes this activity as a practice carried out by the Japanese, not the Chinese. Whether it originated in one of these countries, or in both at the same time, is still a matter of debate. What is certain is that the technique was widely used during the Song dynasty (960-1279), and very popular by the Ming dynasty many hundreds of years later.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The technique of cormorant fishing has likewise been used in the West, in places such as Greece and North Macedonia, where it is still practiced by some veterans. England and France also adopted the technique, not for subsistence, but as entertainment, especially for European royalty during the 16th and 17th centuries.

There is evidence that cormorant fishing has been practiced for centuries in Peru. In fact, the Uru people of Peru have long trained and worked with a species of cormorant known as the neotropical cormorant (Nannopterum brasilianum), which is exclusive to the American tropics and subtropics.

The Japanese, meanwhile, employ the Japanese cormorant (Phalacrocorax capillatus), a yellow-billed species that inhabits areas from Taiwan, northwards through Korea and Japan to the Russian Far East.

In China, the great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) is popular among traditional fishermen on the Li River. This species, which varies greatly in size, is mostly black and breeds in the Old World (Africa, Europe and Asia), Australia and the Atlantic coast of North America.

The skillful cormorant

Cormorants are medium-to-large aquatic birds whose bodies are more adapted to being in the water than out of it. Their short wings, usually adorned with dark feathers, are designed to facilitate underwater movement, complementing the propulsive function of their webbed toes.

They are fish-eaters by nature, and their long, thin beak, coupled with a remarkable speed in cutting through the water, allows them to be highly accurate in capturing their prey. Depending on the species, some cormorants can dive to incredible depths (up to 45 meters) and remain under water for up to five minutes.

These birds are also successful at fishing in the dark, which has been thought to suggest alternative forms of prey detection in addition to visual ones. Unlike most birds, cormorants’ feathers are not completely waterproof, which makes it easier for them to dive and swim. Once on land, they spread their wings to dry off, in a spectacle that is unique to them.

Cormorants usually live along the coasts, although some species can be found in both coastal and inland waters. Their habits – not their physiology – change to adapt to their environment, which explains why, in winter, Greenland cormorants eat almost twice as much as their congeners in Normandy, all while maintaining the same body temperature.

The traditional technique

Working cormorants usually start their training as hatchlings, either through socialization with older companions or through a reward system that teaches them to cooperate with their owners. Once they are four months old, they are ready to participate in the task, fishing actively until the end of their lifespan, which is approximately 20 years.

Before the cormorants are allowed in the water, fishermen tie cords around their necks – loose enough to allow them to swallow small fish, but tight enough to prevent larger fish from passing beyond the gullet. Once the bird catches a large fish, it instinctively returns to the boat or raft, where the fishermen remove it from their throat and compensates them for their efforts.

In this millennium-old partnership, birds and humans can catch several dozen fish a day, solidifying an enduring bond of cooperation, companionship and survival.

Not just birds, but companions

Although tying the birds’ necks and rewarding them with a smaller prize than their catch may seem cruel and unfair, both parties benefit from this collaborative relationship: humans earn a living while the birds have all their basic needs met.

This interaction is based on the ancient’s belief in living in harmony with nature. In the particular environment of ancient China, where the philosophies of Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism shaped society’s thinking and behavior, people respected all forms of life. However, they also recognized nature’s role in human survival, so they did not shy away from using the resources it offered them to thrive.

Like many traditions of the past, cormorant fishing is a matter of human dependence on nature, but there is also something unique about it. Given the birds’ relatively long lifespan and their training from a young age, fishermen also become accustomed to the company of their birds. For some fishermen, cormorants are like their children.

This is why many fishermen use the Chinese colloquialism “养命仔” (yǎng mìng zī) when referring to their cormorants, as it traditionally refers to a son who lives to support his parents. In the hearts of traditional fishermen, affection, but above all respect, for their birds abounds.

A nearly lost tradition

Few traditional fishermen are left in the world, especially in China. Modern fishing tools have rendered this traditional technique obsolete, and the men who dedicated their entire lives to this craft sometimes continue to do it, but now before the eyes of numerous spectators, driven by the tourist industry.

On the picturesque waters of the Li River in Guilin, bamboo rafts that once carried men and birds for fishing are now propelled by younger fishermen ready to give a live performance to the beat of more modern music. Cormorants still accompany the young fellows, but are now employed as part of the show.

Without the opportunity to closely work together with the birds, and with a money-driven industry – performances are said to increase the annual income of villagers by at least 20 to 30 thousand yuan – it remains to be seen whether the younger fishermen still honor and regard the birds as their ancestors did. But one thing is certain: as long as traditions are preserved, harmony with nature can prevail.