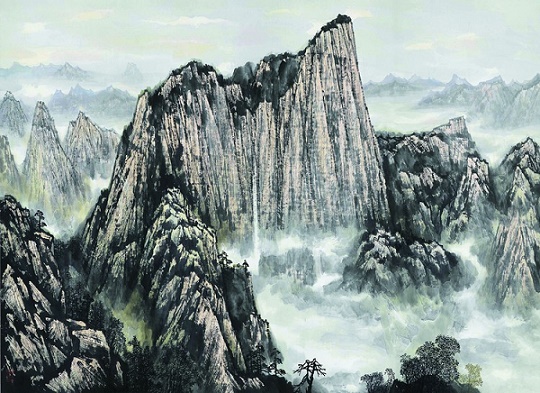

In today’s Anhui Province of eastern China, there is a scenic locale known as Mount Baochan (褒禪山), which one might translate as “Zen Mountain” for its association with the Buddhist order.

Within Baochan Mountain is the famed Huayang Cave, which is known not just for its elaborate subterranean rock formations, but also as an ancient political and philosophical allegory, written by the storied Wang Anshi (王安石), the ambitious and forceful — yet ultimately unsuccessful — chancellor of the Northern Song Dynasty (AD 960–1127).

A group of five hikers, as the short text goes, entered the cave while on an excursion. The sights inside the cave were well worth the long trek, and, it was said, became only more wondrous the further and deeper one ventured. However, though many a sightseer visited the entrance to leave their names, only a brave few dared risk the challenging trip necessary to discover the natural secrets hidden within the dark, cold interior of Huayang.

The five men, it was written, all carried torches sufficient for the difficult journey. “As we ventured deeper, progress became more difficult, but the scenes we witnessed became increasingly extraordinary,” Wang wrote.

But upon reaching less than one tenth of the distance that “those who enjoy risk-taking might attempt,” one of the hikers grew anxious. “If we don’t leave soon, our torches will go out,” he said, weary of pressing on.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Thus, the group had no choice but to turn back. Some expressed their disappointment with the lone dissenter, who they felt had spoiled the journey.

Wang lamented:

“Looking at the stone walls on either side, there were already very few people who had come here to inscribe their names. Even deeper into the cave, still fewer visitors likely ventured. When we decided to turn back, I still had a lot of stamina, and the torches could still provide illumination. After we re-emerged, some complained about the person who talked us into leaving, and I too regretted coming out with him, unable to fully savor the delight of exploring the cave.”

Force of character

Wang Anshi’s text is simple and, like many famous classical Chinese works, rather short. But it directly addressed the problems he and his superior — the emperor of Song China himself — faced in governance, and it also reflected the attitude Wang imagined could overcome those problems.

MORE FIGURES FROM ANCIENT CHINA

- From Prisoner to Prime Minister: Guan Zhong and the Hegemony of Qi

- Su Shi, the Ancient Poet Who Put the People First

Among historians, the Song Dynasty is known for its tolerant and relatively open political scene. Its founding emperor Zhao Kuangyin, despite being a general who took power in a military coup, saw the importance of civil administration. He forbade all his successors from putting scholars to death, even if they dissented against the crown.

As a result, many of the eminent figures of Chinese politics and philosophy are to be found during the Song, an empire that overall enjoyed robust governance, economic prosperity, technological progress, and even strong defense despite not explicitly focusing on development of the military or territorial expansion.

In the late 1000s, when Wang Anshi was active, he saw that the Song’s century of good fortunes were not guaranteed to last forever. “We cannot always depend on the gifts given to us by Heaven,” he once wrote.

A skilled bureaucrat who saw the future of the Song state as his life’s mission, Wang convinced the emperor that he had the tools it took to create that future.

- Returning to the Peach Blossom Spring

- ‘A Sparrow May Be Small, But It Has All the Five Organs’ (麻雀雖小,五臟俱全)

As he would eventually write in his travelogue to Mount Baochan, Wang stressed the need to see things through to the end in order for the most splendid results to be achieved:

“The ancients, when it came to observing the heavens and earth, mountains and rivers, plants and trees, insects and fish, birds and beasts, were able to gain general insights into natural principles,” he noted.

