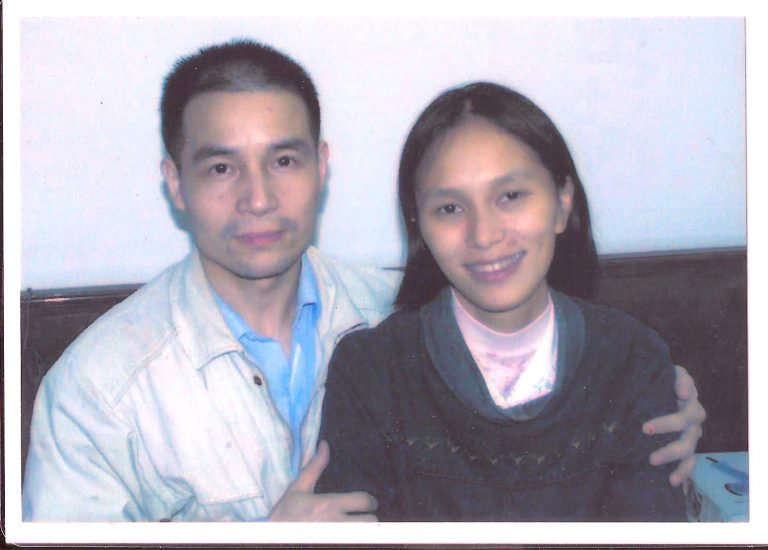

Yinghua Chen is a Chinese persecution survivor who immigrated to Calgary, Canada four years ago. During her time in China, she was arbitrarily imprisoned three times, forcibly separated from her family, and subjected to torture and harsh force-feeding sessions, all for refusing to give up her faith in Falun Gong — the meditative discipline that has been severely persecuted by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for the last 24 years.

But in a dark twist, her husband, Wen Yu, who received help from U.S. congressmen in 2016 to pressure the Chinese government to release her, is behind bars in Washington’s Thurston County Jail due to a lawsuit filed by another Chinese national in the United States.

Chen, who relayed her family’s story to Vision Times in a recent interview, believes her husband’s detention is a case of transnational repression by the Chinese Communist Party.

Life under surveillance

Chen was first detained on Aug. 8, 2003, for possessing CDs that exposed the communist regime’s disinformation about Falun Gong. She was held in prison, where repeated force-feeding caused severe bleeding in her stomach. About a month later, she was released on health grounds and was reunited with her husband.

The CCP had begun its persecution of Falun Gong on July 20, 1999. Acting on orders from then-regime head Jiang Zemin, China’s police forces arrested tens of thousands of Falun Gong practitioners throughout the country, while state media saturated the airwaves with propaganda defaming the Buddhist-school meditative practice.

- Retired Chinese Doctor Recounts Live Organ Harvesting in Military Hospital: Exclusive Interview

- Congress’s CECC Condemns the CCP’s 24-Year Persecution of Falun Gong, Demands Release of Detainees

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Just the year prior, Chinese authorities had been lauding Falun Gong: a study commissioned by retired Politburo member Qiao Shi concluded that the practice — first publicly taught by Master Li Hongzhi in 1992 — brought “hundreds of benefits and no harm” to society. The China’s National Sports Commission estimated that 70 to 100 million people, or roughly 10 percent of China’s population, had taken up Falun Gong, with most being attracted to the practice for the health and moral improvement they found in Li’s teachings.

Yinghua did not initially practice Falun Gong, but decided to do so after seeing the determination of her mother and other practitioners who braved arrest, torture, or worse to speak out in hopes the Chinese government would redress the matter.

With his wife back at home and her faith being targeted, Wen Yu and his parents — who lived in the same city — began to be monitored and harassed. Unable to bear the pressure, Chen’s in-laws advised her to move to her parents in Jiangsu Province.

