Governor of Massachusetts Charlie Baker, a Republican, activated the National Guard on Sept. 13 to help fill a shortage of school bus drivers in his state that has left some school divisions resorting to offering families substantial cash benefits to drive their kids to class.

In a Press Release by Baker’s office, the Governor authorized the deployment of as many as 250 members for the task, noting 90 will begin immediate training on Sept. 14 for the role.

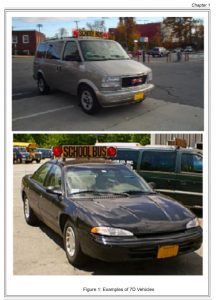

The Guardsmen will complete vehicle training and meet the statutory requirements of a class of vehicles known as School Pupil Transport Vehicles (7D) under Massachusetts law.

In the state’s manual for 7D, it defines the class as a passenger vehicle with a Gross Vehicle Weight under 10,000 pounds that can seat 10 passengers or less, meaning Guardsmen will likely be transporting students via small cargo vans rather than the archetypal yellow machines.

An article by the Wall Street Journal says districts across the country are facing a driver shortage, noting a decline in personnel after, “Some drivers resigned over pandemic-related safety concerns or new Covid-19 vaccination requirements.”

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The article also says Massachusetts school districts have been trying to recruit drivers in advance of the new school year, citing the Boston Public Schools district as saying only 57 percent of busses arrived on time during the first day of classes.

However, that statistic was up from 43 percent a year earlier.

A blog post by Hop Skip Drive, a service that provides alternative transport to school children, attributes the driver shortage to low pay, part time hours, a barrier to entry created by the Commercial Drivers License (CDL) requirement, and a training period that can last as long as 12 weeks.

The service also notes that many drivers have simply retired in response to the pandemic, while others left for positions in other industries after being affected by the impact of extended school closures combined with driver shortages in other markets.

In a press briefing the same day, Gov. Baker said the shortage wasn’t caused by a lack of vehicle hardware, but by a lack of professionals who have a CDL, an accreditation National Guard members have.

Baker also said the federal government will pay for the Guardsmen because the expenditure is classified as a COVID-related issue.

The trend is neither new nor isolated to Massachusetts. In August, Pittsburgh Public Schools District sought to postpone the opening day of classes by two weeks because of a 6,000 seat shortage.

In Chicago, 73 drivers quit the night before the first day of classes after Chicago Public Schools (CPS) imposed an Oct. 15 vaccination requirement on drivers. In response, the district distributed $1,000 up front followed by an additional $500 per month to parents to cover Lyfts or Ubers, according to Business Insider.

While that sum may seem sizable, one parent told a CBS affiliate in Chicago she paid Lyft $36 to drive her son, a special needs student, nine miles when no bus was available to return him home after she dropped him off the same morning.

CPS confirmed in a statement that “the rush of resignations was likely driven by the vaccination requirements.”

In Delaware, one charter district is paying parents $700 per child, per year, to take transportation into their own hands.

According to CBS News, the shortage is turning into a bonanza for potential drivers, citing $1,000 signing bonuses for drivers in Vermont, $3,000 signing bonuses in Connecticut, and a $27 per hour wage in addition to a $2,000 signing bonus in New York.

The outlet says the average national wage for drivers is only $16 per hour.

In a Sept. 2 statement issued by the Boston School Bus Drivers’ Union, they said the bus company had dumped 100 additional routes that weren’t present the year prior on the drivers at the last moment

“We’ve heard of no additional schools nor an increase in the student population,” said the Union.

“It would appear that it was the result of mismanagement and incompetent routing. By their own admission at the table today, they routed children who did not require transportation, some who have graduated, some who have moved.”

The Union also alleged that the City of Boston “has contracted with additional bus companies for some number of public charter schools in violation of their agreement with our Union.”

In August, research published by the New York Times in conjunction with Stanford University found kindergarten enrollment was down by more than 340,000 students in the 33 states examined. The data found schools in lower income communities or that imposed heavy pandemic measures on students had a greater decrease in enrollments.

For Massachusetts, a March article by the Foundation for Economic Education found, using U.S. Census data, that homeschooling stats skyrocketed in the state, going from 1.5 percent in the spring of 2020 to 12.1 percent by the fall.