Perhaps the most well-known of the ancient Chinese sages, Confucius dedicated his life to reviving and transmitting timeless values to guide human conduct. He traveled the many states that made up the China of his age, hoping to harmonize families and society through morality and self-cultivation.

Though Confucius’ teachings often fell upon deaf ears — and were even suppressed — his wisdom was passed down by his thousands of disciples, and came to shape the culture of China and its neighbors.

Confucian ideas, including order between generations, proper family relations, and the Doctrine of the Mean, have remained the core of East Asian civilization for thousands of years, providing stability and community for these ancient societies.

Confucius himself was as much a learner as he was a teacher, remaining humble and open-minded throughout his days. His quest to mend the broken ways of the world was accompanied by a constant pursuit of spiritual elevation, which benefited from his brief but fateful encounters with Lao Zi, the legendary sage of Daoism.

READ MORE

- Jun Zi: Confucius’ Teachings on Being a Gentleman

- The Orchid Pavilion: A Celebration of Beauty in Poetry, Calligraphy, and Music

- Su Shi, the Ancient Poet Who Put the People First

A cherished son

Known respectfully in Chinese as Kong Fuzi (孔夫子) or simply Kong Zi, which means “Master Kong,” Confucius was born as Kong Qiu (孔丘) in the state of Lu, a part of today’s Shandong Province in eastern China. The name he is known by in the West — “Confucius” — is a Latin translation of the Chinese honorific.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

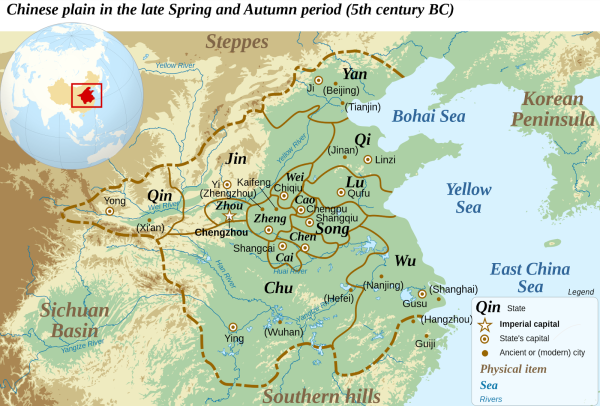

The age in which Confucius lived was one of rising strife and discord. He was born on Sept. 28, 551 B.C., at the end of the Spring and Autumn period (770–c. 481 B.C.). China was notionally governed by the kingdom of Zhou, but central authority had weakened to the point that the feudal states acted like independent countries, bickering and fighting amongst each other in pursuit of political hegemony.

Confucius did not come into the world easily. His father Kong He (孔紇), also called Shuliang He (叔梁紇), was 72 when he was born. Though the scholar and military officer already had nine children by his main wife Lady Shi, all were girls and could not continue Kong’s family line. He had a son, Kong Pi, by a concubine, but he was said to have deformed feet and thus ineligible to become his father’s heir.

As his last resort to produce an able-bodied son, the elderly Kong convinced the patriarch of the Yan family to allow him to marry one of his daughters (Lady Shi had passed away by this point, and a man could only have one main wife).

The youngest of the Yan family’s three daughters, Yan Zhengzai (顏徵在), became Kong He’s wife at the age of 18. Worried that she would not be able to conceive in time due to her husband’s age, Yan went to Mount Ni, praying to the mountain’s deity to bless her with a son. Her piety was rewarded, and she became pregnant with Kong Qiu.

The elder Kong died when Confucius was just three years old. His widowed mother raised him and Kong Pi — whose mother had also died — in harsh circumstances of poverty. As Yan had come from a well-educated family, she passed on to Confucius what she knew, sowing in him the first seeds of scholarly aspirations. However, she did not live to see the great man Confucius would become, for her life ended when she was 33 and her son, 17.

Kong Qiu saw to it that his mother was buried in his family’s ancestral grave, and set out on his mission to rectify the state of the world. The Spring and Autumn period was a time when various schools of thought competed for influence (百家爭鳴), with many great minds offering solutions for the disorder that reigned.