At her parents’ home, where Chen gave birth to her son, Guo Yu, on July 30, 2004, local police began to intimidate her and her mother. Chen says she realized that the best way to protect her family was to stay away from them, so she sent her son to live with his paternal grandparents in Zhejiang and began traveling to other cities in China to help other Falun Gong adherents resist the persecution.

Shortly thereafter, her mother, who had just served a one-year sentence in a labor camp for her belief in Falun Gong, moved to Canada and was reunited with her husband and son, who had moved there a few years earlier.

As for Chen’s husband, she says he was under constant surveillance. “Our house was ransacked several times, and when he went out, he often saw cars following him,” Chen said. “He took note of the license plate of a car that followed him to a friend’s funeral. Days later, he saw the same car while walking down the street.”

Wen Yu’s income at stake

In 2006, Yu moved to Shanghai for work. There, he found a place to rent. With a stable job and a relatively good income, Yu was able to support his son and elderly parents.

Chen was reunited with her husband and began living with him in Shanghai, but she says she had to leave after six months due to police harassment. “A few months later, he was evicted from that place, even though the lease had been signed for one year,” Chen recounted. “The landlord told my husband that he had received threats not to rent to him.”

Yu returned to his home province of Zhejiang, where he found another job at a Microsoft branch in the city of Jiaxing. “They hired him quickly because they saw his skills and wanted to keep him,” Chen recounts. “However, in about a week, they fired him. The same pattern was repeated later with another job.”

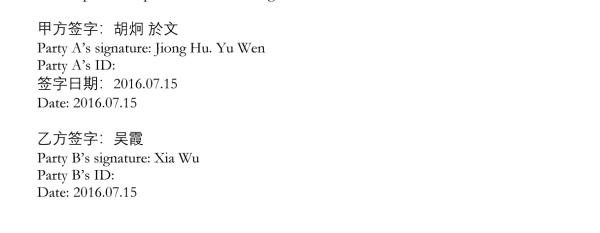

According to written accounts by Yu, he had been working on and off in partnership with a man named Jiong Hu for more than 20 years. Chen says her husband kept his earnings at Hu’s place in case the police ransacked his home.

In 2011, Yu learned that Hu had suddenly dissolved their company and refused to give him his share. All requests to recover his earnings were unsuccessful. Discouraged, Yu began to consider going abroad.

“When we talked, he told me, ‘We can’t live like this in China,'” Chen recalled. Wen Yu applied for a U.S. visa, which he received in February 2014.

On March 12, 2014, Chen was arrested for the third time in Shijiazhuang, capital of Hebei, to serve a four-year sentence. “He knew there was little he could do in China to help me,” said Chen. Yu hurried to the United States to seek help on May 8, 2014, and applied for asylum on June 16, 2014.

Seeking international support

After his arrival in the United States, Chen’s husband contacted government officials to ask for support in rescuing his wife. On June 20, 2016, six members of Congress wrote a joint letter to Chinese leader Xi Jinping expressing concern for Chen and six other imprisoned Falun Gong practitioners who were relatives of Washington state residents.

On March 12, 2018, Chen Yinghua finished her four-year prison sentence. Before letting her go, prison guards tried to force her to sign an agreement.

“They wanted me to promise three things: one, that after leaving prison, I would not get involved in Falun Gong activities. Two, that my family would not reach out to Western government officials, and three, that I would not accept any media exposure about Falun Gong,” said Chen. “Of course, I refused.”

Chen said the authorities tried to force her to sign the agreement on two more occasions, to the point of making it a requirement for her to obtain a passport, but she always refused.

A few months later, Chen received her passport, and on Oct. 21, 2019, she caught a flight to Calgary, Canada.

“Before I left, the Ministry of State Security [China’s intelligence agency] told me I was leaving the country through legal procedures, so I could come back as long as I didn’t say reckless things,” Chen recounts. “But they told me things were going to be different for my husband. I didn’t know what they meant.”

A suspicious reappearance

Shortly after the joint letter to Xi Jinping was made public, Jiong Hu, Yu’s former business partner in China, visited him in Washington.

