In China’s northwest, on the edge of the Gobi Desert, lies a town that was once a blessed stopover for the weary Silk Road traveler: the city of Dunhuang.

Surrounded by majestic sand dunes that give out a singing or drumming sound when the wind blows — hence their alternate name Singing Sand Dunes (Ming Sha Shan 鳴沙山) — Dunhuang sits in a historic oasis that continues to be a must-see for countless travelers each year.

Yet the awe-inspiring scenery is not the only worthwhile reason to visit this remote destination. Fifteen miles southeast of the center of Dunhuang lie the Mogao Caves, one of the most remarkable collections of Buddhist art in the world.

The Mogao Caves comprise a system of 735 caves containing the finest examples of Buddhist paintings and statues. More than 1,000 years old, these caves were initially excavated as places of Buddhist meditation and worship, and later became a place of pilgrimage for devotees, artists and officials.

READ MORE

- Gongshi: The ‘Scholar’s Rocks’ of China

- Tai Chi: The Daoist Martial Art of Winning Without Fighting

- Benefits of Sitting and Meditation in the Lotus Position

Faithful depictions of heavenly scenes

The ancient Chinese believed that deities appeared to the faithful in visions. Thus, it is thought that the breathtaking representations of heavenly beings and celestial paradises on the ceilings and walls of the caves, are nothing but accurate depictions of what the artists were allowed to see.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

According to the legend, a Buddhist monk named Le Zun (樂尊), adept in painting and sculpture, decided to take a break from his long journey to the Western Paradise. After drinking from the sweet waters of a nearby spring, he sat down to rest and contemplated the vibrant colors of the sky as the sun was preparing to set.

Suddenly, the mountains began to glow and a glorious golden Maitreya Buddha appeared floating in the sky. Then, the monk saw a myriad of Buddhas emerge, accompanied by heavenly fairies that were filling the air with angelic musical notes.

Moved by the celestial visage, the monk decided to make use of his artistic skills and portray what his eyes had witnessed. With a heart full of respect and a soul full of gratitude, Le Zun put all his human efforts into capturing the solemnity of the occasion.

Some years later, another Buddhist monk named Fa Liang (法良) visited the same place and had a vision identical to the scenes depicted in the first paintings of the cave. Feeling humbled and inspired, the monk painted his vision on a second cave and filled it with statues to honor the heavenly beings he caught glimpses of.

Over time, the caves became a religious and cultural destination, where countless artists and Buddhists found their own spiritual oasis. In the years that followed, the caves were filled with even more works of art, making the Mogao Caves one of the greatest sculptural sites in China, home to some of the finest examples of Tang Dynasty art, including murals and artifacts.

Detailed murals

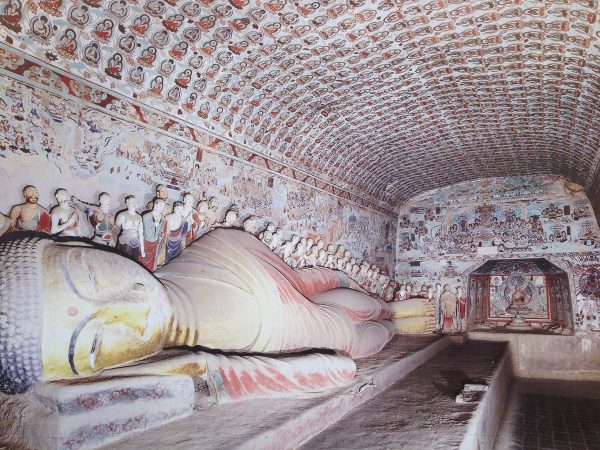

The murals in the Mogao caves are as extensive as they are rich in content and refined in technique. The paintings cover a total area of 490,000 square feet — or 46,000 square meters — with the most elaborate caves having murals on their walls and ceilings. The spaces that are not taken by figurative images are filled with geometrical patterns and plant decorations.

