Arguments are uncomfortable for many people — so much so that we may go out of our way to avoid certain topics; but there are times when an argument is necessary, and, if approached correctly, can be very productive. Poor arguments can lead to bad feelings all around, while a good argument is an opportunity for personal growth that can even help you strengthen relationships.

Arguments can be complicated and painful. Because they challenge our beliefs, it can be difficult to maintain an open mind; yet that is a critical part of good arguing. There are many pitfalls that can derail an argument, but exercising the universal virtues of truthfulness, compassion and tolerance will benefit everyone involved.

Let’s look at the key factors in an argument and how you can steer it in the right direction.

Why do we argue?

Human beings of different backgrounds and living in different circumstances are naturally going to have differing views. Our social nature dictates that we will interact and exchange these views, which will inevitably sometimes oppose those of our interlocutor. In this case, if either party feels strongly about the topic, he may choose to challenge the others’ beliefs with a set of reasons — an argument — why the other person should see things the way he does.

Should the other person choose to engage in the exchange and attempt to convince the instigator of his own views, an argument ensues. This can easily result in an angry debate where nothing is achieved other than hard feelings. When strong emotions are involved, people get offended, feel like they are being attacked, or even become hostile and irrational.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

While many people argue with the intention of “winning,” arguments don’t need to be competitive. You may wish to change another’s mind about something, but making them feel bad is the least likely way to be successful. An argument is successful when you come to an agreement — not when you dominate with your view.

Ideally, each party would enter an argument with an open mind — being willing to both give and receive new information. The intention should be to arrive at a closer understanding of the truth, or the best possible approach to solving the problem at hand.

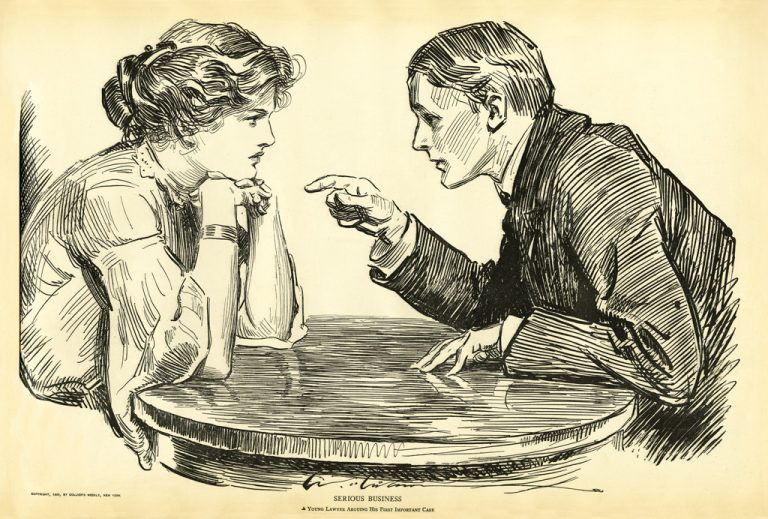

In promoting your own views, you are taking the role of a teacher. To be effective, you need to motivate interest in your subject, present your position in a way that is clear and rational, and show how it is beneficial to understand things this way.

Arguing well is a valuable skill that requires careful consideration and empathy. Few people are naturally adept at constructive arguing, but one who is can take the lead in promoting mutual understanding and preventing emotional clashes.

When is an argument necessary and useful

Before you engage in an argument, consider whether it is worth the trouble. Some people just like to push others’ buttons for their own amusement, while others may be hostile or aggressive, and unwilling to accept another viewpoint. It is rarely productive to engage in this type of argument. You can hold your head high without stooping to fight with a troll.

