If any verses of ancient Chinese poetry continue to uplift the spirit and impress the intellect of today’s people, as much as it did for readers of the past, it is those of Li Bai (李白).

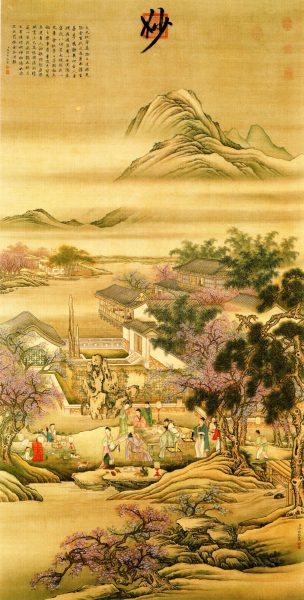

Often regarded as the greatest Chinese poet of all time, Li Bai’s work was among the most prominent during the Tang Dynasty — often called the Golden Age of Chinese Poetry — at a time in which even the emperor actively promoted and participated in the arts.

But what made Li’s poetry so distinctive and unparalleled? Some say it was his effortless mastery of the most complex verse forms that earned him timeless renown. Li Bai is often compared with his contemporary, the great writer Du Fu (杜甫), but whereas the latter was concerned with conveying strong social and moral themes in his work, Li focused on a more naturalistic style of depiction.

Others claim that it was the themes and content of his poems — laden with fantastic imagery and allusions to profound sentiments — that made his verses so unusually intimate for the reader but universal to the human condition.

Whether it was one of these reasons or a combination of both, one thing is certain. Li’s poems embodied one of the noblest aspirations that was common to all artists and scholars in ancient China: the desire to become one with existence through the refinement of his craft.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

永結無情遊 (Let us join to roam beyond human cares)

相期邈雲漢 (And plan to meet far in the river of stars)

—”Drinking Alone by Moonlight”. Stephen Owen, trans.

《月下獨酌》

The prophesied birth of a ‘Great White Star’

It is said that when Li Bai’s mother was pregnant with him, she dreamt of a big white star descending from the sky as if expelled from the heavens. This provides suitable explanation for Li Bai’s courtesy name Tai Bai (太白), which literally means “Great White” — the ancient Chinese name for the planet Venus.

Other nicknames were given to Li Bai by virtue of his prolific poetic talent. When the scholar and Daoist He Zhinzhang (賀知章), himself a poet, saw the grace and effortless dignity with which Li Bai created verses, he bestowed upon him the nickname “Immortal Exiled from Heaven,” which also accorded with the falling light in Li Bai’s mother’s dream. “The Poet Saint” and the “Immortal Poet” were other common nicknames given to Li Bai.

A curious child and wandering spirit

Born into a family where reading the “Hundred Authors” was a family literary tradition, young Li Bai was able to compose poetry before he was ten years old. He read extensively and particularly enjoyed Confucian classics such as The Classic of Poetry (詩經) and the Classic of History (書經).

Li also read astrological and metaphysical works that the literati of the time tended to eschew, and although his mastery of the subjects was remarkable, he was never interested in taking a formal exam.

In his early years, Li Bai engaged in humble activities such as fencing and taming wild birds. In time, he became fond of both swordsmanship and travel, which led him to praise knight-errant swordsmen, to whom he dedicated his poem “Ode to Gallantry” (Xiá Kè Xíng 俠客行):

銀鞍照白馬 (The silver saddle shines on the white horse)

颯沓如流星 (The valleys are like shooting stars)

十步殺一人 (One man is killed at ten paces)

千裏不留行 (A thousand miles are not left behind)

—”Ode to Gallantry”

《俠客行》

Guided by his insatiable desire to learn from other sages, Li Bai embarked on great journeys across China that brought him into the company of Daoists, literati and high officials who not only developed great admiration for the gifted poet, but also imparted their teachings to him.

五嶽尋仙不辭遠 (Searching for immortals in the Five Mountains)

一生好入名山遊 (A life devoted to travelling the famous peaks)

—”Ballad of Mount Lushan to Squire Lu’s Void Boat”

《庐山谣寄卢侍御虚舟》

This was the case with the legendary hermit Zhao (Zhào chǔshì 趙處士) under whose instruction Li Bai became a proficient swordsman of a high level of skill. Although Li Bai never fought for his country or obtained military honors, he left behind delightful verses praising the sword:

安得倚天劍 (And got to lean on the heavenly sword)

跨海斬長鯨 (Cutting the Long Whale Across the Sea)

and

願將腰下劍 (I would like to put my sword under my waist)

直為斬樓蘭 (Straight to cut down the Lou Lan)

—”Song of the King of Linjiang Festival” by Li Bai

《临江王节士歌》

Rapt with wine

Chinese author John Ching Hsiung Wu, sensibly noted that “while some may have drunk more wine than Li [Bai], no-one has written more poems about wine.” In fact, Li Bai’s love of wine was not only the subject of many of his prolific verses, it was often his source of inspiration.

長劍一杯酒 (With a longsword and a cup of wine)

男兒方寸心 (only then does a man have a heart)

—”Presenting a gift to Sir Cui” by Li Bai

《贈崔侍郎》

This was not a trait exclusive to Li Bai, but a pleasure enjoyed by many classical Chinese poets. Many great verses were composed while the writer was in a drunken state free of mundane concerns.

However, Li Bai’s love of drink would spell trouble for his career.