His own birth being a hard-won fortune for his old father and faithful mother, Kong Qiu valued the efforts of his parents. He believed that the root of all social harmony was harmony in the family, something could be achieved through xiao (孝), or filial piety.

Wandering the Zhou states

Confucius lamented the decline of the Zhou kingdom, which had functioned on an honorary system of mutual accord between the royal house and local nobles. He believed that the rthe kingdom’s troubles lay in the loss of moral conduct and ritual behavior that characterized the early period of Zhou rule.

He was keenly aware that moral conduct had to start with the individual’s demeanor, an important factor in which was filial piety. As Confucius would later tell one of his prominent disciples:

“To establish our characters and practice the Way, thus leaving our good name to future generations and glorifying our fathers and mothers, this is the ultimate achievement in filial piety.”

At the age of 19, Kong Qiu married Lady Qiguan (亓官氏). A son Kong Li (孔鯉) was followed by two daughters, one of whom is believed to have died as a child.

In feudal China, there were several castes. Confucius’ family belonged to that of the shi (士) or scholar-warrior, somewhat similar to the later samurai of Japan. The shi also served as government officials.

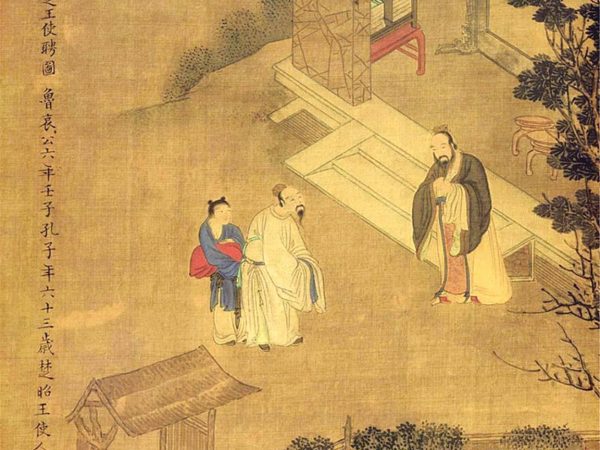

Like his father, Confucius became an official, having studied the Six Arts of rites, music, archery, chariotry, calligraphy, and mathematics. The young man held various government positions, but was disillusioned by the corruption of the Lu State nobility he served. Sometimes, the internecine conflicts left Kong Qiu and others in the shi class jobless.

However, as the feudal rulers sought prestige and power, they saw the value in keeping learned men by their sides. Mastery of aristocratic traditions could allow the regional lords to adopt the rituals of the Zhou court and other institutions, which apart from maintaining the vestiges of royal order was also useful in diplomacy and political intrigue.

Fed up with the dysfunction he saw in his homeland, Confucius eventually abandoned his posts and left Lu State, setting out on a journey across China to enrich his knowledge and promote his ideas.

Confucius sought audiences with regional rulers, hoping they would follow his moral advice. He also advocated universal education regardless of social class, believing that anyone with the right aptitude could benefit from instruction. Confucius would instruct thousands of students over the course of his life.

As Confucius gained a reputation and followers, many approved of his aims to restore the Zhou rites and the national polity that rested on honor rather than regulation, but doubted his odds of success.

For example, when a disciple of Confucius entered a city and made mention of his teacher, the local noble said, “that is the man who persists in doing what he himself knows cannot be done” (知其不可為而為之者).

Indeed, few of the nobles Confucius engaged were sincerely interested in restoring the values that had once brought the Zhou Dynasty strength and prosperity. In the decades after Confucius’ death, disputes between the feudal states would escalate and boil over into total war. The Warring States period would not end until the unification of China by the First Emperor in 221 B.C.

Still, Confucius stayed in good spirits and cherished the opportunities he had to impart knowledge and learn from others.

One famous line of his goes, “In a group of three people, I can surely find my teacher among them. I take what they do correctly and follow their example; I see what they do that is wrong, and correct that problem [in myself].”