“He wanted to resume his partnership with my husband and told him that it was the Chinese police that forced him to shut down their joint venture and withhold his share,” Chen said. “He paid my husband back and registered YuHu Lab in Washington state as their partnership.”

But Chen believes her husband was set up by CCP agents.

“It was only a shell company,” Chen said. “No real business dealings ever took place.”

Hu told Chen’s husband that he wanted to introduce him to a man named Bingfang Tu, who was interested in investing in their company. However, when they met, Tu did not discuss business but political matters, Chen alleged.

“He told my husband that it was useless to seek help in the U.S.,” Chen recounted. “He said that I, his wife, was still in their hands, and that they knew that his parents and siblings were still in China.”

“My husband stopped talking to Tu and never saw him again,” Chen said.

While the persecution of Falun Gong is concentrated in mainland China, the Communist Party also targets practitioners abroad. The 610 Office, a CCP organization established in 1999 to direct the anti-Falun Gong campaign, ran a network of overseas agents, some of whom were operating in the U.S. and Canada.

This August, the Department of Justice unveiled a case in which two individuals tried to bribe the IRS so as to have them rescind the tax-exempt status of an entity run by Falun Gong practitioners in the U.S. The accused were a naturalized American citizen from China and a Chinese national.

- The Lies That the Communist Party Used to Start 2 Decades of Persecution

- Man Who Attacked Falun Gong in Flushing Arrested, Charged With Hate Crime

Though the 610 Office was disbanded between 2018 and 2019, its mission and functions were taken over by other Chinese police units.

In addition to targeting Falun Gong, the CCP also harasses, threatens, or abducts individuals outside of China such as officials who fled the country to escape corruption charges or for other reasons, as well as political dissidents and members of China’s persecuted religious and ethnic groups.

The Party is known to maintain scores of clandestine police stations abroad, as revealed in a number of recent high-profile busts, including in Manhattan and Canada.

Inconsistencies in YuHu’s investment contract

Chen spoke about inconsistencies in the paperwork surrounding the case that she believes show her husband is the victim of deliberate fraud by his Chinese business partners — principally forgery of documents and signatures.

However, due to the language barrier and Yu’s lack of legal preparation, he was ill-equipped to handle the lawsuits coming his way.

- As China’s Finances Worsen, Thug-like Local Governments Impose a ‘Fines Economy’

- Family of Washington-based Student Activist Targeted By Chinese Authorities

A few months after meeting Bingfang Tu, Wen Yu learned that Hu and Tu had created an investment contract. “My husband had not signed any paper, but the investment contract contained [what was purported to be] his signature,” she said.

“The signature has strangely thick strokes, different from the other two signatures.”

Further, the signature in Part B [the investor] on the contract is not Tu’s, but that of a woman named Xia Wu, who is not mentioned elsewhere in the document.

Tu and Hu dissolve YuHu Laboratory–Wen’s name dismissed

According to a complaint document filed by Tu in 2019, he made investment transfers to YuHu lab between June 2016 and February 2017.

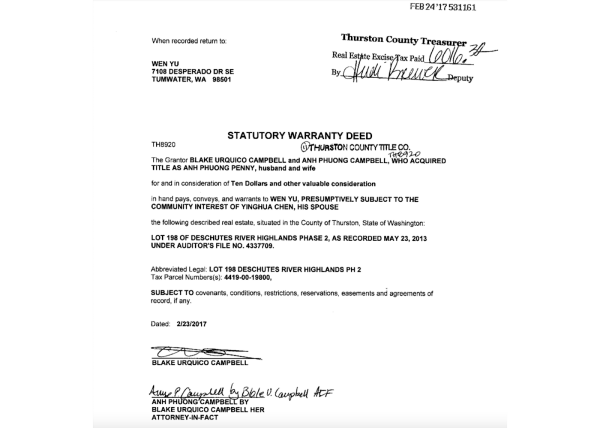

On or around Feb. 23, 2017, Wen Yu bought a house located at 7108 Desperado Drive SE in Tumwater, Thurston County. According to the same document, the property was purchased under Wen’s name at $337,715.