“This was because they probed and contemplated issues in depth and breadth,” and, moreover, had the determination to reach the “marvelously grand, precious, unique, and extraordinary landscapes throughout the world often lie in places that are perilous, remote, and rarely visited by man.”

The imperative of reform

Wang Anshi was a genius in his own right, having passed the arduous imperial exam at age 21, and served as a judge and treasury official. He was a contemporary of many great men, such as the famed historian and minister Sima Guang, the brilliant poet Su Shi, calligrapher and essayist Ouyang Xiu, as well as Cheng Hao, an important representative of the new interpretations of Confucian ethics and social philosophy.

Before reaching the imperial capital, Wang served in local posts, where he wasted no time in devising laws and measures to help the common people.

In Ningbo, a coastal community, Wang offered poor peasants low-interest government loans that they could use to buy seeds in the spring rather than rely on the wealthy who would charge them unaffordable interest rates. In the autumn, the farmers could pay back their loans at the government rates — and the local economy flourished. He also invested in public water works, which paid off at an even greater scale.

In the 1060s, Wang was invited to the imperial capital at Kaifeng, having gotten the favor of the crown prince. In 1068, the prince became emperor. The next year, he granted Wang chancellorship, and gave him free reign to do what he desired most: to guarantee the people’s welfare and secure the lasting reign of the Song Dynasty.

With his astute grasp of macroeconomic and financial principles, Wang immediately set out to rectify what he saw as drains on the state and people. For instance, he created a more efficient system of military conscription to maintain a standing army that could receive training and maintain its force structure, yet not unduly impact the civilians who, in times of need, would be called up for duty.

Additionally, he upscaled the policies he implemented so well in Ningbo, intending the poor commoners to be able to take out government loans to buy seeds, land, or anything else they needed to make a living for themselves and in time contribute to the state coffers.

The “New Laws” (新法) or “Xining Reforms” (熙寧變法) were almost unprecedented in Chinese history. And the Song Dynasty had the economic conditions and political culture needed if such a massive effort was to succeed.

But Wang would soon find out that not everything can be done exactly to plan.

Human error

Wang’s New Laws had their detractors from the very beginning. Apart from wealthy landowners, whose interests stood to be impacted by the reforms, virtually all of the conservative ministers, as well as the emperor’s mother — the Empress Dowager — were skeptical of the drastic changes he proposed. Some even directly argued that the peasantry should not be recklessly given the means to own land, as it would upset the traditional social hierarchy.

The emperor and his chancellor were prepared for dissent. But they pressed on.

Modern views of Wang Anshi are mixed, but a middle-of-the-road assessment would acknowledge that many proposals of his were indeed required, but the problem lay in implementation.

Others had attempted overhauls of the Song imperial government before Wang. During the reign of Emperor Renzong (1022–1063), the statesman and literati Fan Zhongyan (范仲淹) created a ten-point reform program.

But where Fan advocated first and foremost that competent and moral individuals be cultivated for office, none of Wang Anshi’s proposals involved considerations of moral character, and hardly had a human element — they instead concerned themselves solely with socioeconomic matters.

And as conservative opposition to the New Laws grew, Wang ensconced himself in a faction of yes-men, the so-called “New Party,” many of whom agreed with him seemingly unconditionally.

Wang’s political path had sad impacts on his personal relationships. As an imperial scholar and official, Wang lived near the great minister and historian Sima Guang (司馬光), and the two were inseparable friends early in their careers.

Yet Sima, a conservative by nature, could not see any good in the Xining Reforms, and neither did Wang have the tact or ability to come to any kind of compromise with his colleague.

In three letters to Wang, Sima criticized his overly stubborn character, rash demand for instant change, and single-minded focus on money as the core of his policies.

Wang’s response was simple: All he did was for the sake of the emperor, and he would pursue his aims irrespective of whether or not he could succeed.

Moreover, he wrote curtly, anyone who got in his way, especially the conservative scholars who spent their days on empty philosophizing, ought to be fired and banished.

Such was Wang’s determination that he became known for the so-called “three ‘no needs’”:

“There is no need to fear heavenly changes,” he declared, in response to the traditional Chinese belief that man must follow the Way and abide by nature.