Moral teachings for secular life

While the elites were lukewarm about Confucius’ teachings, many ordinary people found great value in his instruction. Confucius taught around 3,000 students.

Confucius believed that the goal of education was to produce virtuous individuals who would behave in accordance with traditional values and moral codes. Adhering to the ideal of the superior man who learns for the sake of learning and is righteous for the sake of righteousness, Confucius established a system of conduct guided by the principles of moral self-cultivation.

At the core of his teachings were the Three Fundamental Bonds and Five Constant Virtues (Sāngāng Wǔcháng 三綱五常). The philosopher explained that the three bonds between father and son, lord and servant, and husband and wife were the foundations of a harmonious society. However, the cultivation of such bonds depended largely on the refinement of each person’s character by following the five elemental virtues of benevolence (Rén 仁), righteousness (Yì 義), propriety (Lǐ 禮), wisdom (Zhì 智), and trustworthiness (Xìn 信).

Benevolence encompasses an altruistic sense of virtue. It implies fulfilling one’s responsibilities to others without regard for personal gain. In a broad sense, it is defined as humanity, empathy and understanding towards others. According to Confucius, benevolence is cultivated by embodying the basic virtues of seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence, and kindness.

Often translated as righteousness or duty, the virtue of Yi implies the ability to maintain virtue and justice under all circumstances. Encompassing qualities such as honor, loyalty and brotherhood, righteousness was a central concept in traditional Chinese culture.

Rituals and propriety are another cornerstone in Confucian thought. The philosopher believed that rituals and forms of propriety were the most effective method for people to reconcile their desires. By restraining one’s indecent nature and reinforcing one’s decorum, it was possible to demonstrate respect for others and adhere to proper social behavior.

Wisdom entailed the proper understanding and application of the other virtues as well as the ability to assess a person’s character in the proper light. The value of trust or faith, on the other hand, implied reliability, responsibility and the ability to commit, which was conducive to strong and harmonious interpersonal relationships.

Proper governance

For Confucius, ethics and morality were the foundations of good leadership. He was the first to privilege the attainment of skilled judgment over the knowledge of rules, explaining that good morals were more effective in regulating people’s behavior than laws. Confucius believed that the best way for a ruler to instill morality in his people was to become their moral exemplar himself.

“If the people be led by laws, and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of the shame, and moreover will become good.”

(Analects 2.3, tr. Legge).

Amidst the chaos and endless wars between feudal states, Confucius wanted to restore the Mandate of Heaven (天命) to unify the nation. Looking up to the tradition of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, the philosopher believed that a centralized government would be far more effective in bringing peace and prosperity to the people, as opposed to the eroding and ever-contending feudal system of his time.

Yet the ruler had to earn his power on the basis of his moral merits instead of lineage. Thus, the relationship between the ruler and his people would resemble that between a father and his son, with the ruler devoted to his people and the people respecting their superior and cooperating unconditionally.

Moreover, Confucius said, a truly effective government would place moral cultivation above even material necessities before concerning itself with the economy and defense.

A disciple asked him: “Suppose a country has to go without its army, food, or trust. Which should be given up first?”

The master replied, “Do away with the army first, then the food. No nation can survive in this world without trust.”

This sentiment was echoed in a conversation between Mencius, one of Confucius’s most famous students, and King Hui of Liang State. The king lamented his country’s loss of territory to its enemies, and sought to atone for his embarrassment before his ancestors.

Mencius noted that all the surrounding states burdened their people with severe taxation and punishments, leading to resentment and tragedy among the masses. “If Your Majesty implements benevolent policies among the populace,” he said, “the people will have opportunity to cultivate their filial piety and respect.” Such a society would not only be able to defend itself, but also vanquish corrupt rival states as a matter of course.

Along with its moral exhortations, Confucianism taught the Doctrine of the Mean (中庸). According to Confucius, “the virtue embodied in the Doctrine of the Mean is of the highest order. But it has long been rare among people.”