Tu’s document also stated that YuHu Laboratory LLC became inactive and was administratively dissolved on Nov. 1, 2017.

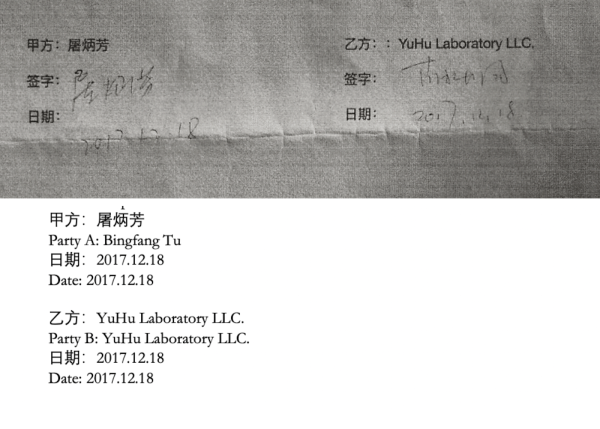

On Dec. 18, 2017, Tu and Hu signed a divestment agreement to dismantle YuHu Laboratory LLC. Without mention of Wen Yu, the agreement read: “Party B entrusts Jiong Hu to cooperate with Party A in this divestment.”

Tu claims Yu’s house

On April 30, 2019, Bingfang Tu, then residing in China’s Zhejiang Province, filed his complaint against Jiong Hu — also residing in China at the time — and Wen Yu, residing in Thurston County, U.S., before the Superior Court for the State of Washington for Thurston County.

In it, he set out the facts relating to his investment in YuHu lab, Wen’s purchase of a house and the dissolution of the company; and stated his intention to take possession of Wen Yu’s property — again by fraudulent arguments, Chen alleges.

“Tu was claiming that my husband had bought the house using his investment in YuHu Lab,” explained Chen. “[But] he bought the house with the funds that Hu owed and paid him, plus some funds forwarded by his parents.”

Under the “Facts” section of the complaint, Tu’s lawyers claimed that “No owner in the Real Property resides at the property as their primary residence and therefore the Homestead Exemption does not apply.”

“But [Wen Yu] always lived in that property and it was his private residence,” Chen said. “Also, accusation documents were all mailed to that address.”

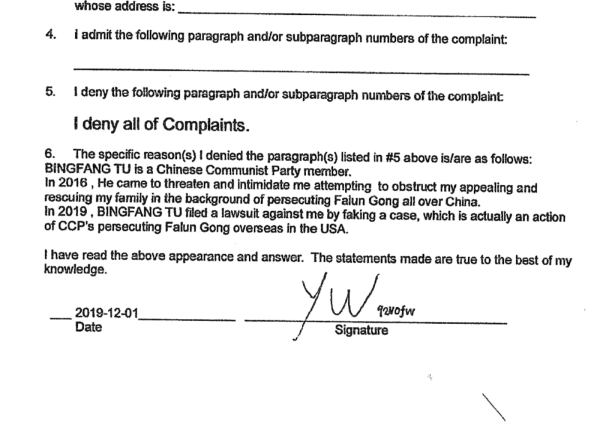

On Dec. 1, 2019, Wen Yu responded to the summons, denying the charges in their entirety.

Emergence of new evidence

On May 10, 2022, Tu’s lawyer filed an amendment to a Quiet Title Order they had signed due to the discovery of a Feb. 23, 2017 Statutory Warranty Deed that claimed that Yu’s property was subject to the community interest of Yinghua Chen, his wife.

But Tu’s lawyer claimed in the amendment document that Wen Yu was not married to Yinghua Chen, but to another Chinese woman called Ping Song, who was residing in the U.S.

“Plaintiff [Bingfang Tu] has located information showing that Wen Yu was married to Ping Song on March 21, 2008. Mr. Yu and Ms. Song formally separated on November 30, 2015 and a dissolution decree was filed on December 21, 2017 in Lincoln County Superior Court.”