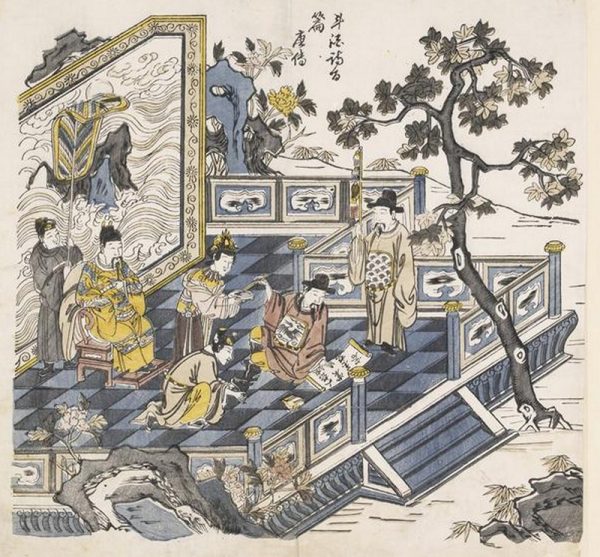

The story goes that one day, while serving as a scholar at the court of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (唐玄宗), the poet, overfueled by alcohol, insulted one of Xuanzong’s favorite eunuchs. The resentful eunuch, who was unfavorably disposed towards Li to begin with, soon found an opportunity to slander him before the powerful ruler. The emperor, despite his great admiration of Li Bai, was pressured to expel him from the imperial palace.

On the other hand, Li Bai’s love for wine earned him recognition as one of the “Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup” (yǐnzhōng bāxiān 飲中八仙). Having all lived under the same dynastic rule and enjoyed wine to the same extent, these Tang poets are often referred to as deities (xiān 仙) not because they had an eternal earthly existence, but as a metaphor for the immortality of their verses.

處世若大夢 (We are lodged in this world as in a great dream)

胡爲勞其生 (Then why cause our lives so much stress?)

所以終日醉 (This is my reason to spend the day drunk)

頹然臥前楹 (And collapse, sprawled against the front pillar)

—”Rising Drunk on a Spring Day, Telling My Intent” by Li Bai

《春日醉起言志》

Unmatchable skills: Li Bai’s technical virtuosity

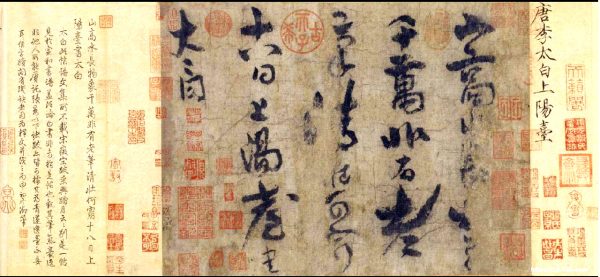

Li Bai was noted for his mastery of one of the most demanding verse forms of the time: lüshi (律詩). This was a classical Chinese poetry form consisting of eight lines, each composed of five, six or seven characters. The poet’s skill is demonstrated in lüshi forms by making the even-numbered lines rhyme, with the same rhyme being used throughout the poem.

Li Bai’s “Seeing Off a Friend” (Sòng yǒurén 送友人) is a well-known example of this form:

青山横北郭

白水遠束城

此地一為別

孤蓬萬里征

浮雲游子意

落日故人情

揮手自茲去

萧𦲸班慝嗚

Green hill across north wall

White water wind east city

This place is a farewell

A lonely canopy for ten thousand miles

Floating clouds and wanderers

The setting sun reflects my old friend’s feelings

Wave hand from this go

Neigh part horse call

—”Seeing Off a Friend” by Li Bai

《送友人》

Li Bai also excelled in the gushi (古詩) or “ancient verse” form and the jueju (絕句) or quatrain, the former being an older poetic form that allowed more freedom in form and content, and the latter with stricter requirements in terms of number of characters and alternation of tones.

The themes presented in Li Bai’s compositions range from praise of past glory to the pleasures of friendship and solitude, to the depths of nature and drunkenness. A student of Daoism himself, Li Bai often included fantastic imagery in his verses, stemming from his fascination with the several Daoist priests who practiced alchemy and austerities in the remote mountains of ancient China.

“Many of his poems deal with mountains, often descriptions of ascents that midway modulate into journeys of the imagination, passing from actual mountain scenery to visions of nature deities, immortals, and ‘jade maidens’ of Taoist lore,” said American sinologist Burtin Watson in describing Li Bai’s poetry.

And, like most Chinese poets, Li Bai also made room for nostalgic sentiments among his verses, often combining his heartfelt words with allusions to every poet’s faithful companion: the moon.

床前明月光 (Beside my bed a pool of light)

疑是地上霜 (Is it hoarfrost on the ground?)

舉頭望明月 (I lift my eyes and see the moon)

低頭思故鄉 (I lower my face and think of home.)

—”Quiet Night Thought” by Li Bai

《静夜思》

“Quiet Night Thought” is one of the most dearly remembered poems of Li Bai. Memorized by most Chinese schoolchildren and even read in other Asian nations such as Japan and Korea, it reminds today’s generations of the glorious but almost forgotten cultural legacy left by five thousand years of Chinese civilization.

READ ALSO:

- The Virtuous King Wen: Forging a Legacy for the Ages in an Era of Corruption

- Guan Hanqing–The Greatest Chinese Playwright

- The Scientific Accomplishments of Ancient China’s Guo Shoujing

- From Prisoner to Prime Minister: Guan Zhong and the Hegemony of Qi