Also called the Middle Way, this idea was codified by Confucius’ grandson Kong Ji (孔伋). It holds that the way to peace in both familial or interpersonal relations and in politics was to avoid extremes. He who can balance all things well in life and society, without acting in excess, will enjoy longevity and prosperity.

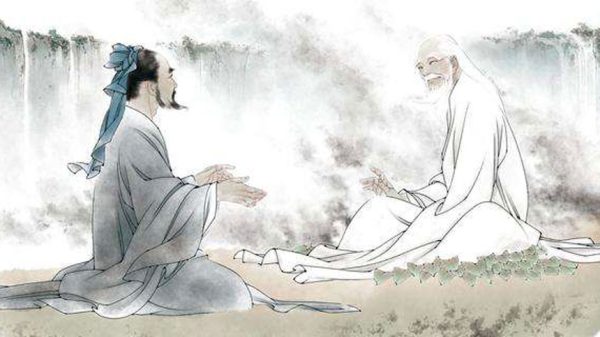

Learning the Dao

Confucius’ profound knowledge was shaped by his encounters with Lao Zi (老子), the Old Master of Daoism.

The first meeting occurred when Confucius, then in his thirties, visited the capital to learn the Zhou system of ceremonial observations from the venerable sage, who was then working as a historian in the royal archive. Confucius knew that only Lao Zi could reveal to him the source of ritual music and the essentials of morality.

After receiving instructions from Lao Zi and preparing to take his leave, Confucius expressed to the sage his greatest concern:

“I am worried that the Way is not working. Benevolence and righteousness are not practiced, war and chaos are endless, and the country is in turmoil.” He then manifested what was both his ultimate aim and major fear: “I sigh that life is short, and I cannot be useful to the world and to the people.”

Seeing Confucius’ intentions, Lao Zi proceeded to point out his student’s shortcomings in an effort to help him improve. He thus taught Confucius the virtues of water.

The sage explained that water embodies the virtue of modesty, since it benefits all things without competing. Being soft and weak, water resists nothing and adapts itself to everything. Flowing low and not chasing heights, water tames all grains and crops with its submissive nature.

Then he gave Confucius blunt advice: “You should get rid of your pride and desire, get rid of the attitude and the air, and get rid of those ambitions you are so passionate about, because these things are no good for you at all.”

Confucius thanked the sage for his benevolence, promising to keep these lessons in his heart. He then set out on his journey home.

Some 17 years later, Confucius learned that Lao Zi had returned to Pei from Song State to live in seclusion. He thus decided to pay him a visit.

Lao Zi greeted him cordially and prepared to listen. With a troubled heart, Confucius told the sage that he had not yet obtained the Dao, despite studying diligently and traveling great distances. Therefore, he had returned to seek advice.

The wise man said: “The Dao is as deep as the sea, as tall as a mountain, all over the world and everywhere. It flows incessantly and reaches everything. When you seek it, it is unattainable; when you discuss it, it is inaccessible! The Dao gave birth to Heaven and Earth without waning, and bore all things without withering. Because of the Dao, the sky is high, the earth is thick, the sun and the moon are in motion, the four seasons are in order, and all things take shape.”

He then expounded on how human conduct could align with the Dao. He explained that following the course of nature was the way of a sage, and that one who lets things happen naturally without clinging to things that change is a person who has attained the Way.

The unpretentious but profound words of the Old Master shook Confucius to the core: “At 15, I set my heart upon learning; at 30, I had planted my feet firmly on the ground; at 40, I was no longer perplexed. Now at 51, I have learned what creation is!”

Upon his return home, Confucius is famously said to have sat in silence with his disciples, before finally praising Lao Zi as akin a sublime dragon that could not be grasped nor comprehended.

He further devoted himself to teaching students, writing books and editing existing texts, leaving behind a philosophical system that would later be codified and taught generation after generation.

Confucianism throughout the ages

Confucius’ ideas were popular but did not go without opposition. The era in which Confucius lived was known as a time when “a hundred schools of thought contended” (百家爭鳴) for influence.