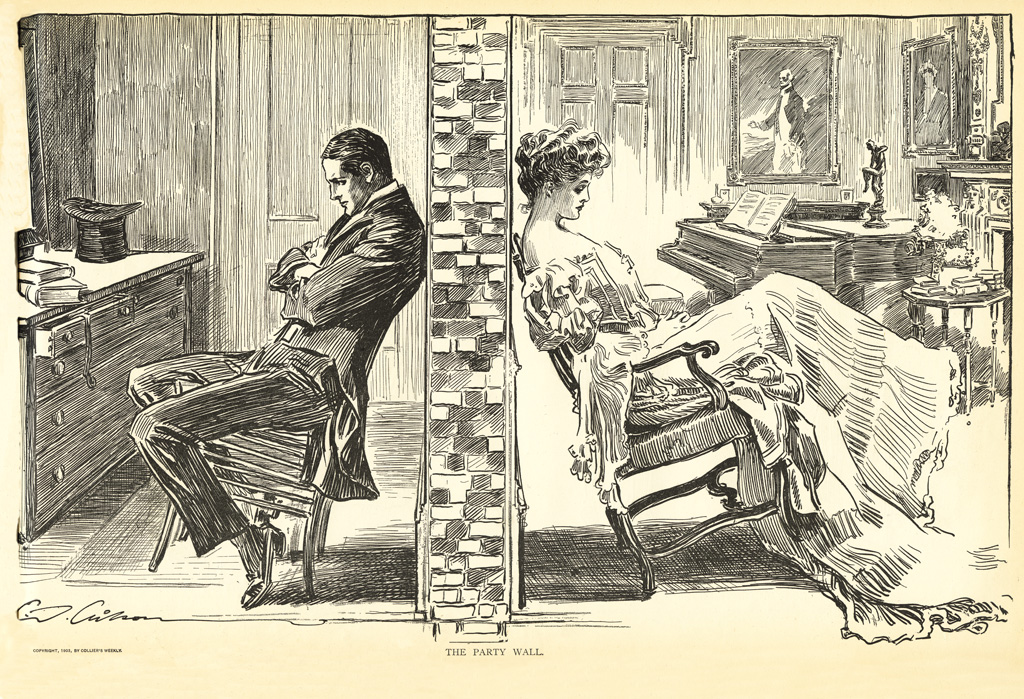

Other times, an argument may cause more harm than good. If the issue in question is of little importance; if the other person is extra-sensitive about the topic; or if you already know that the person is immobile in his views, it may be better to let it be.

Exchanges about important issues, however — like those that affect you and your family, or how to arrive at the optimal outcome — are critical for maintaining healthy relationships and moving forward. These, too, can be challenging; but with a little preparation and practice, you can make sure all your arguments are constructive and productive.

How to keep an argument constructive

In order to keep an argument from deteriorating, you need to be attuned to your partner-in-discussion. While you may not agree with them, you should be able to appreciate their position. Training yourself in a few key elements of empathy can make a huge difference in all your arguments.

Approach the argument with compassion

Remember that, just as you arrived at your beliefs through the interpretation of your own education and experience, your fellow arguer has gone through the same process to determine their own beliefs as valid.

As beliefs gradually develop through the course of life, they are typically reinforced with like notions that are easy to accept, until they become quite solid — like a big block of ice. Short of smashing the ice with force, the only way to change it is with warmth.

If you want to influence another person’s beliefs, you must show that you understand and respect them, by listening to their argument. After all, you can hardly expect others to be open to your views if you are closed to theirs. Allow that some of their reasoning is valid before pointing out what’s not.

Anticipate an emotional response

Being told that your reasoning is faulty never feels good. Be sensitive to your fellow arguer. Watch for signs of agitation and back off a bit if they are visibly upset. Some arguments are better taken step by step, allowing each party to process information and emotions in between.

You might experience agitation, frustration, or anger yourself. Be sure to remain rational and keep these emotions from influencing your argument. Remember that personal growth requires stepping outside your comfort zone, and that pushing through the pain will help you realize your goals.

READ ALSO:

- Improve Your Emotional Intelligence to Master Important Social Skills

- Transcending Pain: Understand, Accept, and Become Comfortable With Discomfort

- Calming the Control Freak in You

Be prepared

A serious argument isn’t something to enter rashly. In addition to a clear understanding of your own view and valid reasons for it, you should become familiar with the other party’s position before arguing against it. If you have a good grasp on how they think, you will be able to judge what sort of evidence they may be willing to accept.

You will also want to watch out for faulty reasoning, which can present itself in many ways. One instance is the “straw man” fallacy, where the opponent addresses a misinterpretation of the argument to avoid addressing the argument itself. This is a form of manipulation often used in politics.

Arguers may also grasp at anecdotes as evidence, rather than citing concrete data. While such singular cases may help illustrate a point, they rarely represent a universal truth. Do your homework and gather documented statistics or other reliable evidence to support your argument.

Other faulty reasoning includes “ad hominem abusive,” which attacks a person’s character as a reason to dismiss his opinion as invalid; and “begging the question,” which offers evidence that assumes one already agrees.

Once you’ve learned to recognize faulty reasoning, you can keep the argument on track by avoiding such tactics yourself, and pointing them out when you see them. Be sure to explain your assessment, lest it become an argument about arguing.

Play fair

A noble arguer will promote trust and mutual respect, setting the stage for rational reasoning. While a cunning debater may be successful, winning an argument by deception is no victory. Not only does it deplete one’s own virtue, it can also cause serious harm to others.

One need not look too far back in history for demonstrations of political leaders manipulating the masses with faulty reasoning. The Chinese Communist Party has made an art of it, with its many groundless persecutions over the years.

Take a high moral ground when arguing, and be responsible for what you say. Should you find in the process that your own reasoning was faulty, rejoice in the discovery that has helped you move closer to the truth.

“The one who loses in a philosophical dispute gains more the more he learns”

Epicurus