Further, there was “no need to adhere to the customs dictated by our ancestors,” and finally, “no need to heed the criticisms of others.”

This attitude, together with his backing from the emperor, allowed Wang Anshi to get his way. But his failure to secure any kind of coalition with the other great ministers and scholars of his time would lead to the demise of his reforms and the end of his career.

Trickle-down effects

Not everything was Wang’s fault. Much of the criticism levied against him was born not of genuine concern for the longevity of the Song empire, but out of a simple dislike for the chancellor personally, as well as vested elite interests.

Confucius once said, “the superior man is catholic [or open-minded] but not partisan.”

Yet in the Song court, opposing the “New Party” led by Wang was an “Old Party,” headed by the now-embittered Sima Guang.

Unable and uninterested in resolving these growing divisions, Wang Anshi increasingly sought the company of those who would unquestioningly follow his orders.

As Wang’s policies required a ballooning corps of government functionaries to implement, opportunists flocked to his wing. Figures like Zhang Dun and Cai Jing, whose names eventually made it into the historical annals as noted treacherous officials, held up the banner of the New Laws and loudly sang its praises.

Beyond the imperial center, throughout the country, Wang’s well-intended policies, like a badly planned franchise, often took on a character quite different from what he had intended.

- The 10 Admonishments of Imperial Official Lin Zexu (Part 1)

- The 10 Admonishments of Imperial Official Lin Zexu (Part 2)

For instance, self-serving local officials, instead of lending out money to those truly in need, set up rackets in which they coerced affluent members of their communities to borrow money. In so doing, the officials could guarantee that the loans and interest would be paid, and rack up bogus political achievements that would gain them the favor of higher officials.

In general, the New Laws focused too much on increasing state revenue, unintentionally bloating the government and at times putting officials in economic competition with the common folk.

Some of Wang’s other policies, such as the military reform and a civil conscription redux, were actually working as intended, but needed time to see results, either for the government or the people.

In 1074, a major drought hit China. The conservative Old Party jumped at the chance to evict Chancellor Wang, and, under the sheer pressure from the ministers below and his mother the Empress Dowager, above Song Emperor Shenzong — Wang’s closest, and perhaps only real ally — was compelled to exile him south, to today’s city of Nanjing.

A year later, the emperor called Wang back. But it was too late. The former chancellor had no welcome in the Song capital, and in 1076, was again banished to the south, where he would remain for 10 years until his death.

Legacy and lessons

Unlike many other failed figures of ancient China, Wang Anshi is neither seen as a villain or a tragic hero, but rather a man of single-minded ambition who had the skill but not the tact for his mission.

In addition, his personal character reflected his strengths and weaknesses in government. Wang was an avid reader and a hard worker, writing nearly as prolifically as he read. Yet so consumed was he by his love of study that he often went without proper meals, grooming, or even bathing, to the disdain of those familiar with him.

At the same time, Wang’s dedication to the welfare of the Song is unimpeachable, and he was an accomplished poet and calligrapher. During his retirement-in-exile, he devoted himself to the arts, and studied Buddhism and Daoism. Unlike his doomed relations with Sima Guang, he developed a friendship with one of his political detractors, the great poet and official Su Shi (蘇軾), who himself had been fired and exiled for opposing the New Laws.

Wang appears to have been aware of — and resigned to — his failure. In his account of the outing to Mount Baochan, he wrote:

“Having the strength to achieve one’s goal [yet falling short] is something that others might ridicule, but from a personal perspective, it is a matter of regret. If one has exerted their greatest will but still falls short, they can have no regrets. Who would then mock them? This is what I have learned.”

In the decades that followed Wang’s death, debate and infighting over the implementation of the reforms spiraled out of control. In his ire, Sima Guang — who replaced Wang — had the New Laws completely abolished, only for the young emperor Zhezong to reinstate some of them in 1093. The back-and-forth only fostered social chaos and further bickering in the court between the conservative and progressive factions.

Eventually, the Song Dynasty lost the ability to either govern itself effectively or ward off threats from nations to the north. In 1127, a surprise raid by the Jurchen Jin Dynasty, striking at the Song capital in Kaifeng, saw the capture of the emperor and much of the imperial court. The surviving Song authorities were forced to retreat south, and would never recover from the blow.