Some intellectuals, like the Mohists, preached the doctrine of “equal love” (兼愛) as opposed to the “universal love” (汎愛) spoken of by Confucius. Because Confucius taught that it was natural for people to love their family and friends more than outsiders, proponents of Mohism — the creed of engineer Mo Zi (墨子) — denounced Confucianism for not encouraging equality.

The real challenge to Confucian ideas was Legalism (法家), a totalitarian ideology which held that humans, being inherently selfish, must be governed by strict laws to enrich the country and strengthen the military. Legalist philosophers regarded independent philosophy and even moral teachings as dangerous sophistry that would “dismember” the country.

Kings of Chinese states were attracted to Legalism, which placed all power in the hands of the sovereign. Eventually, the land was unified by Ying Zheng, the king of Qin State, who founded China’s first imperial dynasty. Confucian books were burned along with the writings of the other schools of thought that once flourished throughout the country. Except for the Yi Jing (Book of Changes), used for divination, all other philosophical texts were banned. Only the dedicated efforts of a few scholars, who hid the teachings of the great master in lacquer furniture, allowed Confucius’ ideas to survive.

In 206 B.C., the Qin empire collapsed under the weight of its draconian laws soon after the First Emperor’s death. The following Han Dynasty took a laissez-faire Daoist approach to governance (黃老之治), encouraging a limited bureaucracy and economic growth.

Confucianism saw a revival during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Han. The emperor had struggled to rein in corrupt vested interests that had set in under his forefathers, and needed a new philosophy to guide the people and cement his rule.

Consulting the scholar Dong Zhongshu, Emperor Wu decided to establish Confucianism as the state ideology, declaring that only through virtuous rule could an emperor claim the Mandate of Heaven. Any monarch who went against divine will could — and must — be overthrown. Emperor Wu’s reign was one of the major golden ages in Chinese history.

In the Song Dynasty, scholars deliberated further on the inner meanings of Confucian teachings, leading to the creation of what is known in English as “neo-Confucianism” (理學) but perhaps more accurately rendered “study of principles” or simply “Rationalism.” While the philosophers of neo-Confucianism sought to bridge the sage’s wisdom with that found in Daoism and Buddhism in search of philosophical truths, the new intellectual trend ended up being reduced to formality.

The content of imperial exams became increasingly arcane and cryptic for the purpose of filtering out almost all aspiring scholars from the elite class, while vapid or extreme interpretations of Confucian doctrine became mainstream.

The imperial system and Confucianism remained in place for 2,000 years until the abdication of the last emperor in 1911. Confucian thought transcended the boundaries of space and time, exerting a remarkable influence on East Asian culture and remaining influential to this day.

Confucius himself was honored as the “exemplary teacher of all generations” (萬世師表), and his descendants were granted honorary noble titles in each dynasty. Today, his 79th-generation grandson, Kong Tsui-chang, holds the Republic of China honorary government title of Ceremonial Official to Confucius (大成至聖先師奉祀官) in Taiwan.

Abused–and misused–by the Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has long criticized Confucius in its crusade against the “evil old society” of ancient China, but has infamously appropriated his name to boost nationalism at home and spread its propaganda narratives abroad.

At the core of the Communist’s Party ideology are the ideas of atheism and materialism, rooted in the Marxist philosophy of struggle. After seizing power in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) turned against traditional culture and faith, labeling it as “feudal superstition.” Confucius, one of the greatest representatives of traditional culture, was denounced as “regressive, pedant and feudal” by Mao Zedong, the founder of the communist “New China.”

During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the Red Guards acted on Mao’s instructions to purge the “four olds” — old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits.

The temple of Confucius in his hometown of Qufu was destroyed and his cemetery vandalized. In an ultimate insult to the teacher, the remains of several descendants were exhumed, desecrated, and burned.

The moral teachings of the philosopher were replaced by the secular cult of the Communist Party. Through intense campaigns, the CCP forced the masses to believe that the destruction of ancient culture was tantamount to saving people from living in an antiquated and backward past.