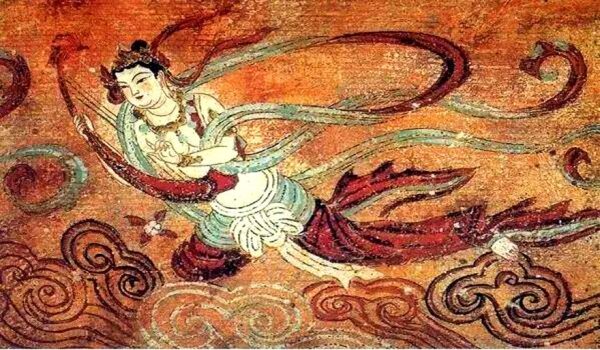

In most compositions, the central figure is that of a Buddha surrounded by other deities and heavenly beings. It is common to see flying apsaras or fei tian (飛天) — celestial beauties — on the ceilings or above the Buddhas, as well as narrative paintings depicting stories of the life of Buddha.

Another common theme in many caves is the large areas covered by rows of countless Buddhas seated in lotus position. With each seated Buddha nearly identical to the next, the fascinating motif not only gives the site the appropriate name “Caves of a Thousand Buddhas,” but reminds the viewer of the belief that through the Buddha’s benevolent mercy, anyone can attain enlightenment and be saved.

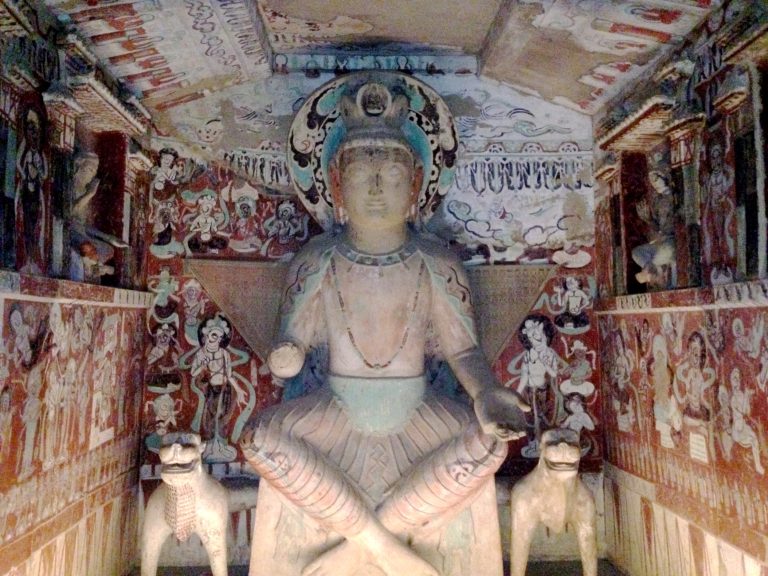

Mesmerizing sculptures

Today, the Mogao caves of Dunhuang are home to some 2,400 preserved clay sculptures. As in many wall depictions, Buddha statues appear as the centerpiece, assisted by bodhisattvas, celestial kings, fairies and mythical figures.

Two giant statues make Mogao a place like no other. Representing Maitreya Buddha — the future Buddha that will come to the world and reinstate the Dharma at the end of our times — these clay statues are among the largest in the world.

The larger one, located in cave 96, is over 100 feet tall — some 31 meters — and was built in 695 under Empress Wu Zetian, who is remembered for encouraging the construction of both monasteries and statues. The smaller statue is 88.5 feet tall and was constructed between 713 and 741.

Sacred Caves

The Mogao caves were dug into the side of a cliff. During the Tang Dynasty, a time of cultural heyday, the site had more than a thousand caves, but over time, many of them were neglected or lost, decreasing the number to the 735 caves we can see today.

The caves located in the southern region of the cliff are the most popular and frequently visited for pilgrimage or worship. Their northern counterparts, mostly devoid of decoration, served mainly as dwellings, meditation chambers and burial places for monks.

Each of Mogao’s caves was painstakingly carved by hand into the alluvial conglomerate rock cliffs. Their construction was often sponsored by monks, officials or affluent believers who wished to accumulate good karma and perform an act of respect and veneration.

Most caves are clustered according to their era, with each new dynasty having built their own set of caves in different parts of the cliff. Although these caves fell into oblivion after the decline of the Silk Road, they were rediscovered hundreds of years later, when a Daoist monk appointed himself guardian of the caves.

Today, many of the unparalleled works of art are remarkably well preserved, reminding us not only of the high artistic level of our ancestors, but also of the spiritual civilization that once existed in the land of China.