Many Americans are familiar with the first few lines of “The Star-Spangled Banner” — “O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light/What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming” — and possibly also with the difficulty of singing it due to the broad range required of the song. But common knowledge of our national anthem may not go much further than that.

While many may assume that the lyric depicts the Revolutionary War that allowed the original Thirteen Colonies to break away from British rule, it refers neither to the struggle for independence, nor was it even officially America’s anthem until less than a century ago.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was originally written by Maryland district attorney Francis Scott Key during the British blockade of Chesapeake Bay in the War of 1812, over 40 years after the colonies declared independence from Britain on July 4, 1776.

The war, started by the U.S. in an attempt to take then-British Canada and end an array of predatory economic and diplomatic behavior by the British Empire, had gone badly. The British fleet of 500 ships more than dwarfed the U.S. Navy, which had just 17 vessels at the beginning of the conflict. The invasion of Canada faltered, and British forces were able to operate with impunity along the border and coast (America had not yet expanded to the Pacific Ocean).

The siege of Fort McHenry

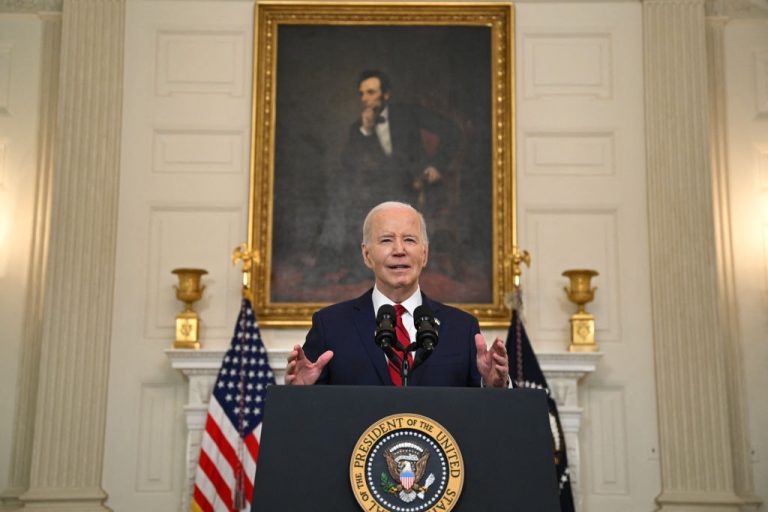

On Aug. 24, 1814, the British attacked Washington City, as the capital was known at the time. The White House was looted and burned. In one of the less glorious moments of U.S. history, the British managed to hold Washington for 26 hours. Only a hurricane and subsequent storm evicted the invaders and put out the fire.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

At the beginning of September, the 35-year-old Key boarded a British ship to negotiate the release of an imprisoned friend, as described by Smithsonian Magazine. A British officer granted his request, but also informed them that the release would be meaningless as the fleet anchored in the bay was about to inflict a serious defeat by taking Fort McHenry, located on the outskirts of Baltimore.

The fort occupied a crucial point in Baltimore’s defense, making it a natural target for the British. After contemplating a land assault with their roughly 5,000 men available, British commander, Col. Arthur Brooke, opted to bombard Fort McHenry instead of trying to attack the fortification directly.

Because Key had learned of the British plan, he and his companions were detained on the ship they had boarded. From this vantage point, Key witnessed the bombardment of the fort through the night of Sept. 13 and Sept. 14.

Nearly 20 British vessels took part in the siege, firing more than 1,500 cannonballs at Fort McHenry. Munitions included an early type of powered missile, the recently developed Congreve rocket. These, fired from the HMS Erebus, would inspire the “rockets’ red glare” that Key wrote into the lyrics.

Holding the line

Aside from rainy weather that dampened the effect of the British bombs and rockets, Fort McHenry was able to withstand the siege because of robust architectural preparations made prior to the Battle of Baltimore. The Americans had scuttled 22 ships in the bay to impede the movement of the British fleet, and the installation of cannons at the fort meant that the British could only fire their own guns and rockets at the longest possible range, diminishing their accuracy.

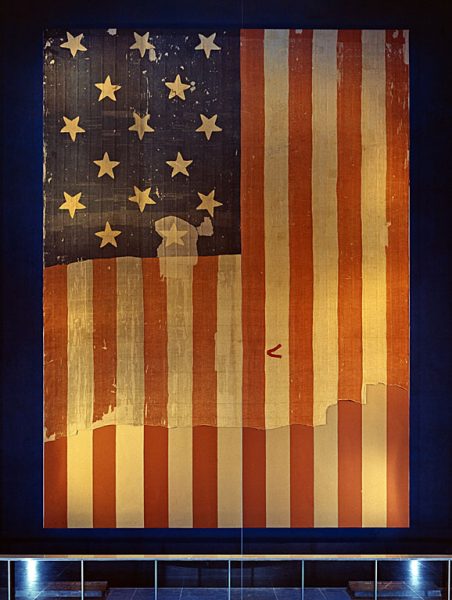

Maj. George Armistead, commander of the fort, had also ordered the weaving of a large American flag, which would be flown from the ramparts.

“We have no suitable ensign to display over the Star Fort, and it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance,” he told a superior officer.

The flag measured 40 feet by 34 feet, and was emblazoned with 15 red stars and 15 stripes representing the original colonies and the two states that had been admitted to the Union since the end of the Revolutionary War.

Another flag, 25 feet in length, was created as a storm flag, which ended up being the one flown through the night of the bombardment.

Watching the battle from the bay, Key was convinced of a coming British victory. “It seemed as though mother earth had opened and was vomiting shot and shell in a sheet of fire and brimstone,” he later wrote.

To his surprise, when morning came the troops manning Fort McHenry had managed to keep the U.S. flag flying. The British had run out of ammunition and had to call off the attack. Still held on the British ship, Key took out a letter and penned a poem on its back to capture the event. A relative serving in the U.S. forces titled the poem “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” It was printed in the Baltimore Patriot, where the publication informed readers it was meant to be sung to the tune of a popular English drinking song.

Becoming the national anthem

Weeks later and after the British fleet had withdrawn, the lyrics had gained broader renown, and was now known by its current name, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Four Americans died in the defense of Fort McHenry, including a black soldier and a woman carrying supplies to the fort. One British cannonball penetrated the fort and threatened its magazine, but failed to detonate.

Throughout the 19th century, the song gained in popularity; however, it was not officially made the national anthem until the passage of a federal law in 1931. Prior to that, the United States had no official anthem. The law was only passed after an issue of the “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” cartoon inadvertently brought attention to the lack of an anthem, causing 5 million people to petition the government and raise “The Star-Spangled Banner” to official status.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” has a total of four stanzas, though only the first is typically sung. The second stanza describes the appearance of the flag as it becomes visible in the morning light; the third depicts the hopelessness of the British assault; and the fourth confirms the U.S. victory, foreshadowing “In God we trust” (added to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1956) with its line “And this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust.’”