Thus values such as filial piety and living in harmony were rejected and acted against to the extremes. Children were encouraged to denounce their parents if they did not agree with the party, and the cult of money and loyalty to the party became the basic values of society.

In recent years, the CCP announced it would blend Confucian teachings into its socialist ideology to make the Chinese nation more confident of its own culture and counter the impact of other cultures. To this end, the Party has deliberately removed what it refers to as the “unenlightened and feudal parts” of Confucianism, and appropriated a narrowly defined selection of Confucian ideas.

The idea of harmony is a telling case. According to the ancient sage, a harmonious society is that in which each individual fulfills his responsibility in a moral way. However, according to the Party, a harmonious society is one in which there is no dissent for communist rule, which in turn justifies its arbitrary suppression of minorities and prisoners of conscience.

READ ALSO:

- 77th-Generation Descendant of Confucius Dies in Beijing

- China’s New AI ‘Prosecutor’ Can Charge People for Political Dissent

- Confucius Institutes Rebrand on Canadian Soil Under New Name

Confucius’ idea of obedience and respect to superiors has also been employed by the CCP to demand loyalty and support to its authoritarian rule. By making it mandatory to join Party organizations such as the Communist Youth League or and Communist Young Pioneers, all Chinese citizens are required to swear a vow to dedicate their lives to serve under CCP rule. The Confucian precondition for the people to respect and cooperate unconditionally with their ruler, i.e., that the ruler prove himself to be a virtuous exemplar, was clearly discarded.

The CCP has also twisted Confucius’ words to present its atheist Marxism as ancient Chinese culture. Unlike spiritual practices, Confucianism concerns itself mostly with secular morality. Confucius himself said, “I respect the gods and spirits but keep a distance from them” — something that the Party’s propagandists have promoted to mean that Confucius did not believe in the divine.

But Confucius did not deny the existence of gods, and in fact said in his observations on filial piety that “when filial piety and fraternal respect are complete, they sync with divine grace, illuminating the four seas, leaving no place in darkness.”

In other words, Confucius, like other holy men, taught faith and virtue in the mortal realm are blessed with divine favor.

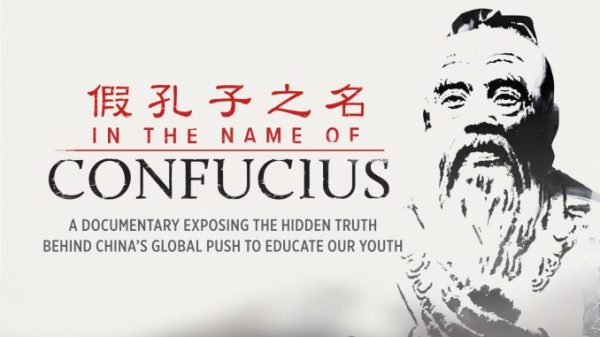

The CCP sees all faith and morality as roadblocks to its rule, or as useful political tools. Since 2004, China has opened over 1,600 Confucius Institutes and related Confucius Classrooms worldwide to promote the communist version of Chinese language, culture, and history.

Presented as a benign facilitation of cultural exchange, these institutions prohibit their professors from discussing topics that the CCP considers controversial, such as China-Taiwan relations, the ongoing violation of human rights or the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

A documentary, In the Name of Confucius, depicts how Sonia Zhao, a Falun Gong practitioner living in Canada, was barred from working as a Chinese teacher for the Confucius Institute at McMaster’s University because she refused to sign agreements saying that she would avoid discussion of her faith or the persecution it faces in China.

Fortunately, both policymakers and the public are gradually learning to see through many of Communist China’s means to influence and infiltrate the West. In the meantime, millions of people in China and abroad are rediscovering the beauty and wisdom of five millennia of traditional Chinese culture. Through visual arts, performing arts and the revival of spirituality, the world is being reminded of a truth about life and the universe that our ancestors clearly knew but that many have been forced to forget.