“But my husband was not even in the U.S. in 2008,” said Chen, explaining why she thinks the allegations of Yu being married to another woman are false. “My husband only received his U.S. travel visa in 2014.”

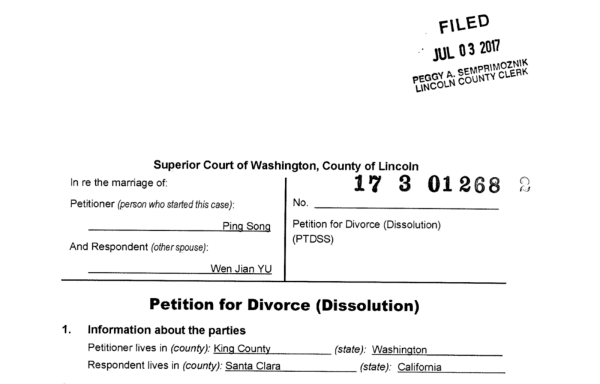

To support the allegations of a supposed divorce between Wen Yu and Ping Song, Tu’s lawyer provided a document containing a Petition for Divorce, filed on July 3, 2017.

The document notes that Ping Song was married to a man called Wen Jian YU.

“But the area that supposedly contains my husband’s name is wrong,” Chen said. “That is not his name. This is just another man with the same last name [Yu].”

Arrested

Despite what Chen and her family say are clear inconsistencies in the evidence and case details, the court sided with Hu and Tu, eventually resulting in Wen’s arrest — not in China, but on U.S. soil.

On Oct. 24, 2022, the court granted a Writ of Restitution to Bingfang Tu, commanding the Sheriff of Thurston County to deliver the property to Tu and arrest Yu if he did not evict the premises.

On Dec. 29, 2022, while Yu was speaking on the phone with his son — who had been rescued from China and brought to Canada with the help of Canadian government officials — police came to his residence. Tu’s lawyer, the Sheriff and TCSO Deputies had come to evict Wen, but he refused to come out.

According to Chen and Yu’s son, Guo Yu, who was on the phone during these events, he heard his father and the police yelling at each other. “I could hear shots fired over the phone, so I asked him about it. He said it was tear gas,” Guo stated in his written accounts.

After a SWAT intervention, Yu surrendered and was taken into custody.

Life in prison

According to Chen, Yu’s experience in prison has been difficult because of his limited English. She says that, to help her husband stay strong, she has tried to mail him a Chinese copy of Zhuan Falun — the main text containing the core teachings of Falun Gong — but he has been unable to receive it due to the prison not approving the publisher.

“On May 10 of this year [2023], I mailed two copies of ‘Zhuan Falun’ to my husband, one in Chinese and one in English,” said Chen. “Later, my husband received everything except the Chinese book Zhuan Falun. My husband asked for it many times, but the prison staff said they couldn’t find it.”

Chen said a Falun Gong practitioner in Seattle sent Yu another copy of the Chinese version on Oct. 18. “My husband said there was a record showing the book was received. But the prison administrator said it had been returned because ‘Publisher no longer authorized,’” she explained.

“He needs to gain the courage to persist in his beliefs,” said Chen.

Chen said she hopes people can recognize the case against her husband as an example of the CCP’s transnational repression — and that the U.S. justice system does not fail him.

While Chen says she does not have hard evidence to prove that Wen Yu was targeted by the CCP’s efforts to extend its persecution of Falun Gong overseas, she hopes that her husband’s case — and the inconsistencies she believes surround it — can help raise awareness about Beijing’s transnational repression.

The Party’s agents, she said, have no qualms about “using the U.S. judicial system to their advantage. This may escape the awareness of the kindhearted American prosecutors and judges.”

Editorial note: Due to the frequent reference to U.S. court documents, most Chinese names in this article have been given in Western-style order, i.e. given name first and family name second.